February 12, 2021, by eburke

Kafka, Cavan and the Departure of the Middlesex Regiment from Ireland in 1922

The diary entry of Franz Kafka on 2 August 1914 – “Germany has declared war on Russia, went swimming in the afternoon” – captures the tendency of the prosaic to intrude on moments of real historical significance. For the 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, headquartered at Cootehill, County Cavan, the arrival of the partition of Ireland was greeted with relief, if not delight. There had been few opportunities for sport in Cavan; the battalion could not find enough flat or dry ground in “drumlin country” in which to make a cricket crease. The ‘Die Hards’ had had enough.

Shortly after their departure from Cavan for Silesia, another European frontier zone, the officers of 1 Middlesex offered their rather caustic opinion of south Ulster in their regimental journal,

There are more comfortable places in the world than disused workhouses, and more interesting places than County Cavan, where to use an “Irishism”, if there had been a flat acre of ground for games it would have been a bog – and it was, therefore with few regrets that orders were received, late in January, to move to Gravesend on the 31st, en route for the Rhine. On that date the Battalion, 640 strong, concentrated at the North Wall, Dublin, where it embarked on the L & N.W. Railway Company’s boat Rathmore. The quay was left at 3 p.m., the band playing ‘Rule Britannia’. This had the effect of turning the dock labourers into ardent British patriots – until the band finished, that is … the Rhine had come to be looked upon as a kind of earthly paradise, and now the horse’s head was pointing in the right direction.

Such opinions on leaving Ireland – even though 1 Middlesex had only spent a year in the country and suffered few casualties – are echoed in other regimental journals for this period. The campaign in Ireland, according to the Middlesex Regiment’s Captain Brian Horrocks – subsequently the commander of XXX Corps during Operation Market Garden in 1944 – was an “unpleasant sort of warfare”. His time in Cavan is lumped together in a short paragraph in his autobiography with a discussion of the Middlesex Regiment’s mobilisation during the coal miners’ dispute of 1920.

Horrocks says nothing about his close friend, Captain Eric Dorman-Smith of the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers, the son of Edward Dorman-Smith, a local landowner at Cootehill and high sheriff of County Cavan, even though part of D Company, 1 Middlesex, appear to have been camped at the family estate in Bellamont Forest. This was a difficult period for Dorman-Smith, who served with his own regiment in Carlow and Kilkenny during the Anglo-Irish War of 1919-1921. Dorman-Smith was angered by RIC reprisals in his native Cootehill. On discovering that his former nurse at Bellamont was storing arms for the IRA, Dorman-Smith helped her to bury them in the estate, rather than turning her in.

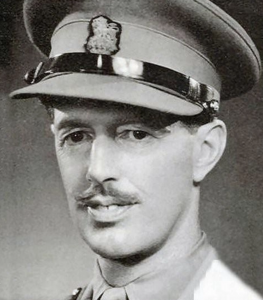

Brigadier Eric Dorman-Smith

Dorman-Smith was a brilliant officer, one of the few in the British Army who understood the full potential of armoured warfare at the outset of the Second World War. He was later credited with playing a central role in planning the Allied counter-offensive in North Africa in 1942 that pushed back Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s forces. Unyielding in his views about the failings of the British Army, Brigadier Dorman-Smith fell out of favour with his superiors (and Prime Minister Winston Churchill) and was removed from North Africa. In retirement he changed his surname to Dorman O’Gowan and became an adviser to the IRA during the early years of the Border Campaign, 1956-1962, holding training and planning meetings in Bellamont.

Bellamont Forest

Other members of the gentry in Cootehill were much less conflicted about their loyalties than Captain Dorman-Smith. Elizabeth Adams lived at Drumelton House, southwest of the town; her father had also been the High Sheriff of Cavan and her brother was an officer in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. In her later application for compensation from the British government (through the Irish Grants Committee), Adams noted that her family were proudly “protestant and loyalist”. Adams, although living at home with her invalid mother, increased rather than lowered her demonstrations of loyalty from 1918 to 1922. She frequently few the Union Jack from her house and entertained officers from the Middlesex Regiment. She claimed that Captain Geoffrey W. Kempster, the battalion intelligence officer, could vouch for the assistance she had given during these years. For Adams, the soldiers’ departure was a disaster – although she mistakenly recalls the departure taking place two months later, “…we were handed over into the power of our enemies by the British government on April 1 1922”. In June 1922 Adams was briefly imprisoned on a charge of firing on members of the new National Army (she was later released, and the charges dropped).

The response of the local regiment, the Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria’s), to partition was predictably one of intense alarm. The Faughs recruited in Cavan and Monaghan as well as in neighbouring northern counties. For a period, the regiment faced the threat of disbandment. The officers appear to have been so outraged at recent events in Ireland that the opening paragraphs of the January 1922 editorial in their journal, the Faugh a Ballagh were blacked out by the censor in London. Serving and retired men of the regiment had been targeted during the past two years and some killed.

In July 1921, the Faughs’ journal recorded that a few weeks earlier, “Major W[illiam] Stewart, 3rd Battalion, had has his house, Daily Hill, Clogher, burned to the ground by that curse of Ireland, the Sinn Féin organisation. Major Stewart was condemned to be shot, but the men left behind to do the work were rather saner than their fellows and refused to carry out their orders.” (the Stewarts were attacked by IRA volunteers from Scotstown Battalion, 1 Brigade, 5th Northern Division). The Royal Irish Fusiliers survived the sharp blow of partition and were later involved in intense fighting in Italy during 1943 and 1944, before being amalgamated with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers and Royal Ulster Rifles in 1968 to become the Royal Irish Rangers (and ultimately the Royal Irish Regiment).

The lack of sentiment among the Middlesex Regiment following the rupture of the United Kingdom – leaving behind a vulnerable population, not least those Ulster loyalists who found themselves on the wrong side of the border – is perhaps reflective of the attitude of phlegmatic professional soldiers off to police a different part of Europe or empire. No mention is made of Elizabeth Adams or other Ulster loyalists in Cavan by the departing Englishmen.

Sentiment was wasted energy – what mattered were better billets, good sport, fit men and an enemy you could find. Captain Horrocks and many other young English officers showed little appreciation that this “unpleasant” business in Ireland was for others in the British Army, not least the Irish regiments, a moment of existential crisis. In the summer of 1922, a la Kafka and his swimming appointment, a grateful Middlesex Regiment found that the flat valleys of Silesia were far more amenable than Cavan for the construction of a cricket crease.

I was fortunate in August 2019 to visit Bellamont with Brigadier Dorman O’Gowan’s grandson, Charles Dorman O’Gowan, a much-respected International Committee of the Red Cross representative in Afghanistan, with whom I first came into contact with eight years previously. I am grateful to him and his daughter for showing me their ancestral home. I am also thankful for the hospitality and courtesy shown to me by Caroline Corvan, veterans and volunteers at the Royal Irish Fusiliers Museum in Armagh during a recent research visit.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply