September 13, 2022, by UoN School of English

Exploring historical buildings and archaeological monuments in Bulgaria

At the end of August and beginning of September, I was asked to be part of a group funded by the European Union’s Erasmus + programme sent to Bulgaria to study Bulgarian heritage and culture; the particular focus of this placement was the conservation of historic buildings and archaeological monuments. The programme included first-hand experience and observation, reflecting on and discussing the particular challenges faced in sustaining heritage in Bulgaria over the 20th and 21st centuries, learning from various responses to those challenges, encompassing the successes and the downsides. The evidence of Bulgaria’s recent past abruptly juxtaposed to its deep past was a dominant impression.

1. 4th century Rotunda of Sveti Georgi within the Presidency and the Roman walls of Serdica underneath the former Bulgarian Communist Party House, Sofia.

Although much of the placement was conducted in English, I relished the chance to be immersed in Bulgarian language and Cyrillic script, armed with numerous dictionaries and language books, much to the amusement of the rest of my group. I had not visited Bulgaria before, although I have studied Ancient Near Eastern languages in the past – I found, then, a real fascination in places of language and cultural contact between east and west (Indo-European and Semitic families).

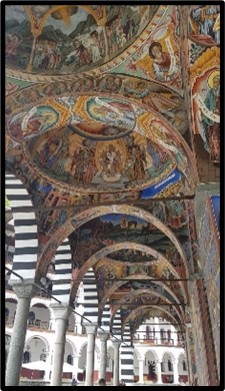

Bulgaria has a phenomenally long and varied past. (The number of UNESCO World Heritage sites we visited was notable.) Highlights include what is thought to be the world’s oldest worked gold from the Varna necropolis c.mid-5thmillennium BC, and the emergence of the Thracian civilization, who by the 1st millennium BC feature significantly in Homer, Herodotus and Roman commentators. The valley containing their monumental tombs is remarkable, both for the standing archaeology of the burial mounds and for the dramatic Balkans, mountain topography – something which is relevant to my own PhD research at Nottingham. Bulgaria was the focus of much activity in the history of early Christianity. Various people in the group, including myself, work closely with historic churches in Britain, so it was extremely helpful to see so many historic monasteries and churches within the Bulgarian Patriarchate, ranging from the site of the council of the early church fathers in Serdica (now underground in a shopping mall and metro station!), the frescoes in rock-cut caves high above the Rusenski Lom or the early church at Boyana, to the equally dramatic, but far more recently rebuilt monastery at Rila.

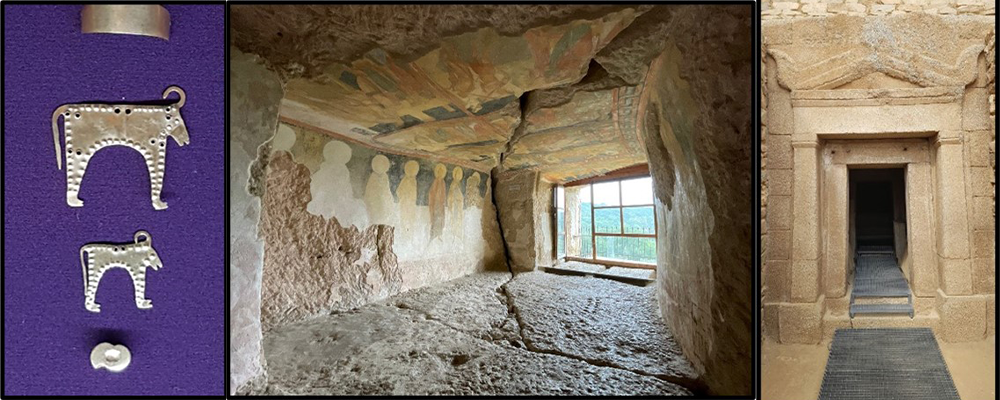

2. From L to R: Varna gold jewellery; the cave monastery of St Michael, Ivanovo; Thracian tomb

3. From L to R: Thracian helmet; gold mask (possibly Teres I?); Thracian burial mound and the Balkans

4. Rila monastery, frescoes

4. Rila monastery, mountainous settings

Topography, history and language stood out for me. Observing how settlements evolved identity relative to their geographical surroundings is part of my ongoing research and I love a topographically constrained site: Tsarevets, the 12th century capital of Bulgaria, surrounded by the looping gorges of the Yantra, was a particular favourite. Without doubt, I am incredibly grateful for the chance to see, think about and learn from such a range of topics and people in Bulgaria.

5. Tsarevets: Veliko Tarnovo

– Abigail Lloyd, Midlands4Cities-funded PhD student, working on hill place-names and settlement

(For more pictures see Twitter @Abi_on_a_hill)

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply