December 6, 2012, by Alan Sommerstein

From Mount Sinai to Michigan: the rediscovery of Menander’s Epitrepontes (part 4)

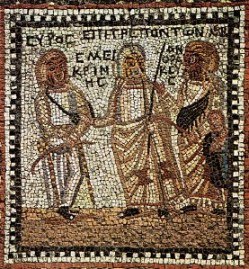

The ten new papyrus fragments of Menander’s Epitrepontes that have been published during the last forty years have added very considerably, but rather unevenly, to our knowledge of all five acts of the play. One contains small parts (never more than eight letters) of about 70 lines from Act One; not much can be understood, but some names of speakers are given in the margin. We can at least see that the opening scene was quite a long one, and we probably now know all the characters who appeared in it. Another new fragment handily fills most of the gap between what appears on the two sides of the St Petersburg leaf (with one of which it overlaps). A third gives us much of the run-up to the arbitration scene in Act Two, including part of a cantankerous monologue by Smikrines about his wayward son-in-law and the arrival of the two quarrelling slaves. A fourth slightly extends our knowledge of the end of the play. But most of the new fragments are clustered in the latter part of Act Three and the first part of Act Four. At this point Smikrines has discovered (so he thinks) that his son-in-law Charisios has fathered a child by the slave/musician/prostitute Habrotonon, and is naturally furious. He decides to exercise his legal right to terminate his daughter’s marriage and take her home with him. But at the start of Act Four we find him meeting unexpectedly stout resistance from the daughter, Pamphile, herself (who now comes on stage for the first time in the play): he tries to argue that she will have a wretched life having to share her husband with this “whore”, she insists that she came to Charisios to be “the partner of his life” and will not abandon him now – and eventually Smikrines gives up and leaves, probably declaring his intention to return with Pamphile’s old nurse in the hope that she will be able to persuade her mistress to see what Smikrines regards as sense. Pamphile is left distraught – until she accidentally meets Habrotonon with the baby, and recognizes it as her own child. So much we already knew, partly from a few lines surviving in the Cairo codex, partly from ancient quotations, partly from what Charisios says when he comes on stage for the first time in the play, having overheard much of the father-daughter argument from inside his friend’s front door. But now the new papyri – especially several fragments in the University of Michigan collection, all coming from the same badly damaged copy – have fleshed out many of what were once the bare bones of this part of the play.

We can now, for example, make sense of the last few lines of Act Three. When Smikrines goes in to speak to his daughter, Charisios’ friend, Chairestratos, is left alone on stage, and says that everything has gone wrong for him, but he must go and carry out a task which has been assigned to him. It can only be Charisios who has assigned him this task, and the one thing that Charisios needs to do at this stage – as Habrotonon had already foreseen – is, now that he believes her to be the mother of his child, to buy her from her owner so that he can set her free. And if this means that everything has gone wrong for Chairestratos, it must be, as many scholars had argued previously on other grounds, because he is himself in love with Habrotonon and must now renounce all hope of winning her. (Things will, of course, look very different for him once the truth is discovered and Charisios reunited with his wife.)

But most strikingly, we now have much more of the actual text of the argument between Smikrines and Pamphile. Three papyri preserve parts of the end of the father’s speech (which was probably about 85 lines long, all told) and the beginning of the daughter’s, and one of them, in the Michigan collection, has now been added to by the identification of a little strip, 240 millimetres long and at most 35 wide, containing parts of 38 lines from these two speeches. The new papyrus was published a few months ago by Cornelia Römer in the journal Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, volume 182, pages 112-120 (the article is in English). Here is my translation of these 38 lines (plus a few more that follow them) as they can now be provisionally reconstructed.

SMIKRINES: … You’ll find her a good-for-nothing, slandering, schemer of a woman, and she’ll bad-mouth you. She won’t be asked to contribute anything to the family’s livelihood, but she’ll have an equal share in it, and she can expect to have a fine, trouble-free life! And your behaviour will only encourage her in this: you’ll always be looking cross, always telling him off, acting like a wife who feels thoroughly cut up. And that’s what will be your undoing. It’s hard, Pamphile, for a free woman to compete with a whore. She has more dirty tricks, she knows more, she’ll stop at nothing, she’s a better flatterer, she’ll stoop to anything without shame. You can safely take it that the Delphic Oracle has told you this is exactly what’s going to happen. And so you can set this firmly in your mind: you’ll never be able to do anything unless he’s willing!

PAMPHILE: Father, you’ve brought me up to speak my mind about everything, no matter what you may think is in my interest. Don’t take that away from me. I’m not a fool, and our kinship and your protective good will should induce you rather to take notice of what I say. First of all, then, daddy, do you think it’s possible that I should have managed never to do my husband any wrong? All right, let’s not talk about women who have erred. In the second place: you put on him the responsibility for what he’s done to me. But it’s nothing shameful. Not many people know the exact whole truth; most of them only know the bare facts, and say that he’s getting his own back on me for his misfortune, in face of the truth. And I, you say, must shun him as if he were a slave like Onesimos! What you said just now was a shameful thing to utter. “He’ll be ruined.” And because of that I’m to leave him? Did I come to this rich man’s home only to share his good fortune, and to betray him if he fell into poverty? No, so may Zeus be kind to me! I came to be the partner of his fortune and his life. Has he stumbled? Then I’ll bear it for the future – him keeping up two homes, having that woman lead him by the nose, always paying attention to her … . If you’re going to give me to a new husband on the terms that nothing bad or painful will ever happen to me, then I’m fine with that … . But if that’s unpredictable …

… which of course it is. It is notable how in the early part of that speech Pamphile hints at the truth of which her father knows nothing: she did (or so she believes) do her husband wrong by marrying him when she was pregnant with another man’s child, and never telling him.

The rediscovery of an ancient text can be a positive feedback process: the more of the text we have, the likelier it becomes that further portions of it can be readily identified. It is quite likely that our knowledge of Epitrepontes will advance at least as much in the next four decades as it has in the last four. In the meantime, it is already one of the gems of ancient light drama.

(Concluded)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply