December 17, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

A Tale of Scales and Slippers

Pantomime is as part of a British Christmas as mince pies, tinsel, and repeatedly losing the end of the sellotape when wrapping presents. Nottingham Playhouse‘s Christmas panto this year is Cinderella, and despite the novel presentation of On Demand performances and plans for socially-distanced theatre audiences, the storyline will remain comfortingly familiar.

The panto plot is different to the fairy tale, adapted as it is to incorporate audience interaction and more characters (there’s no Buttons in the fairy story or Disney film, for example), but even this follows the great tradition of adapting and revising so-called traditional tales.

The basic structure remains the same: orphaned and forced to work as a servant for her stepmother, Cinderella is transformed by her fairy godmother to allow her to go to a ball where a Prince falls in love with her. Cinderella loses a shoe in her rush to leave before the magic wears off at midnight. The Prince orders every woman to try on the shoe until he finds her.

In the original rags-to-riches story (technically, riches-to-rags-to-greater riches, as her family is not poor), at no stage does Cinderella confess her identity. There is the unstated implication that the Prince must fall in love with her in her degraded state. This does not mean she passively accepts her life of drudgery, although how resourceful she is varies in each retelling.

Some 700 versions of Cinderella have been found across the world. One of the earliest written tales to resemble the story, Yeh-hsien or Ye Xian, comes from China and is dated to c.850 AD. In this story, a talking fish with golden scales is the source of the magic, and Ye Xian wears tiny golden shoes to the ball. Though it may pre-date the practice of footbinding, it is theorised that it’s an early demonstration of the widespread admiration in China for small feet.

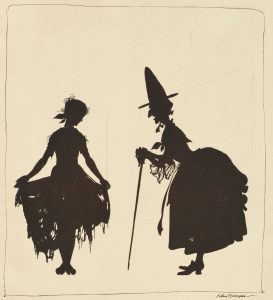

Illustration by Arthur Rackham for ‘Cinderella’ retold by C.S. Evans, from the Supplement to ‘The Bookman’, Christmas 1919

Cinderella is not always as good as she is beautiful. Some Middle-Eastern and early European versions, as recorded by the 17th century fairy tale collector Giambattista Basile, include the heroine plotting her stepmother’s murder. Other versions restrict any violent acts to the stepfamily, who suffer gruesome fates ranging from death by flying stones or boiling alive, which makes the Brothers Grimm’s punishment of having their eyes pecked out during Cinderella’s wedding seem comparatively merciful. The modern version where Cinderella forgives them or ‘only’ has them banished from the Kingdom reflects a change from fairy tales as morality stories for adults, to amusing children’s stories. I imagine it would also be quite difficult to get approval for a script with a gruesome blinded-by-birds scene in a light-hearted festive family show.

French author Charles Perrault’s version was the first to introduce a glass slipper. The clear, unmalleable material allowed the Prince to see if the shoe fitted. This is significant because other versions had either used a different object to prove her identity, or, if it was a slipper, Cinderella’s stepsisters cut off their toes to make the shoe fit. The only connection to real life is that in seventeenth-century France, the time Perrault wrote his version, 80% of widowers remarried within a year, making stepfamilies very common. With the wicked stepmother the primary villain, Cinderella’s father, who allows the abuse, recedes until he virtually disappears from the story and rarely receives any punishment for his actions or inactions.

‘Cinderella’ story from ‘Tales of passed times by Mother Goose with morals written in French by M. Perrault (1796)

Originally Cinderella was granted her wish to go to the ball by the spirit of her dead mother, in the form of a magical fish, cow, animal bones or a tree. The fairy godmother is a later addition, and one much more panto-friendly. And that’s why, whenever you next go to the panto, whatever other alterations they’ve made to the story, you can guarantee that the wish-granting entity will be covered in sequins and not scales.

The images here are taken from our Special Collections, most notably from the Briggs Collection of Children’s Literature. These are available to view by appointment in the Reading Room. Please check the website for up-to-date details about opening times. We also hold several archives relating to theatre and theatre companies, including a selection of theatre programmes and playscripts from Nottingham Playhouse. More details about the collections can be found in the online catalogue.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply