August 14, 2013, by Warren Pearce

More heat than light? Climate catastrophe and the Hiroshima bomb

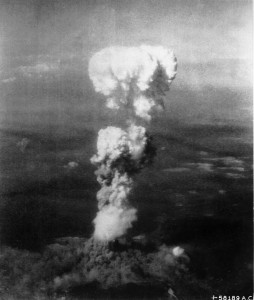

There has been some discussion on Twitter today (14 August) about the wisdom or otherwise of measuring the heat being retained by the Earth in terms of Hiroshima bombs. The analogy is presented by John Cook and Dana Nuccitelli on their Skeptical Science blog, drawing on an academic paper by Church et al to describe the heat retained as equivalent to four Hiroshima bombs per second.

I have no reason to doubt this. However, choosing the most effective metaphor involves more than simply finding an analogy that accurately conveys a specific energy equivalence. The very purpose of a metaphor is to help make the incomprehensible familiar in order to make a point. Asking whether it is accurate or not is not enough.

A problematic problem

The persistent problem with attempting to communicate climate change is that it represents an un-situated risk. As Mike Hulme describes it in Why We Disagree About Climate Change (p.196):

The source of the risk is distant and intangible – no-one can see climate changing or feel it happening – and the causes of the risk are diffuse and hard to situate.

Of course this is not to say that climate change is not a problem. However, the very nature of the problem is itself problematic. It is difficult to motivate political action around a problem which is so intangible, particularly when compared to classic environmental problems such as smog, floods, acid rain etc. which are localised and material. (As an aside, perhaps this means climate change is not an environmental problem at all?)

In this context, one can see the constant problem facing the ‘climate change communicator’:

Q: “How can we make this un-situated, incrementally increasing risk ‘real’ to the general public?”

A: “How about atomic bombs? Situated risks don’t come much bigger than that…”

So the Hiroshima meme was born.

To reiterate I am not casting aspersions on the accuracy of the data comparing the heat released by Hiroshima bombs to that being retained in the atmosphere. Rather, it is worth looking briefly at what lies behind the Hiroshima analogy.

Framing is political

In their classic paper Framing Theory, Chong and Druckman explain that the way an issue is presented, or ‘framed’, can work by “making certain available beliefs applicable or ‘strong’ in people’s evaluations” (p.110). So atomic bombs are a well-known concept, and provide a shortcut to ‘lay’ publics’ understanding the heat retention issue without any knowledge of the science: it invokes the notion of imminent catastrophe (what could be more catastrophic than an atomic bomb?!).

As such, it *is* scary – although Nuccitelli and Cook claim “it isn’t used because it’s scary, it’s simply about communicating the sheer amount of heat our planet is accumulating”. Even if the effect was unintentional, linking climate change to Hiroshima fits with a pattern of actors in the political debate using what Glynos and Howarth call “horrific logics” (see pp.11-12 for an introduction) in an attempt to make a particular policy idea “grip” the public. Imminent catastrophes have been used by both advocates and sceptics: for example, the notion that we have only “100 months to save our climate” or that a pro-renewables policy will lead to the countryside being ‘carpeted’ in wind turbines.

In addition, Hiroshima emphasises the man-made nature of climate change, a constant theme of climate change communicators keen to debunk the idea that natural variability in climate is more significant than the contribution from increases in carbon emissions. So even though the Tōhoku earthquake/tsunami of 2011 is a far more recent catastrophe than Hiroshima, using it to communicate energy flows would risk implying that climate change is a natural, rather than a man-made, phenomenon. In addition, Tōhoku released around 580 million times more energy than one Hiroshima bomb. So one could choose to say that the heat being retained is equivalent to a Tōhoku every four and a half years. It’s no less accurate in communicating units of energy, but maybe that doesn’t sound quite as scary as four Hiroshimas per second…

The window test

So without disputing the science behind the Hiroshima meme, one can see that the choice of *that particular* unit of comparison to communicate energy retention is a political one, framing the climate change problem as both man-made and catastrophic. However, the ever-present challenge in communicating climate change remains what one might call ‘the window test’. That is, there is a gargantuan gap between the rhetoric of four Hiroshima bombs per second and what I can perceive looking out of my window. Looking out of my window for evidence may be highly unscientific, but it is a response one might expect when talking about a risk which is un-situated in time and space in catastrophic terms.

So rather than being an effective communications strategy, framing climate change in catastrophic terms may generate more heat than light, and has the potential to reduce public support for policy in the absence of material evidence of catastrophes. If four Hiroshimas per second result only in an intangible, incremental risk, rather than an *actual* catastrophe equivalent to Hiroshima, one might reach the opposite conclusion from that intended: that the earth is actually quite resilient to such energy retention, and that four Hiroshimas per second isn’t anything to worry about. This would not be a good outcome for advocates of climate change mitigation policies.

So perhaps a less sensational means of communication might be more effective. One candidate is the idea of the atmosphere as a bathtub, that is gradually being filled up by carbon emissions. One can argue about how big the bathtub is, the rate at which it is filling, and what happens when it overflows. However it does more effectively communicate the nuances of the potential effects of climate change, and the incrementally increasing risk, rather than the context-free, catastrophic climate porn of the Hiroshima meme.

Nice to see one that we sort-of agree on Warren. I was only musing today that it’s difficult even for me, who fully supports the objectives of John Cook et al, to envisage on an emotional level (as opposed to an intellectual one) ‘four Hiroshimas’ of heat meaningfully. The default for me is visions of mushroom clouds marching across the landscape at the rate of 4 per second, which isn’t very helpful.

On the other hand the bathtub analogy is very apt when, for example, explaining that, yes, heat IS still escaping into space, but it’s the faster filling up of the bathtub that’s the problem. Although in other circumstances, such as when trying to communicate the urgency of the need for mitigation, it can (IMO) produce a deceptively calm and unhurried image.

The Hiroshimas analogy is useful in one respect: for anyone who’s able to grasp sheer numbers, and putting aside any objections of sensationalist / catastrophist imagery, it’s easily quantifiable as an amount of heat that is, plainly, A Lot.

There’s a place for both the atomic bomb and the bathtub, IMO.

Hi Jeremy. Yes I also thought of marching mushrooms but didn’t put it as snappily as you just have.

Yes it does communicate the amount of energy involved as *large*, but I’m not sure it’s possible to bracket that off from the catastrophic nature of Hiroshima.

What I didn’t say in the post is that although four Hiroshimas p/sec sounds a lot, I don’t have anything to compare it to. What would be an acceptable amount of Hiroshimas for us to be retaining. I know that heat retention via the greenhouse effect enables Earth to support life, so presumably a certain number of Hiroshimas is actually a good thing…

The bathtub analogy misses the point. We’re trying to communicate the immense amount of global heat accumulation in terms that people can understand. Tell them it’s 2.5 x 10^14 Joules per second and you’ll get a blank stare. 4 Hiroshima atomic bomb detonations per second are easy to visualize. Everybody has a pretty good idea how large the Hiroshima atomic bomb detonation was, and 4 per second is an easy frequency to visualize.

If you have a better analogy, we’re open to suggestions. We tried a lot of different units of energy, and none were even close to being as easy to visualize as 4 Hiros per second. But just calling it “climate porn” isn’t constructive.

Thanks for your comment Dana. With the greatest respect, I am not ‘just calling it climate porn’. From pp.13-14 of the Warm Words report I link to at the end of my piece (published by IPPR, hardly a bastion of climate sceptics):

*Whether or not* it is accurate, focusing on the “immense” nature of the heat accumulation is actually likely to turn people off acting on the problem, rather than focusing minds (I assume the latter is your preferred aim). And I simply do not accept that one can bracket off the catastrophic and horrific nature of Hiroshima and use it simply as an alternative unit of energy comparison.

Even if one continued to think that communicating a problem as immense and catastrophic was a good engagement tool, I would bet that all possible alternative units of measurement (such as Tōhoku) are naturally occurring, rather than man-made. For reasons of framing which I outline in the post, this is also probably not a good comms strategy.

Finally, you say that telling people global heat is accumulating at a rate 2.5 x 10^14 Joules per second brings a blank stare. I find this unsurprising, as it seems unlikely that the people you are telling actually asked you how much heat is accumulating in the first place. Some people are interested in the science, and that is great. But most people, if they are interested in climate change at all, are concerned only with the material consequences for them. Describing scientific findings in terms of Hiroshima is a political move which invokes particular material (catastrophic) consequences. However, it does so in a manner which may make arguments for climate actions to be taken less seriously in the future. My advice, FWIW, is to focus on how a changing climate may affect society in the future (I’m sure you do this already btw). This will hopefully lead to more serious discussions about policy, rather than attempting to justify particular courses of action through self-defeating catastrophic imagery.

Warren, I think you’re overstating your case against the energy-released-by-atomic-bombs analogy.

So long as the sums add up (that being the crux of the matter) there is space for it.

As I mentioned above, I had to think about the analogy when I first came across it, to separate out the mushroom clouds picture from the ‘heat’, and can see that it could be a counter-productive analogy if used in an alarmist fashion (running around waving ones arms and yelling “Arrrghhhh! Four atomic bombs per second! We’re all going to die! We’re all going to DIE, I tell you!” for example). But when thought about – and presented – in a less heated (ha ha ha ‘scuse the pun) fashion it can, IMO, be useful. At least until an equally arresting but less fraught analogy comes along, that makes the point as forcefully.

We use the 4 Hiros analogy specifically to debunk the ‘global warming pause’ myth. During the time contrarians claim global warming has ‘paused’ (the past 15 years), the global climate has accumulated heat at a rate of 4 Hiros per second. It’s a very effective message for debunking that particular myth, as you can see from the media coverage it received.

http://www.skepticalscience.com/republishers.php?a=hiromedia

I simply don’t buy the argument that the 4 Hiros message will make people curl up into a fetal position and wet their pants. It’s not like we’re saying climate change will drop an atomic bomb on your house.

The Hiroshima bomb analogy also misses the point, because it’s a childish way of describing the issue.

A much better way, would have been to make it personal, as catastrophists love to do, such as how long one lays naked in direct sunlight on a hot summer day.

So, it was basically a missed opportunity.

NB: I was around when the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Isn’t 4 hiroshimas per second + or – 117 hiroshimas per second error in the messurement?

Plus the Sun does about 4000 hiroshimas per second? I remember another blog doing similar calculations. As Warren has been doing the maths, I imagine he can do the calculations.

Either way I think the public are immune now to this sort of framing, that’s if thry are listening at all.

Maybe Dana can explain why they would listen to Skepticsl Science, wherefor fun they photo shop esch other as Nazi’s or is there a completely rational sensible reason for that?

Its scare-mongering, Dana. No amount of bluff and bluster can get past that. Pretty much everyone knows the challenges to be met in the face of climate change, but this is an example of the type of communication of science that just drives people to tune out. You risk being labelled in the same category as Al Gore. Started off well, but now more ridiculed than admired.

Isn’t watt per square meter a fine unit? Relatively intuitive, neutral and scientific. If that is still too complex, you can compute it as a percentage and divide it by the energy flux that comes from the sun.

Both Hiroshima bomb and Tōhoku are inappropriate. Not only that they clearly elicit an emotional response, and are also abstract as energy unit (you think of the outcome not of the energy contained), but also because these are energy pulses highly located in space and time and as such produce a completely different outcome. Tōhoku is even more inappropriate as it suggests that climate change in natural. Which is an untenable position in 2013.

Yes, looking out of my window for evidence is very unscientific and very un-allmost everything. It would lead to saying there is no evidence for crime, terror, accidents, unemployment, economic growth, biodiversity loss, corruption, etc.

Point about thinking about outcomes is good. Didn’t state that directly in the piece.

Take your point about the window test, (although it doesn’t stop people doing it!) However, a lot of your examples would have anecdotal evidence available eg crime, unemployment, which people may base their beliefs on. There is evidence that people do this with climate change as well, but in terms of recent experience of unusual weather. See this paper by Hamilton & Stampone on temperature change and fluctuating belief in AGW http://pubpages.unh.edu/~lch/Hamilton_Stampone_2013.pdf

John Cook’s experience in using the 4 Hiros analogy in talks and the audience reaction contradicts your speculation.

@Dana

That is (1) casual empiricism and (2) an appeal to authority.

… but why is that a problem, if there’s no hard evidence out there one way or the other? To my mind it should only be seen as a dubious approach if it’s used to try to contradict or undermine more concrete evidence, or in some other fashion that’s clearly unreasonable.

Even Warren’s post is largely based upon opinion and – e.g. the IPPR quote – writing that doesn’t cite empirical evidence. As such even the IPPR quote could be described as an appeal to authority.

Doesn’t cite empirical evidence? Warm Words is primary research.

From the report preface (p.6):

“The research was carried out in late 2005 and early 2006. It involved reviewing some 600 articles from the UK daily and weekly press and magazines, about 40 television and radio advertisements and news clips, and 30 press advertisements. It also analysed around 20 websites”

I might add, not only is ‘Warm Words’ primary research, but it covers an impressive breadth of material – sadly uncommon in many research papers.

Point taken Warren: it was perhaps careless wording on my part. I was specifically referring to the paragraph you quoted in your response rather than the entire report. I stand corrected!

Why?

How many people actually know the amount of heat an atom bomb created?

My guess is, Cook thinks his audience was impressed, and they probably were, because an atom bomb “sounds” BIG.

And 4 per second?

Not something anyone can work out on the back of an envelope, is it, Dana?

Can I ask; how does someones experience get put on an equation line against someones speculation?

What do you think you are you communicating when you do this, and to whom do you think you are communicating?

Does that target audience have opposable thumbs?

Warren, I think you misconstrue both *what* we’re trying to achieve with the Hiroshima A-bomb metaphor and *why* we use the metaphor.

What we’re trying to achieve is very specific – communicate the simple fact that our planet continues to build up heat. We’re not looking to solve every climate communication problem with a single metaphor but address a very specific misconception. A persistent question brought up by many online commentators is whether global warming is still happening. The answer is that the laws of physics continue to operate since 1998 and the greenhouse effect is still blazing away. The planet is still building up heat.

A lot of people would like to ignore the planetary energy imbalance and focus instead on short periods of the surface temperature record where the warming trend has slowed somewhat. But genuine scientific sceptics consider the full body of evidence – the surface temperature trend *and* the total heat content of our planet. It’s only by considering both that one can come to a proper understanding of what’s happening with global warming. The purpose of the metaphor is to raise awareness of the planetary energy imbalance.

I fully agree with you that talking about climate impacts on society are an important message. In fact, one of the most important climate messages. But that doesn’t change the fact that there are specific misconceptions out there that require specific responses.

As for *why* I use this metaphor, the reason is not political. It’s cognitive. There are several decades of psychological research into misinformation and how to reduce its influence. I could cite lots of papers and explain all the cognitive processes involved but for brevity’s sake, let me sum up the research with 6 words: “fight sticky ideas with stickier ideas”. To debunk a myth, you not only need to show the myth is false, you also need to replace it with a more compelling, alternative narrative. A “sticky” message needs to share some of the following traits: simple, unexpected, concrete, credible, emotional and tell a story. Of all the metaphors explaining the planetary energy imbalance, the Hiroshima metaphor ticks more “sticky” boxes than any other metaphor I’ve encountered.

That’s not to say it’s perfect. Like all metaphors that use simple examples to explain complex phenomena, the metaphor breaks down at some point. An A-bomb is localised while global warming is, well, global. Also, I can see how it could be perceived as being used for political reasons. But that doesn’t change the fact that on a purely cognitive level, it’s a powerful and effective metaphor. However, if you can come up with a better metaphor to explain the planetary energy imbalance in a compelling, “sticky” fashion, I’d happily adopt it and give you all the credit 🙂

WRT to comments regarding “imbalance”.

I presume you mean “balance”. It is always in balance, as a basic law of physics.

Perhaps you mean to say something like “dynamic state” etc.

Hello John – thanks for commenting. I should say I am also a devotee of the Heath Brothers, and use that book to try and explain to students why they should avoid Death by Powerpoint.

What you say makes sense. I guess where we might part company is over the importance of correcting scientific misunderstandings/errors/misinformation/whatever one calls it. I *don’t* think it’s unimportant, but neither do I happen to think it’s very important in terms of driving policy (which I am assuming is an ultimate aim of yours – if not, then apologies). I speak from the UK, where there is pretty much a cross-party consensus on climate policy. I know in the US, and to some extent Australia, the science and motives of scientists have been questioned more openly by politicians. I can’t really imagine mainstream pol’s doing that in the UK. Even so, I’m very uncertain regarding the extent to which science drives policy.

Re the metaphor, I don’t disagree that it’s sticky. It’s very sticky. However, I really don’t think it can be bracketed off from it’s catastrophic overtones, particularly in the historic context of such imagery being used to communicate climate change.

Finally, you ask if I can provide a less catastrophic metaphor which is as sticky as Hiroshima. As I say above, other candidates would probably be ruled out as they are naturally occurring so would not be useful framing devices for talking about man-made climate change. So I’m not sure if there is one available or not. Personally, I wouldn’t be too bothered as I’m not sure how important the fact is in the first place. But again, I fear we may have to agree to disagree on that one…

Warren, the only cross-party consensus on climate policy in the UK is the consensus not to take climate change seriously… As was evidenced by the failure of the Energy Bill to be amended to commit the UK to setting carbon reduction targets.

[…] Full story […]

The Hiroshima analogy seems a case of excessive computing power in the hands of the numerical illiterate. Is 4 nukes a second an “immense” amount of energy? Yes on a human scale, no at planetary level.

The US national debt, for example, grows at one Freedom Tower per day ($3.8 billion). Is that an “immense” amount of money? It will take Berlusconi 100 years to give that amount to his former wife, 100,000 bucks every single day. But for the USA as a whole is less than peanuts. Won’t even try to describe how insignificant it is at a global level.

So the analogy is only meaningful as long as the audience is left in its maths ignorance. That’s unsurprising, coming from SkS.

As device to explain a complex phenomenon ni an objective manner, the Hiroshima analogy is fatally flawed. The reason is because it excludes, or possibly is an attempt to divert attention from, an important piece of information – scale.

“Hiroshimas” elicit a strong emotional response to absolute size. But the energy balance question is one of scale. Someone being told that the energy in the system is increasing at “4 Hiroshimas per second” will not get any proper insight into whether this is significant or even material.

Hi Warren, an interesting post, you always make pertinent points. I have a question that is always at the back of my mind when I read your posts on matters of climate change scepticism though, and in particular when you are critical of communications approaches such as these: what are you hoping to achieve?

I only ask because in some ways I think it cuts to the heart of the subject matter you study. For example here you suggest that ‘presumably’ Dana and John want to communicate climate change more effectively. But do you? I can certainly say for myself that I do, and to the extent that I criticise others’ approaches, it is only ever with a view to doing better at engaging people in the challenge of confronting climate change. But I think perhaps you don’t share this goal, or see it as inappropriate. Are you of the same view as Tamsin, that climate scientists should be seen but not heard (to misuse a phrase)?!

Could you clarify your position perhaps? When you defend scepticism, and criticise Dana & John, what is it that you see as your main motivation for that?

thanks,

Adam

Hi Adam,

I’m not sure that I have ever defended sceptics, unless that’s a synonym for ‘not attacking sceptics’ (I didn’t think I was particularly kind about sceptics in my Guardian piece, but others obviously disagreed). As I commented under your post here http://talkingclimate.org/scientists-sceptics-and-advocates/ I did not argue that sceptics are the true defenders of scientific method – only that that story is an important part of their arguments (talking extremely broad brush here, lots of nuances between bloggers etc).

You ask me about my motives. My motive for writing this post was to explore the use of a very striking metaphor being used in climate communication, what might lie behind that, and offer an argument on why it might not be helpful despite being accurate. I proposed an alternative (the bathtub) which is used by Tyndall Centre scientists – not regarded as a sceptic-friendly bunch. John and Dana don’t seem particularly keen on it. That’s fine. I’m not sure the Tamsin question really applies, as she is talking about climate scientists, while I would think of John and Dana as specialist science communicators rather than climate scientists.

Am I interested in communicating climate change more effectively? This is an interesting question, as I have come across a few people who seem to assume that my research is about science communication. I accept that our ‘Making Science Public’ can be interpreted in multiple ways – that’s part of its strength. But *nowhere* in the research aims of the programme or in the detail of the research projects is science communication mentioned at all. (Not that I assume people will spend their time poring over such pages, but want to be clear now). My scepticism project is 2.3 on the second of these links – it doesn’t say anything about scientific communication. It talks about shifts in scepticism, knowledge production and the interpretive space between rational-scientific knowledge and the social-political world. Following Wittgenstein, I have an interest in language, and metaphors were part of my doctoral work, hence my writing this post. Being any kind of scientist involves communication of some sort, but ‘science communication’ as it is typically framed is not a current research interest.

Hopefully this post won’t be seen as being too off-topic!

I’ve just read through the various programme / project description pages you provided links to Warren. A very interesting project overall, and your ‘2.3.’ section specifically.

Reading those pages has brought into focus one or two thoughts I’ve had over the past couple of days about ‘climate scepticism’ and the Making Science Public programme. Putting aside for the time being any considerations of the appropriateness or otherwise of some specific labels, I’d be grateful if you could clarify a couple of things.

Firstly, do you believe that there is widespread misinformation and misrepresentation of climate science and the motivations and honesty of climate scientists, the primary purpose of that misrepresentation apparently being to discredit those findings of climate science that point to potentially dangerous anthropogenic climate change, and so to steer public and policy responses away from taking mitigatory action?

Secondly, if you do accept that, how will you and your co-workers in Making Science Public distinguish misinformation, whether one-off comments of the simply misinformed, or concerted and sustained campaigns or programmes masquerading as scepticism, from genuine scepticism and good science?

I’m not trying to make things difficult here: these seem to be crucial considerations for any study that considers climate scepticism, but I haven’t yet seen a clear explanation of how, or even whether, they will be tackled by the programme.

When Adam “criticise others’ approaches, it is only ever with a view to doing better at engaging people in the challenge of confronting climate change”.

Isn’t this a somewhat frank, albeit unwitting reflection on Adam Corner’s own motivations?

What if, for example, the rights and wrongs of ‘engaging people in the challenge of confronting climate change’ were to be explored, and found wanting? And what if it was discovered that some academics had eschewed the idea that they should try to form an objective understanding of what was happening in society, to use their campuses as campaigning platforms instead… And what if some social scientists wanted to comment on that, fairly significant transformation of the role between the academy, the public, and politics?

To what extent is is the researcher’s role and responsibility to ‘engage’ the public in a political project? And how can such a researcher demand that others give a full account of their motivations — seemingly to make sure that they are sufficiently pure?

What is particularly striking about Adam’s question is that it seems to imply that Warren’s criticism of the Hiroshima analogy isn’t aiming towards progress in the debate. Indeed, criticising the absurd hyperbole that emerges from the SkS project might give the wrong people an edge in a political debate. But that surely would be progress, if it had led to a better argument emerging, even if it wasn’t the Cook tribe who benefited from it.

Is the Hiroshima analogy wrong simply because it’s the wrong strategy? Doesn’t its wrongness, consistent with the wrongness of other pseudo-academic studies to come out of the SkS project recently, reflect a deeper problem with the thinking going on in its author’s heads?

As far as I can see, it started with an article in the Sydney Morning Herald, which incorrectly attributed it to ‘climate scientists’, when in fact it came from Mr Cook.

Here’s a selection of tweets about it from climate scientists, that can be added to the opinion of Victor above.

Andreas Schmittner @ASchmittner These are the sort of catastrophic messages I don’t

like. Just don’t compare climate change to A-bombs, will you? Its not!

Doug McNeall @dougmcneall Comparing climate change to A-bombs like this is utterly

meaningless.

O. Bothe @geschichtenpost Dear scientists, we don’t have to use big scary metaphors “to market”

research, really, that’s not necessary (and reduces trust? oops.)

O. Bothe @geschichtenpost framing as A-bombs is much too emotionally loaded

As I think I have said before, cheerleaders like Dana and John damage the credibility of climate science and give fuel to the sceptics.

I find the stated purpose of this metaphor baffling. John Cook says:

The metaphor doesn’t do this, at all. It does nothing to tell people why, even though “our planet continues to build up heat,” they don’t see anything that suggests it is true. It does no more to address that issue than simply saying, “The planet is continuing to warm.” There is no connection between the metaphor and the stated purpose!

According to John Cook, he’s using a scary metaphor that has no connection to the issue he wants to address. That’s about the worst condemnation of the metaphor one could offer.

The ideas expressed by Cook and his associate express considerable naivete, even allowing they only seek to communicate magnitude of a heat quantity by this Hiroshima exercise. It has been widely argued in the climate social sciences literature that employing catastrophe to produce intended effect, though may appeal to the communicator by appearing “sticky” (call it what you will), has a host of effects that eventually negate the approach. This, when referring to the use of weather-related imagery and actual weather disasters, which though may have severe problems with attribution, are at least superficially plausibly related to the phenomenon of climate change.

The Hiroshima bomb, in turn, has nothing to do with climate, and the only reason for it to ‘stick’ in anyone’s mind is the devastation it wrought on the city. In other words, the power of the bomb, that correlates with the heat quantity, is “sticky” only by virtue of its mass murder. This simple fact could not have missed Cook.

Cognitive research is not carried out in a vacuum, leave alone a moral vacuum. Several times, it functions in a retrospective way, identifying what factors might have lead to easy acceptance of a given fact. To abstract such points and use them prospectively to justify gratuitous and violent imagery, as Cook as done here, constitutes malpractice.

Consider Heartland’s billboard exercise with the Ted Kaczynski image. The connection they wanted to make was how extremists like Kaczynski easily accepted the concept of anthropogenic global warming. The anti-Heartland activists went on a rampage highlighting the polarizing comparison of climate believers to mass murderers. These included Skepticalscience! At the time Heartland stated:

To which Rob Honeycutt, one of Cook’s devout supporters replied:

***please ensure all comments remain ON TOPIC***

Future references to matters unrelated to this post will be deleted without warning 🙂

As humans emit from breathing around 8% of what they release from fossil fuels etc, is John Cook claiming that by the mere act of living, humans are exploding one Hiroshima bomb every 3 seconds?

The answer to that question is no. The question itself reveals a lack of insight into the nature of the climate change problem.

The CO2 humans (and any other respiring organism) breathe out has only recently – generally within the past year or two – been removed from the atmosphere, via photosynthesis and thence into the food chain. It is entirely different, in terms of impact on carbon concentrations in the atmosphere, from ‘fossil’ carbon.

That’s very interesting Jeremy. Is CO2 produced from human breathing of a fundamentally different nature than “fossil” CO2? Does it not behave like a GHG, perhaps?

I don’t think even John Cook goes as far as claiming that. But there is alway time to learn something new.

Maurizio, there’s a fundamental difference between short-term cycling of carbon from and back to the atmosphere via, for example, photosynthesis -> food chain -> respiration by humans, and the release of carbon that was last in the atmosphere millions of years ago.

It’s difficult to express just how basic a concept that is.

Nice interesting article, thank you. Since I’m tired of converting between toes, twhys, boes, btus, mcfs and all the rest of them, let alone hiroshimas, I’d agree with commenters suggesting watts, joules and meters as the units of choice.

What might make more sense and has something tangible to it, is how this energy would affect the OCEANS, since they oceans have such a great ‘buffer’ capacity from a heat standpoint.

So, over 1 year, how much would this ‘hiroshima bomb’ energy warm the oceans? I haven’t done the math, but I might suspect that it is a small fraction of a degree . . .

. . which that then wouldn’t be ‘scary’ enough; thus they way it is presented in ‘hiroshima bomb’ equivalents . . .

The Met Office just released a report saying that the iceans warmed by 0.09C over 55 years! (Not an error bar in sight)

I think we the oceans and the planet are going to be ok

How many thousandths of a degree C (unmeasureable) in ocean warming, does this decade’s missing 0.2 degree C of global air surface temperature represent?

Let alone that 0.9C in 55 yrs number is just guess work built on assumptions, with very sketchty data. And it mentioned those issues in the report!

The measure of global waming, politicaly, scuentifically and otherwise for 30 yrs has been global AIR surface temperature. So good luck with the goalpost shift. Additionally when Skeptical Science show an ocean global warming graph, they show a more conventional joules graph label. If it of course was represented by tenths and hundredths of degrees C, any casual observer will see the nonsense of that graph

That is to be clear 0.09C ‘rise’ in ocean temperature over 55 years, according to Met Office, via Doug Mcneall of the Met Office

https://twitter.com/dougmcneall/status/360347024891183104

SkS’ only link to fame is their ability to dress up irrelevant half-truths as scientific-looking blathering, thereby fooling the unsuspecting readers just as they fool their “4 Hiroshimas” audiences. It’s all true but there is no discernible reason to care about it.

It will be interesting to see how SkS will fare against AR5.

Barry, in a sense, you’re illustrating the issue and almost doing the same as SkS, but in reverse. You’ve quoted a small number. The oceans have only warmed by 0.09 degrees celsius in 55 years. Why do we care, is what you’re saying. However, this required something like 3 x 10^23 Joules of energy because the oceans are a massive heat sink. If the global energy imbalance remains at around 10^22 Joules per year and if 99% of this energy goes into the oceans the ocean temperature will indeed rise slowly (about 0.04 degrees per decade). If, however, only 1% of the energy imbalance heats the land and atmosphere, surface temperatures will rise by around 0.1 degrees per decade. If a bigger fraction heats the land and atmosphere, then temperatures will rise even faster. So, maybe you think that it is possible that all of the excess energy will go into the oceans and temperatures will continue to rise slowly. The laws of physics would tend to disagree.

Anyway, the point I’m making is that you seem to be criticising SkS for using a number that seem big and scary and then quote a number that seems small and insignificant. Do you not see the irony in this?

Lots of ifs

Including the if that the oceans have actually warmed by that much at all. All very sketchy, very poor historic data, etc

The theory is that ‘missing ‘ heat is going into the oceans, but of course depending on a number of factors, that it may not be missing at all.

The next several years of observed temps. Air and ocean will go a long way to resolving this

I use ifs partly to illustrate uncertainty. The ocean heat content data indicates that the ocean heat content has increased by 3 x 10^23 J since about 1970. There are errors associated with this data, but they don’t change this basic result by much. However, the real point of my comment was that you made what was, given the data, a reasonable statement (ocean temperatures have increased by 0.09 degrees C in 55 years), but because 0.09 is a small number you interpret this as insignificant or not important. However, the data you used is also consistent with the energy in the climate system (mainly the oceans) increasing by 4 atomic bombs per year, a somewhat more “scary” comparison. So, my point was simply that you appeared to want to use what appears to be a small number because that makes things seem insignificant while criticising those who make a comparison that makes it appear more “scary”. I find that a little ironic. Neither calculation is “wrong” but it’s clear that one can cast it as being insignificant or significant depending on the comparison that is being made.

Sorry, meant to say 4 atomic bombs per second, not per year.

Maurizio, there’s a fundamental difference between short-term cycling of carbon from and back to the atmosphere via, for example, photosynthesis -> food chain -> respiration by humans, and the release of carbon that was last in the atmosphere millions of years ago.

It’s difficult to express just how basic a concept that is.

First we are told by some people that we need to know 97% of scientists are safely consigned to some consensus and we should not think they have any interests outside that consensus.

Apparently it is important that the public know this is in order to move society to take action.

However that consensus is poorly defined.

Later we hear from the same people that 4 Hiroshima’s per second is the reality we live in.

Would it be too much of a surprise if the recipients of this series of informational nuggets then end up not really interested in what else this “97%” all agree on?

This isn’t really “communication” it is only escalating salesmanship. I think we’ve all seen it before and dealt with it.

Keep it up I say 😉

[…] Warren pointed out recently, science communication was not a topic mentioned in our original proposal, but has crept into the […]

[…] and creative satisfaction, but it can also lead to serious arguments (see for example Warren’s blog post about the Hiroshima bomb comparison in climate change communication). (There are, of course, […]

I think you’re being a little unfair on Cook and Nuccitelli and reading more into the analogy than warranted.

On the 6th of June, 2013, more than two months before your post and the Twitter discussion that triggered it, Australia’s ABC TV broadcast a story on fire tornadoes that you can watch here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqYEeivt8Eg

At the 9:50 mark, the host says:

Why did she say that? Was she trying to suggest that the fire was man-made and a “natural” example would have damaged that? No, the story clearly identified lightning as the culprit. Was she trying to scare people? No, the images of the fire itself already does that.

The reason is simple: people have an idea of what an atomic bomb looks like. We’ve all seen footage of them on TV, and pictures of the devastation they caused. (Remember that thankfully there are still only two examples you can point to of what they do to civilised areas, so that reduces the options somewhat.) We have some idea of the awesome amount of energy involved. And equating ten minutes of that fire to one Hiroshima atomic bomb emphasises just how big that fire was.

So Australia’s national broadcaster had already, without fuss, used the Hiroshima atomic bomb as a unit of energy to try to help people conceptualise something that is inherently hard to grasp. Cook and Nuccitelli did the same. Interestingly, it seems like they’re not the ones fussing over how this would be “received” or the impact this would have on attempts to get the “message” out or whether it’s “counterproductive”.

looks like Cook/Nuccitelli did not take on board the criticisms of the metaphor..

they have just launched a new App in the Guardian, with a mushroom cloud icon, for Hiroshima bombs per second

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2013/nov/25/global-warming-counter-widget

the website!

http://4hiroshimas.com/#About

(popcorn time?)

Climate scientist Scott Denning explained how much energy to John Cook, John was not impressed by Scott’s metaphor:

SkS forum:

“I asked various climate scientists for quotes on global warming and Scott Denning gave me this:

“Doubling CO2 in Earth’s atmosphere would add 4 watts to every square meter of the Earth’s surface. This is equivalent to running a child’s night light on every square meter permanently.”.

Somehow, 3 nuclear bombs per second sounds a lot more impressive than a child’s night light! “- J Cook