October 9, 2018, by Kathryn Summerwill

The Night Nottingham Castle Burned

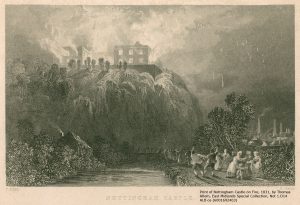

On the evening of Monday 10 October 1831, people gathered by the banks of the River Leen to watch the spectacular sight of Nottingham Castle, ablaze, sparks flying. The scene was captured by artist Thomas Allom and engraved by R. Sands. The mounted print, 25cm by 31cm in size, shows a pair of men dancing joyfully at the sight of the inferno. Why would this be?

Drawing of Nottingham Castle on fire, 1831, by Thomas Allom, engraved by R. Sands. East Midlands Special Collection Not 1.D14 ALB os (6001692403)

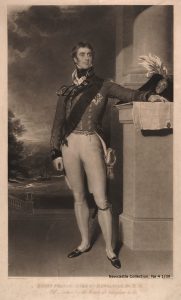

The answer lies with the owner of the castle at that time: Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne (1785-1851). The duke was a prominent opponent of parliamentary reform, and October 1831 was a highly-charged time. A Reform Bill intending to widen the franchise had passed the House of Commons, but on Saturday 8 October the House of Lords rejected it. The news reached Nottingham on Saturday evening. The High Sheriff of Nottingham, Thomas Moore, wrote to the duke and told him that the following day some shop windows were broken, but “the Mob dispersed on the appearance of the Military”. The Mayor called a public meeting at noon on Monday, which was attended peacefully; however, in the evening

“a Mob collected and after committing a few acts of outrage in the Town proceeded to Colwick where they destroyed the furniture & attempted to burn Mr Muster’s House, in which to a certain extent they succeeded. I regret to say that afterwards they proceeded to your Grace’s Castle which they completely destroyed” (Newcastle Collection, Ne C 5004).

The 4th Duke of Newcastle, engraved by Charles Turner and printed by Colnaghi, Son and Company. Newcastle Collection, Ne 4 1/39

Other people also wrote to the duke on the 11th. Thomas Winter of Red Hill told him “that the Castle was burnt to ruins during last night & that the Mob are deliberately pulling down the fence walls at this time…” (Newcastle Collection, Ne C 4999). John Sherbrooke Gell of Nottingham wrote that “the main walls alone of Nottingham Castle remain standing. The Mob made a breach in the Wall & also burst the Gate about six oClock last night, whilst I was at Colwick” (Newcastle Collection, Ne C 5000).

The duke was in the House of Lords when he received the news from the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne, on Tuesday 11th October.

“Ld Melbourne told me that he had very bad news from Nott’s – that Nottingham was in a shocking state & that the rioters had set fire to Nottm Castle – I have heard nothing about it, & I hope that it is not true, but I much fear that it is – The whole country is in a horrid & fearful state”. (Newcastle Collection, Ne 2 F 4/1, p.69)

The rioting in Nottingham was not an isolated incident. Disturbances also occurred in Bristol, London, Derby, Worcester and Bath. People were incensed that unelected peers could block the passage of reform. However, the political purpose of the gatherings in Nottingham degenerated into wanton destruction. The attack on Colwick Hall, the home of John Musters (who was not a politician), was particularly violent, taking place while his wife and daughter were at home.

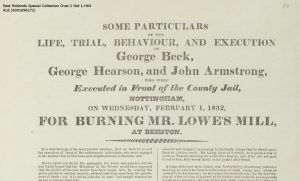

Broadside from ‘Nottinghamshire Trials’ volume, East Midlands Special Collection Over.X Not 1.H64 ALB

On Tuesday 12 October the Nottingham rioters gathered again, and marched to Beeston, where they set fire to a silk mill belonging to Mr Lowe. They attacked the gates of Wollaton Park, and marched back into Nottingham, but arrests were made and the crowd dispersed. A schedule of prisoners committed to trial (Newcastle Collection, Ne C 5052) lists the men indicted for the outrages. 26 men were tried at a Special Assize starting on 4 January 1832. George Beck, George Hearson and John Armstrong were executed for their part in setting fire to the mill in Beeston. However, no-one was ever convicted of setting fire to Nottingham Castle.

The schedule of prisoners is currently on display in the Weston Gallery as part of the exhibition A Selection of Elections, which runs until 2 December. The other documents appear in our online learning resource, Politics of the 4th Duke of Newcastle. They can also be viewed in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room. For more information about our holdings or exhibitions, follow us @mssUniNott or read our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply