November 30, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

Calendar Adventures

Sometimes the simplest of questions are the most difficult to answer. In archives, that question can often be ‘what date is this document?’. Georgian/Julian calendars, regnal years, and feast days are all recognizable dating systems for people who use historic documents regularly (even if we do have to double check how to convert them into a ‘modern’ date).

Frontispiece of French periodical – ‘La Decade, No. 20′ including revolutionary dating (’20 Germinal’, i.e. mid-April) and beginning with an article entitled ‘Hygiene’. Ref: Dc 140 D46/Au6/20

But one calendar which we don’t often come across is the French Republican calendar. In some respects it’s a shame, because it’s interesting, logical and pretty, but on the other hand, society probably doesn’t need yet another way of marking the days. The calendar was created during the French Revolution was was only in use between 1793 and 1805, in France and territories under French rule. Having removed as much of the old royal and religious influence from government as possible, the revolutionaries tried to remove it from the calendar, and, having decimalised currency, decided to do it with time as well.

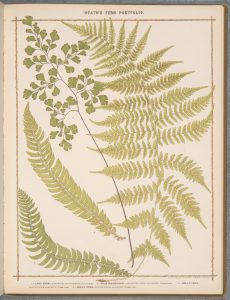

3 Floreal (22 April) was represented by ferns, and 28 Ventose (18 March) by the Maidenhair fern specifically. From Francis George Heath’s ‘The fern portfolio’, 1885

The Republican calendar year began in what was previously known as September, on the autumn equinox, and was divided into twelve months, each with three weeks, or décades, each lasting ten days. This gives only 360 days, the remaining five (or possibly six) weren’t allocated a month but were national holidays, allocated in the run-up to the new year.

25 Pluviôse (13 February), represented by a hare. From Thomas Bewick from ‘A General History of Quadrupeds’ by Ralph Beilby, 1807.

The months were given new names inspired by nature, for example ‘meadow’ (May to June), and the weather in Paris, which meant that some of the winter month names such as ‘snowy’ (December to January) and ‘frosty’ (February to March) probably weren’t all that reflective of life on the Mediterranean coast, and certainly weren’t for the French overseas territories.

Officially the 10 days of the week were numeric, which is boring but functional. However, about two thirds of French people were employed in agriculture, and the Revolution had, in part, been caused by problems with land concentrated in the hands of nobles and the Church, feudalism, and food shortages. Life for many French peasants improved as the estates were broken up and harvest taxes ended. To celebrate the rural economy and reflect its importance to the lives of French people, a new day-naming system was devised, which conveniently also had the effect of offering an alternative to the Catholic Church’s calendar of saints and feast days. One day each week was named after an agricultural tool, another a common animal, with the remaining eight named after the trees, flowers, and produce in that season. Also types of stone and minerals, because there’s not much to harvest in the ex-month of January except rocks.

The French government used the calendar on official documents, including on the Act that abolished it, signed on 22 Fructidor (Hazlenut) in the year XIII (or 9 September 1805). By this stage, other European countries had been gradually harmonising their calendars, and a decimalised calendar that began the year at a different point only caused confusion. The ten-day weeks proved unpopular amongst workers, who still only got one day off. And although the French state may have been secularised, the people who wanted to attend Church on Sundays and Holy Days found that their days off didn’t coincide. The authorities tweaked it, trying to appease grievances whilst keep the heart of the calendar, but a year after becoming Emperor of France Napoleon Bonaparte abolished the Revolutionary Calendar altogether and replaced it once more with the Gregorian calendar.

Manuscripts and Special Collections has over 3000 printed books and pamphlets in French Revolution Collection, which can be viewed in the Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus by appointment only. To book your seat, please email us at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk. For the latest information please follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott and read about our Covid-secure visitor procedures in our blog post.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply