January 17, 2014, by Eve

I can resist anything except an invitation to a play

Last Monday, I was invited to a rehearsed reading of a new play by C.J. Wilmann. He is not, despite the name, an eccentric thespian who smokes a pipe and calls everyone ‘darling’. He’s just a nice, lovely fellow who happens to be a rather talented writer with a rather large man-crush on Oscar Wilde. In first year, I was incredibly fortunate to be cast in Mr Wilmann’s first full-length play, ‘Innocent Infidelity’, which he wrote in his final year studying English.

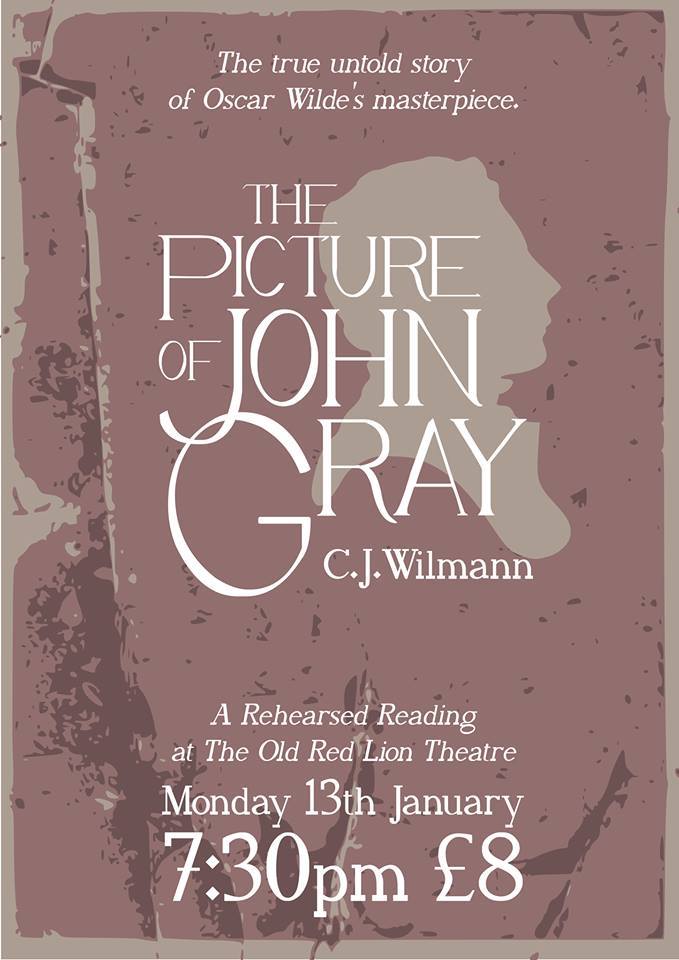

Two years on and Mr Wilmann has dropped the petty plot-lines of madness, adultery and casual poetry-endured murder. His new play ‘The Picture of John Gray’ deals with sexuality, human identity and the impossibility of defining love – and he throws in a peppering of death and religion – the classic Big Ones all serious young writers enjoy wrestling with.

The reading was performed in a very grimy and – apparently – very famous pub/theatre: the Old Red Lion Pub Theatre. Two minutes in I had completely forgot about the scripts – the minimal movement did not matter much as it was a predominantly sitting-and-talking type of play (as some many of Wilde’s own are). I was utterly engaged and immersed in the characters and the story.

I fell in love with Charles and Charles– the most constant example of love throughout the play – their dialogue was sweet, funny and – above all – charmingly honest. They were certainly the most likeable characters in the play.

Despite being the title character, John Gray was the character most alienated from the audience. I never seemed to know him as intimately as the Charleses or form a definite opinion of his character: he was arrogant, naïve, disdainful, playful, grimly determined. But you never knew what he was really thinking. Gray’s isolation from the audience was not a flaw – it draw attention to his complexity, he was an illustration of a difficult and muddled human being. And, our incomplete picture of him, served also to reflect his own confused image of his identity.

Yet an aspect of Gray’s character which I felt jarred awkwardly with his general persona was his flirtatious imitations of Raffalovich’s accent. In theory, on paper, I can imagine these moments to be fairly cute but in practice, on foot (so to speak), they were a bit bizarre. Ending the play on such a line did not work. This awkwardness may be averted with a different portrayal but I am not yet convinced.

The pace and style of the piece – namely, sitting-and-talking – worked well. I was never bored by the endless chatter but I felt that this was defiantly the unedited version and it does need shortened. It was particularly long even without the added time of deliberate movement and scenes changes. I think editing attention should be directed towards the Shelley’s going-to-give-evidence-maybe scene, which could have been tightened up to pinpoint its dangerous significance, and the hot air balloon scene, which had a distinctly uncertain climatic arch (up and down then up again) and could have pushed the narrative on much quicker.

A difficult issue with a play built on facts is how far the playwright assumes the audience’s prior knowledge of these facts. I hope that anyone who chooses to see a play called ‘The Picture of John Gray’ will note the allusion and will have at least a limited knowledge of Oscar Wilde. The first scene struggled with this issue. As someone who has read ‘Dorian Gray’ I was assumed by their references to who-was-who and this knowledge gave me a quick insight into the general personalities of these characters. I then felt slightly patronised (although this is maybe too strong a word) when the characters so explicitly spelt out what they were talking about. But I am well aware that we do not all come to the theatre with the same knowledge and this explanation was necessary. Perhaps I am simply harping on about this because of my hatred of scripts which consciously add highly unnatural lines simply to enlighten the audience – there was very, very little of this in the overall play; conversations flowed with a natural ease.

I was touched by the play – its simplicity of plot and complexity of content – and left in a sympathetic mood. I do not think it was a happy ending – it was not really an ending at all – their muddled lives continued after I felt the theatre. The underlying mood of fear and caution had not been destroyed and the play ended with the image of the second love, still shamed into silence.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply