July 20, 2021, by eburke

Was There a Fourth Bomb?

A group of loyalist paramilitaries detonated three bombs on the night of 28 December 1972 – in the towns of Belturbet, Clones and near the village of Pettigo – which resulted in the murder of two children, Geraldine O’Reilly and Paddy Stanley, and the wounding of many others. But was there a fourth bomb?

The war diary and reports of the British Army’s 3 Brigade, in command of much of the border counties, gives an account of another bomb on the same night as the cross-border explosions. At 1940 a telephone operator received a call warning that there was a bomb in the Castle Vaults, a popular public house at the corner of Main Street and Manse Street in the County Down coastal village of Dundrum. The caller told the telephone operator that the bomb would detonate in ten minutes. A 2 ft by 2 ft cardboard box was found in a hallway in the pub with wires leading out of it. Soldiers from C Company, 9th/12th Lancers hurriedly cleared patrons and residents from the streets. Michael Cunningham, the catholic proprietor of the pub, carried his sick mother-in-law from her bed to safety.

Main Street Dundrum

The bomb did not initially detonate; a British Army ammunition technical officer (ATO) was requested to come to Dundrum. But this was a busy night. There were a number of bombs to deal with elsewhere, including in Lurgan and Crossmaglen. The bomb eventually exploded at 2235, five minutes before the ATO arrived. The Down Recorder described the damage:

The building was wrecked and windows in many nearby houses and shops were blown away. All householders had been warned, but such was the long delay that a few went back into their homes. In one case children were asleep in a bedroom which was showered by glass.

A witness claimed that two women had planted the bomb; another claimed that a man was present. In the hours after the bombing 3 Brigade reported that it was likely that local republicans had attacked the pub because its owner had served members of the security forces in the past and had been threatened if he did so again.

What makes this bomb stand out from the others in Northern Ireland that night and what potentially links it to the three bombs in the Republic of Ireland? The day after the explosion Captain Richard Wilkin, a 17th/21st Lancers officer serving in County Down, acted quickly to try to exploit a specific piece of intelligence he had received. Wilkin had a registration for a rental car – he suspected that the occupants had planted the bomb in Dundrum. The car had been rented from Hertz at Aldergrove international airport outside Belfast. It was due to be returned on 30 December, two days after the bombing.

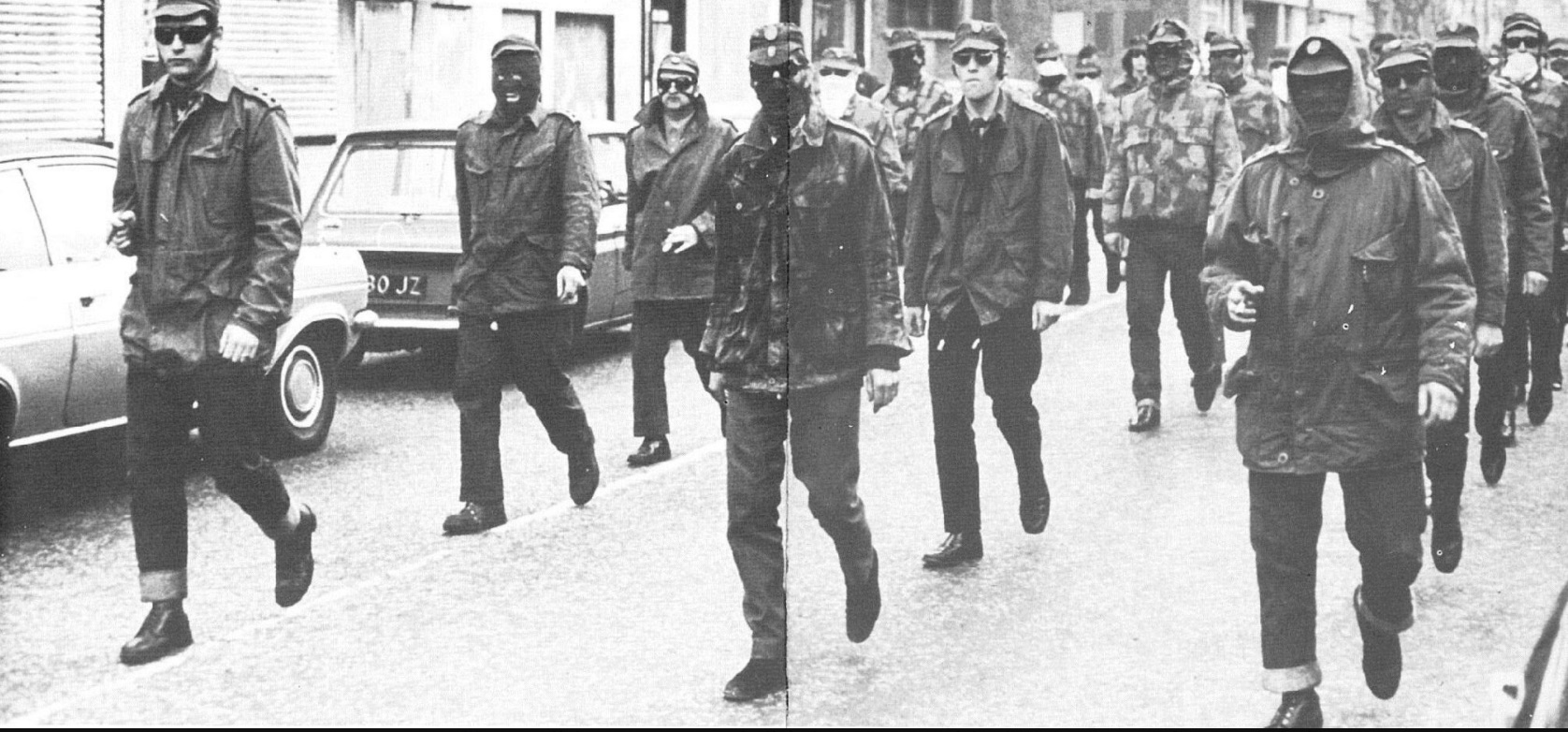

17th/21st Lancers

As I have written about previously, British Army intelligence officers believed that William McMurray was the commander of an Ulster Defence Association “commando” unit that was suspected of carrying out a series of bombings in the Republic of Ireland in late 1972 and early 1973. McMurray was a serial renter of cars from Aldergrove airport. The Barron Inquiry into loyalist bombings and campaigner and author Margaret Urwin have described in considerable detail loyalist paramilitaries’ use of rental cars from Aldergrove to carry out attacks during this period. A licence repeatedly used to rent these cars had been stolen in August 1972 from a man called Joseph Fleming who lived in Derby, England, but occasionally visited Northern Ireland. A car rented from Avis rentals (with Fleming’s licence) in Aldergrove later exploded in Dublin on the evening of 1 December 1972 – one of two bombs that detonated in Ireland’s capital that day that resulted in the deaths of two people (131 people were injured, some of them severely). A PSNI Historical Enquiries Team report into the murder of Louis Leonard, a Fermanagh butcher and republican, related how McMurray, a suspect in the Leonard case, hired a car from Avis in Aldergrove on 15 December. Leonard was shot dead that night in his shop in the village of Derrylin; when the car was returned on 18 December, Avis cleaners found four bullets in the ashtray. Aldergrove was heavily policed, not least since it was also an important British military base. The ease with which loyalists – men already well known to the police and military – repeatedly rented cars to carry out attacks, from the same companies and in the same location, has been a source of great resentment among the families of their victims.

Captain Wilkin and A Company, 17/21 Lancers asked the RUC for help to track down and intercept the renter of the Hertz vehicle suspected of involvement in the Dundrum bombing. The RUC, initially at least, followed up on this request, reporting to 3 Brigade Headquarters that the Hertz vehicle had been rented by an individual who was staying in Omagh but normally resided at Ramsey in the Isle of Man. He could not return to the island until the following day (the first flight left at 1410 on 30 December).

The Isle of Man might seem like a curious location for loyalist activity or sympathies. But loyalist paramilitaries appear to have had some support on the island. According to research conducted by Iain Turner, paramilitaries would arrange weapons training on the island during Orange Order summer visits to the island. A loyalist suspected by the Irish police of having some involvement in the Dublin-Monaghan bombings in May 1974 was later ruled out by the RUC since he had an Isle of Man alibi.

I do not know the outcome of Wilkin’s investigations. A later intelligence report compiled by 3 Brigade repeated the original assumption that republicans were likely to be behind the attack, although a note on the assessment acknowledged that no such attack by the IRA on a catholic premises had been carried out by local republicans in the past. This was, it concluded, “the first major incident in the area”. No mention is made of Captain Wilkin’s enquiries and whether any attempt had been made to question suspect(s) seen in the Hertz car rented from Aldergrove. The names of individuals have been redacted, as have a lot of other details in the Ministry of Defence file I was given partial access to last year.

It is impossible to conclude that the bombing of Dundrum on 28 December 1972 was the work of loyalist paramilitaries. However, like the man with the missing fingers [name also redacted] identified by the British Army as driving the Clones bomb car on the same night, the bombing at Dundrum – the possible link between a bombing and a car rental company frequently used by loyalists during this period – leaves more unanswered questions. Was the suspect staying in Omagh with an address at the isle of Man ruled out of the police investigation? Was Dundrum the intended target or was the bomb originally destined for somewhere else? As the British government legislates to shut down criminal prosecutions for Troubles linked violence, the absence of answers to events that may be linked to attacks in the Republic of Ireland – where police investigations will remain open – means that the international dimension of the Troubles may be impossible for the British government to ignore.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply