December 3, 2020, by Emma Lowry

Trio of aspiring Nottingham architects triumph in national Home of 2030 design competition

Three of our most talented fledgling architects were recently shortlisted for a Government-backed competition to design new ‘homes fit for the future’ for their socially-minded concepts that tackle loneliness and food insecurity.

The Home of 2030 contest asked students from across the UK for affordable, high-quality, low-carbon and age-friendly housing concepts in its Young Persons’ Design Challenge.

In total, three exciting and socially-responsible proposals by University of Nottingham undergraduates, Ella Rogers, Rachael Milliner and Henri Kopra made the grade. Rachael Milliner went on to scoop the 18-25 year old category and win the overall of the Design Challenge.

The trio graduated this summer from the Department of Architecture and Built Environment and all studied together on the Unit 5A design studio module: ‘Sustainable Communities’.

Their designs were inspired by what they learnt from a Unit 5A design studio project: 100 years of Council Housing, which celebrated the centenary of the Addison Act which first enshrined the building of new council “homes fit for heroes” after soldiers returned from World War I often to substandard slums.

During the course of 2019/20, Henri, Rachael and Ella were among the Unit 5A students, who worked with Nottingham City homes and a dozen residents on collaborative projects that explored the meaning of sustainable communities. The experience debunked preconceptions among the student cohort of what it means to be a council housing tenant and served as an eye-opener of how important housing design with a social benefit can be to society and architectural practice.

For the Homes of 2030 challenge, the shortlisted trio each submitted a project they had developed on their Unit 5A course. This was a housing design that could solve a real-life issue affecting a community; in this case redundant car garages in The Meadows. Residents often complain that these abandoned storage sites are an eyesore and magnet for antisocial behaviour and were enthusiastic to see how their purpose could be reimagined in a progressive way that would reflect the strong community spirit of The Meadows.

Ella came up with co-housing for older women to tackle the growing issue of loneliness – where residents who live alone can socialise together and support one another while retaining privacy and independence; while Henri imagined a safe and positive housing environment that fostered a community support network for single parents and their children. Rachael, meanwhile, focused on an urban farm at the heart of her co-living housing design, providing sustainable access to healthy food and shared community goals.

- Ella Rogers, , runner up in the 18-25 years category of the Young Persons’ Design Challenge in the Home of 2030 Awards

- A view from one of the three courtyards, offering up allotment spaces to be shared with the wider community.

- Visualising social communal spaces; social isolation is reduced by providing consistent opportunity for the women to engage passively or actively in neighbourly activity.

- Aerial view of The Meadows’ Older Women’s Co-Housing scheme highlighting some key design themes.

- Rachael Milliner, winner of the Young Persons Design Challenge in the Home of 2030 Awards

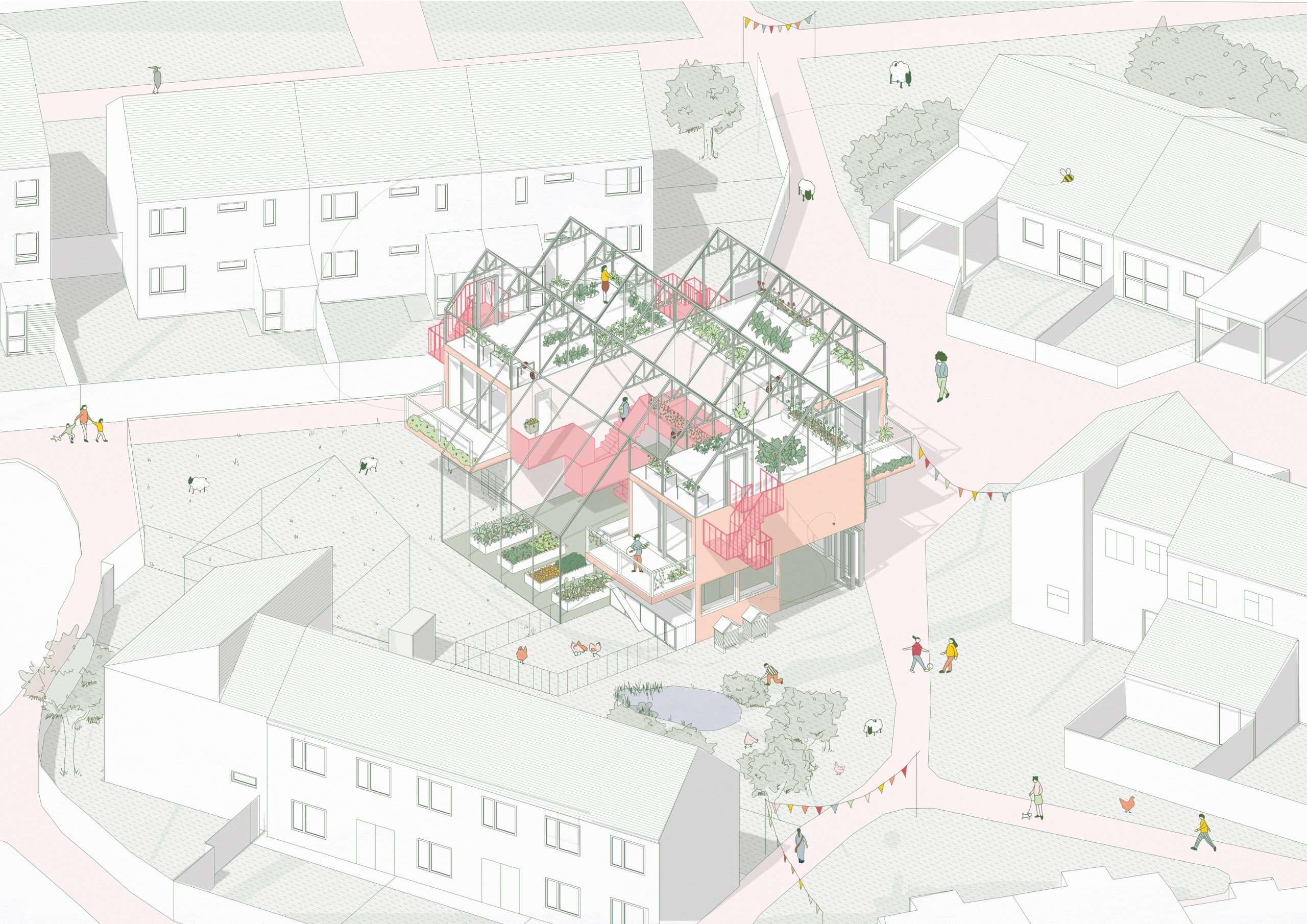

- Axonometric view of ‘Urban Co-Existing’ a densification scheme in the Meadows Nottingham exploring co-living, sustainable design and urban farming.

- Internal view of a farm to table day with the whole community. Demographics of humans and animals in the scheme.

- Home of 2030 finalist Henri Kopra

Perhaps another indication of just how profoundly their social housing research influenced them; all three nominees decided together that if any one of them were to win they would donate a proportion of any prize monies to the Grenfell Foundation to support those affected by the fire in 2017.

Ella, 22, is from Rugby in Warwickshire. She chose to study at Nottingham for its focus on real-life project, involving local communities which gave “tangibility to all of our designs and made the subject and impact of Architecture an exciting prospect for a career path”. Now graduated, she is working full-time in a Birmingham architect’s practice as part of her training to become a qualified architect.

Henri, 23, and from Tallinn, Estonia, came to Nottingham for its strong reputation in architecture and world class sporting opportunities, having practised fencing since he was eight-years-old. He graduated with a BArch Architecture (Hons) in summer 2020. He is currently working as an Architectural Assistant in Cullinan Studio, London and would like to go on to specialise in house designs that “challenge the status quo of private interest and capital gains overruling public need”.

Rachael, 23, from Bristol, UK, chose to study at Nottingham because it was one of the few universities offering a dual accredited Architecture and Engineering Course and is well-known for sustainable design. After completing her fourth and final year of the Architecture and Environmental Design MEng, she is now on an internship at Jan Braker Architects in Hamburg.

Here they talk about their nominated projects and the inspiration behind them.

Congratulations on reaching the final of such a high-profile competition. How did the 100 Years of Council Housing project inspire you? What did you learn from it?

HK: By researching council housing, I was able to learn about the wider political processes affecting architecture and this has inspired me to not just train to become an architect, but to expand my knowledge in, and collaborate with, all related fields in order to understand policies that govern life, and to stand against those that could bring environmental or social harm in the future, as exemplified by “Right to Buy”, and other neoliberal policies in the 1980s.

RM: When the opportunity came to do the 100 Years of Council Housing project I was thrilled as my research studies have been in the areas housing and the housing crisis. The biggest inspiration was the bold moves people have been willing to take to overcome crisis in public welfare – to quote the author Chris Matthews council housing provided the “biggest collective leap in living standards in British history”. I think an important take away from the project is how undeniable the link between housing and politics. Right to Buy and Neoliberal policies trace directly to the housing crisis we are in today but bold moves of the past give precedent to a challenge of the status quo needed today.

ER: The anniversary of the Addison Act provided us with an opportunity to celebrate everything that the different generations of council housing have achieved across the last 100 years. It highlighted to us the successes and failures of some of the key architectural ideas of the 20th Century: from the inter-war garden city movement, to post-war, high-rise system building with its high-density, low-rise reaction. This provided me with the inspiration to look forward and examine different approaches the built environment can take to ensure that secure, happy and healthy home environments can be delivered to future generations.

What drew you to solve the problem you did in your submitted project?

HK: A large demographic in need of social housing is single parents. In Nottingham, a third of all homelessness cases is made up of this demographic. My project aims to investigate how lone parents and their children could be supported better by environments that enable a community spirit by creating a free, playful, and inspiring environment.

RM: Urban farming can be a catalyst for social and environmental regeneration evidenced in; Detroit, USA; Havana, Cuba and many more cities globally. My interest in urban farming explores how retrospective bottom-up integration of polycultural urban farming – sitting at the intersection of design, green infrastructure and community engagement – has the potential of making cities more resilient against socio-environmental issues. In the 21st century the nuclear family model is no longer the only norm. Independence of women, increase in divorce and single living have led to a change in family structures. We have seen mass change in most aspects of human living and yet on the whole our housing has remained static. Co-living is just one alternative. Not a new way of living but is seeing a deliberate resurgence in interest due to its benefits; resource sharing, community, reduced living costs and possibilities for design input.

ER: I had the pleasure of meeting several past and present residents from the Meadows who spoke so positively of their time living on the estate. However, the development, like many others across the country, consists largely of nuclear family homes and fails to cater for the needs of older generations. A concern expressed to me repeatedly was the lack of alternatives, and so it was time to consider atypical solutions. My hope is that continual development of schemes such as mine will allow for more diverse, inclusive communities to reduce social isolation in the ageing population and other groups often overlooked.

How did your School support you in the competition process?

HK: Alison Davies was our tutor and not enough good can be said about her. She has been devoted to making sure we have the best learning experience not just academically, but by encouraging experimenting, making, learning from each other, and engaging with the wider world and disciplines.

ER: All our university mentors were amazing throughout the design process. Alongside the great influence from Nottingham City Homes, we were really encouraged to consider a client narrative to our schemes. For me, this was vital in smaller scale design decisions to make the spaces both liveable and loveable throughout the women’s daily routines.

Did lockdown restrictions change the competition process at all?

ER: I think the lockdown restrictions changed life for everybody in one way or another, but with regards to the competition, it made me reflect on the importance of the key ambitions of my design. We have all been made increasingly aware of the vulnerability of the elderly, particularly those living in isolation. But what if there was an alternative? We need to explore atypical housing models to cater for societal shifts and to develop housing that people are proud to call their homes and communities at all stages of life.

How did it feel to be shortlisted in this prestigious architecture award?

HK: Winning external awards, such as the RIBA Part 1 Bursary in my first year, have always motivated me to work even harder to prove that I am worthy of these opportunities. Winning this award would be especially important as it would recognise a demand currently not prioritised by the government and would assure me that I am not alone in a fight for a more equitable, socially and environmentally responsible future urbanism.

RM: While it is great to be commended for succeeding in something I am so passionate about, it will feel even better when schemes like all of those proposed for this competition are integrated into the fabric of our urban environment.

ER: I feel honoured to be chosen from such incredible entries. I am both excited and proud to be part of a collective of young designers/architects that feel passionate about addressing such important issues within society. I have loved being a part of an essential narrative of change for the architectural industry to address them.

How might such a win help you in your future studies/career?

RM: Even being in the final has opened doors I didn’t expect. Just over a month ago I was invited to a roundtable to advise on the Planning White Paper with the housing minister. For someone whose ambition is to contribute positive change to the housing situation in our country – it felt like a big achievement.

ER: I hope that it will demonstrate to future employers a real passion for what I do and an eagerness to create living environments which can strive to improve people’s quality of living. With the confidence of knowing that people have believed in my design potential, I know that this would encourage me to pursue a career delivering spaces with great social ambitions.

What style of architecture and industry figure inspires you most?

ER: Figures such as Peter Barber really inspire me. His work breaks the mould of standard affordable housing, creating unusual and innovative designs underpinned by strong social commitments and a desire to create beautiful home environments for all as a setting for happy and healthy lives.

RM: Socially and environmentally equitable architecture projects inspire me the most and the industry figures I admire are the ones who champion these schemes.

The first is Kate Macintosh, the architect of Dawsons Heights in Dulwich South London, in her late 20s worked for local authorities in the 60s designing humane buildings for the communities they served. Today she still campaigns for public welfare and social housing challenging architects and the government to be better. The second is Dong Ping Wong the founder of FOOD New York. His firm describes itself as an ‘environmental design studio’ and he has done work varying from homes for Kanye West to a community funded pool that will filter river water whilst allowing visitors to swim in the Manhattan river. Providing fun, productive architecture. During the events that have unfolded in 2020 first COVID and then the worldwide Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd he has used his standing in the community to amplify voices that need to be heard, call out members and firms in the architectural community failing and – with many others – offered services to support black members of the community. Wong is not alone in these actions however – for me – he is an example of what architects can and should strive to be.

HK: I am currently working as an Architectural Assistant in Cullinan Studio, a world-renowned employee-owned cooperative that has been practising architecture under the slogan “Architecture is a social act” since the 1960s. The strong social and environmental ethos of the practice has guided the architectural practice throughout the years, and regarding the climate crisis, the Studio advocates rethinking cities to make room for nature. This aligns with my personal interests and ethos, and I hope to continue making my contribution for these goals in the future, either here in the UK, or in Estonia.

What needs to change to increase the appetite for sustainable/green housing?

RM: Funding and policy needs to change so that it is more affordable and therefore a viable option for the everyday person. Currently sustainable housing is only accessible to those who can afford it but if you live in a properly insulated home, with solar panels that provide half your electricity, you will save money. We don’t have an issue of interest we have an issue of accessibility.

HK: With the facts we have today, there is no case for consciously choosing an unsustainable way of developing our environments for merely short-term capital gains. Moreover, it is clear that investing in ecological solutions will have a better capital return in the long run. Sustainability is not as difficult to achieve as we think, we simply need to be open to thinking in new ways and redefining our values. Raising awareness about the current major issues caused by our lifestyle based on consumerism, such as an economy that assumes perpetual growth on the account of exploiting the natural resources, could lead to a major shift in public thinking. When we start consuming less in quantity and more in quality, environmental and social problems will no longer be as difficult to solve.

ER: I think that more needs to be done for the climate emergency to be more widely recognised. This means educating people surrounding the immediate need for a more sustainable built environment and the potential that schemes such as Goldsmith Street hold in shaping a future generation of exciting and responsible architecture. This scheme proves to be an exemplar case of making sustainable housing accessible. There will be an increased appetite for green homes once their features are mainstreamed and their benefits are witnessed not just by a privileged minority. Celebrating and benchmarking results like these reflects the necessity of more conscious design choices and positively advertises the opportunity for people to become part of a global shift through the homes they choose to live in.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply