December 16, 2020, by Emma Lowry

Why its important to ventilate indoors this Christmas to reduce the spread of Covid-19

Dr Ben Jones is Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture and Built Environment. He recently contributed to a SAGE Environmental and Modelling Group report on the role of ventilation in controlling SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The research found that being in a room ventilated with fresh air can reduce the risk of infection from coronavirus particles by over 70 per cent. Dr Jones also contributed to the understanding of respiratory carbon dioxide as an indicator of exposure risk as well as other ventilation interventions. These findings subsequently influenced the UK Government’s Covid-19 response. They also made headlines in the national media, advising us how to keep the virus at bay this Christmas.

In this post, Dr Jones talks to Emma Lowry about his research – the significance of which was formally acknowledged in a letter from the Government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance.

Dr Jones, can you tell us how your research featured in the SAGE report?

I contributed to the development of a mathematical model and statistical framework to estimate the number of virus copies that a susceptible person might inhale while in a particular building with an infected person. Because so much about the virus was unknown, and still is, we developed an index that allowed us to ignore what we don’t know and still say that scenario A is less/more safe than scenario B if the same infector was present in both scenarios.

This was used by SAGE to compare the relative risk of a range of scenarios as a function of ventilation provision. This advice has then been distilled by others to provide general advice to the public during the pandemic.

How did you get interested in this field?

I’ve been interested in the ventilation of buildings and the quality of indoor air for past 15 years. Recently, I had been looking at the emission of fine particles from the cooking of foods. It is not a huge step to move from modelling particles to virus-laden aerosols.

Why is it an important area of study?

Indoor air quality and building ventilation affects all of us. It is important to me because a single, simple intervention made to a significant number of buildings can positively affect the health of a population. Both my work on cooking and on the SARS-CoV-2 virus could save lives. However, the cooking work will have an effect in 30 to 40 years’ time (the health effects occur after continuous exposure over a long period of time and so there is a lag), whereas the virus work will have an immediate effect.

How did your involvement in the SAGE report come about?

There aren’t many researchers of building ventilation and indoor air quality in the UK and so we all know each other and talk regularly. When the airborne transmission of the virus was first hypothesised, we decided to get ahead and consider the problem by working together. One senior colleague was appointed to SAGE and another was appointed to the SAGE Environmental Modelling Group (EMG). I was asked by them to contribute to an EMG report on Role of Ventilation in Controlling SARS-CoV-2 Transmission that has been used by SAGE to support their advice.

How did your findings feature in the report?

Our model and assessment of relative risks of indoor scenarios was written up as a paper. It was referenced and a key plot was reproduced of relative risks for different scenarios, such as a day spent in a school classroom or office; and a one-hour visit to a supermarket or gym.

What was the outcome of the report being published?

I understand that the report has been used to support best practice guidance on the ventilation and occupancy of buildings by organisations like the Health and Safety Executive and the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers. It has also been picked up by at least six newspapers and magazines.

How do you hope it will make a difference in light of the Covid-19 pandemic?

I hope it is part of a series of measures that help to save lives. It should makes people think about how they ventilate indoor spaces in winter, which has always been a problem, even before the pandemic. I also hope that it means we’re more prepared when the next pandemic strikes.

Why is it particularly important to keep rooms ventilated in winter and perhaps most importantly at Christmas?

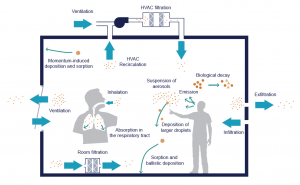

Coronavirus is spread through the air by droplets and smaller particles (known as aerosols) that are exhaled from the nose and mouth of an infected person as they breathe, speak or cough. They behave in a similar way to smoke but are invisible. The majority of virus transmissions happen indoors. Being indoors, with no fresh air, the particles can remain suspended in the air for hours and build up over time.

In the winter, we tend to seal up our buildings to keep them warm and save energy. However, this allows harmful contaminants to build up in the atmosphere if we don’t dilute them with fresh air. The longer people spend in the same room as these particles, the more likely they are to become infected. So Christmas time, when we are celebrating with loved ones at home, makes airborne transmission of the virus a significant risk, particularly from exhaled puffs of breath. This is why it is better to stay in our bubbles.

What should people do to minimise the risk?

Airing rooms is important as it reduces the number of infectious aerosols in the air. Simple actions like opening windows regularly throughout the day, especially when you share a space with others, and making sure that mechanical ventilation systems and kitchen and bathroom extractor fans are used correctly, will reduce your risk.

What are your next steps, research-wise?

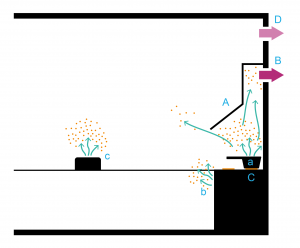

It’s back to cooking for me! I have a share of £1m of funding with colleagues from York and Chester to investigate the impacts of cooking and cleaning on indoor air quality in homes. We recently did a theoretical exploration of the use of kitchen ventilation and found that using the cooker hood for the cooking period plus 10 minutes afterwards has a large effect on the quality of air in a kitchen. This was included in a Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health report on the health effects of indoor air quality on children and young people along with several other recommendation.

Emissions are greater when browning foods, especially when fats are involved. So, frying or roasting meats will emit fine particles which are carcinogens that can cause cancer. These pollutants mix well in the kitchen air and can then be transported to other rooms of a house, so ventilate well and close the kitchen door.

My advice is: always switch on an extractor fan whenever the hob or oven are in use or when heating a pyrolytic oven to self-clean. If you don’t have a fan, open a nearby window or back door.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply