April 11, 2021, by eburke

Who Bombed Clones?

On 11 April 2021 the Sunday Times published an article by security correspondent John Mooney on my research into the loyalist border campaign of 1972-1974. I previously wrote a piece for the Irish Times on new evidence into loyalist bombings available in archives in London. This was based on my journal article for Terrorism and Political Violence, published in April 2020. I later took part in an RTE documentary on the Belturbet bombing on 28 December 1972. As the Sunday Times reported, since that documentary was broadcast, I have acquired new material relating to the bombing in the town of Clones, County Monaghan, on the same night.

Who bombed Clones?

48 years ago, on the night of 28 December 1972, the Luxor cinema on Fermanagh Street in the Monaghan border town of Clones was showing A Fistful of Dynamite. At the critical point of the film, when the film’s hero, an Irish republican explosives expert turned Mexican insurgent, is about to blow a bridge, an explosion thumped the cinema. The Luxor’s proprietor later described how he was thrown to the ground by the “real blast” and hit by falling glass.

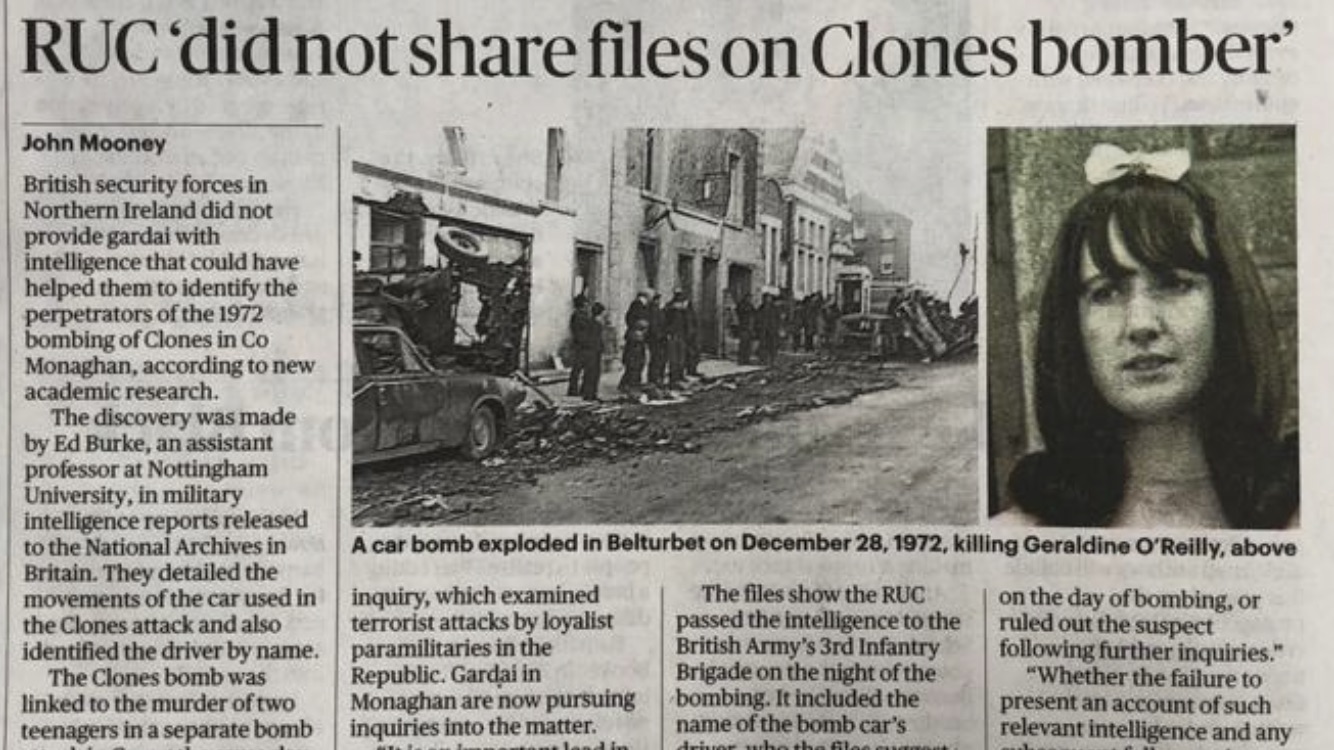

Patrons of the Luxor emerged to a scene of chaos. Dislodged electrical wires crackled above the dark, smoke-filled street. The sounds of screams, shouts and sirens were interrupted by the crump of debris falling from overhanging buildings. Narrow, steep Fermanagh Street acted as a funnel for the explosion. Residents of the village of Newbliss nearly five miles away felt the shockwaves of the blast.

Fermanagh Street, Clones, the day after the bombing

Two men were injured in the explosion; Luke McKiernan and Brendan Clancy were about to leave the Venice Café when they were blown back into the restaurant, suffering severe wounds to their legs. Local doctors and paramedics treated a number of other people injured by falling mortar and glass. Helen Donaghy was feeding her baby in a house on the street when the bomb exploded; doctors later removed a fragment of glass from her baby’s eye. Part of the axle of the bomb car was later discovered in a room at the back of a house.

Unlike the loyalist bomb the same night at nearby Belturbet in County Cavan – where teenagers Paddy Stanley and Geraldine O’Reilly died – nobody was killed in the Clones attack. The absence of fatalities in Clones (and in the other loyalist bomb on 28 December at Brittons’ pub near Pettigo in County Donegal) was by chance rather than design. In all three incidents loyalist paramilitaries placed a bomb in a busy area. This was indiscriminate, no-warning terrorism.

Businesses on Fermanagh Street – the commercial heart of Clones – were badly damaged and faced a long wait for for compensation before reopening. Some never recovered and closed for good. This was a time of repeated loyalist bombs in the Clones area – eight attacks took place between October 1972 and January 1974. Clones had already lost much of its County Fermanagh trade due to the cratering of roads and violence along the border. Now some County Monaghan customers also began to question whether it was safer to shop elsewhere.

Is there any intelligence that could identify those who placed the bomb in Clones? A 2004 report commissioned by the Irish government into bombings in the Irish state in the 1970s (chaired by Mr Justice Henry Barron) named Enniskillen loyalist Robert Bridge as the lead suspect. Part of Barron’s rationale for singling out Bridge, who was convicted of a sectarian murder in Fermanagh, was “… the absence of any intelligence pointing to other groups or individuals.”

But such intelligence did exist. Ministry of Defence intelligence files in the UK National Archives indicate that the British Army and the RUC concluded in March 1973 that Billy McMurray, an Ulster Defence Association (UDA) commander, was a lead suspect when it came to the planning and execution of bombings in the Irish state during December 1972 and January 1973.

Originally from Newtownabbey in County Antrim, 36 years old McMurray was in County Fermanagh during late 1972 and early 1973. British Army and RUC intelligence reporting from the time claimed that McMurray led an UDA Commando unit responsible for cross-border attacks. One such report claimed that McMurray was an associate of Bridge, although the former was evidently regarded as the more senior and dangerous of the two. Five people died as a result of loyalist bombings in the Irish state between December 1972 and January 1973, including two children at Belturbet. Nearly 200 people were injured, some very seriously – mostly in the Dublin bombing of 1 December 1972 in which two people were killed.

McMurray later confirmed in a court appearance in Belfast on 16 May 1973, where he appeared on an arms charge, that he was the UDA Headquarters officer responsible for Fermanagh and Tyrone – a statement that was reported in the Belfast Telegraph the following day. Although a plumber by trade, McMurray had a history of involvement in criminality and paramilitary organisations. He was first convicted of housebreaking and robbery in 1964, where he appeared in court alongside 19 years old Sammy Duddy, then with an address in the Rathcoole/Newtownabbey area and later a well-known figure in the UDA.

The Ulster Defence Association

The operation to target three disparate locations on the same night would have been carried out by a group of loyalists, rather than simply two or three individuals. The Barron Inquiry noted that the bomb car for Clones – a blue Morris (Austin) 1100, registration number 431 LZ – was stolen from Quay Lane car park in Enniskillen town centre between 6.20 and 7.35 pm on the night of the bombings. The Inquiry was unable to locate the Garda investigation file into the Clones bombing. However, Barron did review Garda C3 (Security and intelligence) files and concluded that, “From the Garda reports seen by the Inquiry it would appear that no one else remembered seeing the car between then and the time it exploded in Clones.”

Last year I submitted a Freedom of Information (FOI) Request for relevant Ministry of Defence (MOD) files which could shed some light on the attacks on 28 December 1972. The request was partially successful. What is revealed in the newly available Ministry of Defence documents is that on the night of 28 December 1972, before the bombings south of the border, the RUC believed that they knew who was driving a blue Morris (Austin) 1100 that had been reported stolen in Enniskillen. Although the registration is redacted in the MOD file, it seems likely that this is the same stolen blue Morris that was parked with an estimated 100 lbs of explosives in the boot on Fermanagh Street, before the bomb detonated at 10.01 pm.

Soldiers from 1st Battalion, The Staffordshire Regiment

Shortly after the theft of the blue Morris car in Enniskillen, the RUC told the headquarters of 1st Battalion, The Staffordshire Regiment – deployed in and around Portadown, Lurgan and Dungannon (Armagh and East Tyrone) – that they had intelligence on the identity of the man who now had possession of the car. The Staffordshire Regiment passed this information to 3rd Infantry Brigade Headquarters, who made the following entry in the brigade log at 9.45 pm, 16 minutes before the explosion in Clones, “From the RUC. A car stolen from Enniskillen, a Blue Morris Reg No [REDACTED] is thought to be driven by [REDACTED] he has lost some of his finders [sic] from his left hand. Thought to be heading towards Dungannon.” At the same time a note was also made in the log that 16th/5th The Queen’s Royal Lancers – the British Army unit responsible for security in County Fermanagh – had already been informed of this intelligence.

Instead of continuing on to Dungannon, at some point the bomb car turned right, towards nearby County Monaghan and its final destination of Clones. Like the intelligence on Billy McMurray, this information does not appear to have been passed on to Gardaí or, three decades later, to Barron. It is unclear why not.

Whether Gardaí in Clones would have responded in time on the evening of 28 December if they had intelligence on the stolen car and its driver – available in advance of the bombing – is also uncertain. 1972 was an exceptionally busy, dangerous period; there were significant political tensions and resentment in both states when it came to cross-border intelligence cooperation. Four days after the Clones bombing the Garda Chief Superintendent in Monaghan, J.P. McMahon reported that the Gardaí’s main problem in countering loyalist attacks was “almost a complete absence of information on members of extreme Protestant organisations in Northern Ireland and the identity of vehicles used by them.”

In January 1973 Lieutenant Colonel Anthony Millen at the British Army’s Headquarters Northern Ireland correctly anticipated that loyalist cross-border bombings would precipitate a more robust approach by the Irish government to border security, which would serve to further restrict republican operations as well as those by loyalist paramilitaries. Like Millen, many in the British Army and the RUC were frustrated with what they regarded as a lax, if not occasionally obstructionist, Irish approach to border security.

In the early 1970s arrangements for the swift exchange of intelligence between the RUC and An Garda Siochána had some way to go. Nevertheless, nearly 50 years later we still do not know if the man with the missing fingers on his left hand believed to be driving out of Enniskillen in a stolen blue Morris car on 28 December 1972 was ever questioned or ruled out of enquiries into the Clones bombing.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply