November 29, 2012, by Alan Sommerstein

From Mount Sinai to Michigan: the discovery of Menander’s Epitrepontes (part 3)

From Mount Sinai to Michigan: the recovery of Menander’s Epitrepontes (part 3)

The fifth-century manuscript from Aphroditopolis in Upper Egypt, which came to light in the first decade of the twentieth century, proved to have had a chequered history. Some hundred years after it had been written, its then owner, a man named Flavius Dioscorus, had taken its leaves apart and used them as covers for his business documents. When those that could be found were put together again, they turned out to contain parts of six ancient comedies (it is all but certain that the manuscript once contained others too, which have been lost completely). One of these was a play called The Demes by Eupolis, who lived a century before Menander (but curiously, like him, died a premature and watery death, in his case as a casualty of a naval battle); this text must have been quite a rarity at the time when it was copied. The other five were all by Menander. Four were soon identified as Heros (The Hero), Epitrepontes, Perikeiromene (Shorn), and Samia (The Woman from Samos); the fifth has never been identified at all and is still known only as “the unidentified play” (Fabula Incerta).

The identification of Epitrepontes was easy: the manuscript contained a number of passages which were quoted by various later ancient authors as coming from Epitrepontes. What was more, the very first preserved scene featured two men “taking a dispute to arbitration”, which is what Epitrepontes means: they are quarrelling over the issue of who owns the trinkets that were found with the baby discovered in the woods, and one of them says “We’ve got to submit this to some arbitrator” (epitrepteon tini). And they do, asking the first man they meet to adjudicate their dispute – not knowing, any more than he himself does, that he is in fact the baby’s grandfather (but the theatre audience probably do know it; Menander usually has a god appear to tell them key facts like this in advance, though no text of such a speech in Epitrepontes has yet appeared).

It was now possible to read what looked like almost the whole of the play’s second act (out of five) and most of the third; the fourth and fifth were scrappier, but they included some crucial scenes, like the one in which the young husband, Charisios, is told who is the real mother of his supposedly bastard child – and can’t take it in because it’s too good to be true:

HABROTONON: Calm down, sweetie! The baby’s mother is no one but your own wedded wife.

CHARISIOS: If only she was!

HABROTONON: She is, I swear it!

CHARISIOS: What’s this yarn you’re spinning?

HABROTONON: What is it? The truth!

CHARISIOS [puzzled]: The baby Pamphile’s? But it was mine!

HABROTONON: Yes, it’s yours too!

CHARISIOS: Pamphile’s? Habrotonon, I beg you, don’t raise my hopes for nothing …

at which point, alas, the manuscript gives up on us for several lines.

Before long it was perceived that one of the two leaves in St Petersburg also belonged to the same play. The name Charisios was a link, and the situation fitted (a father-in-law complaining about the squandering of his daughter’s dowry, exactly as Charisios’ father-in-law does later in the play). The fragment included a break between two acts, and as the ends of acts two, three and four were already identifiable, this had to be the end of act one.

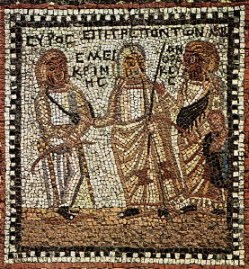

And for something like two-thirds of a century that was about all – except for one discovery made in the early 1960s. In a house excavated at Mytilene, on the island of Lesbos, were found a set of mosaics, probably of the fourth century AD. One depicted Menander himself, and the others showed iconic scenes from various plays of his, including Epitrepontes. This mosaic (the featured image for this series of posts) is labelled “Epitrepontes Act Two” and shows the arbitration scene. In the centre is the white-haired Smikrines, who is judging the dispute. He is flanked by the two disputants. On the viewer’s right is a man labelled Anthrakeus (the charcoal-burner), who is accompanied by a woman with a baby (she is only about half his size, partly in order not to unbalance the composition, partly because she is not really a character in the play – she never speaks). The man on the other side has slung over his shoulder a little black satchel; this presumably contains the trinkets found with the baby, which he has refused to hand over. It is unlikely that either the maker of the mosaic, or the man who commissioned it, had ever seen a performance of the play; they got some pretty elementary things wrong. The two disputants are almost as well dressed as Smikrines; in the play they are slaves, and Smikrines comments disparagingly on their rough clothing. And their names have got confused. The man with the satchel is named as Syros; in the play his name is Daos, and Syros (or Syriskos) is the other man, the charcoal-burner whose wife has the baby. It’s just as well that we have the Cairo manuscript.

All of a sudden, in 1983, other papyri began to come to light with text that clearly came from Epitrepontes and partly (never completely!) filled up many of the remaining gaps; by now, no less than ten of them. More on these, and what they have to tell us, in next week’s final instalment.

(To be continued)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply