September 28, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Mad Dogs & Englishmen

World Rabies Day takes place each year on September 28, the anniversary of the death of Louis Pasteur. Better known for developing the pasteurisation process, he was also involved with developing the first efficacious rabies vaccine.

It’s not a disease that many people in the UK have reason to give much thought to, but roughly 55,000 people worldwide die of rabies annually. This is probably an underestimate as most infections occur in poor, rural locations with few accessible healthcare facilities and even patchier record-keeping. Rabies is a viral infection causing inflammation of the brain and central nervous system. It has the highest mortality rate of any disease, at over 99.9%. In comparison, nineteenth century smallpox patients had a 30% mortality rate, and cholera sufferers had a 50% mortality rate. Even with the best modern medical care, the chances of surviving once symptoms appear are negligible. The tragedy is that, if administered quickly, the post-exposure prophylaxis treatment is 100% effective at preventing rabies deaths.

The symptoms are so horrifying that they have become deeply ingrained in popular culture. The term ‘hydrophobia’ was once used to refer to the disease in people (‘rabies’ for infected animals) after the most dramatic symptom in late-stage rabies. Early symptoms are much more generic: pain or tingling at the wound site, generally feeling unwell or melancholy, and disturbed sleep. The fever, aggressive delirium and foaming at the mouth follow a day or so later. The virus is transmitted through infected saliva, and so it both stimulates saliva production and causes painful spasms in the throat whenever the patient tries to swallow or drink.

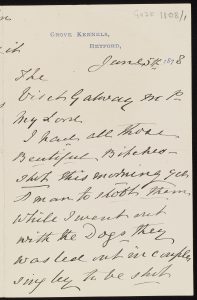

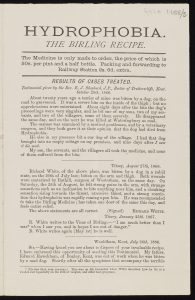

Letter from John Morgan to George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway, with enclosed recipe for the treatment of ‘Hydrophobia’ 5 June 1878. Ref: Ga 2 E 1108.

The letter opens with the writer expressing regret for having to shoot several bitches due to two cases of rabies at the kennels. Later correspondence showed that the sick dogs’ bedding was burned but that the rest of the animals appeared healthy. The advert enclosed with the letter, for Birling’s Hydrophobia recipe, is a list of testimonials from people who had used the medicine themselves or given it to their animals after a bite from a rabid dog. There is no mention of what is in the medicine.

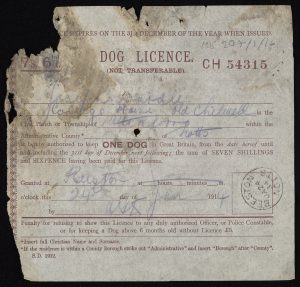

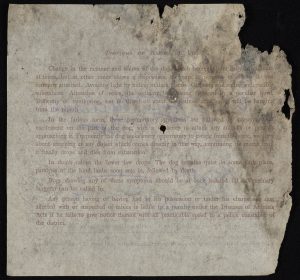

A dog licence for Joseph Wardle in College House Chilwell; 24 Jan 1914. Ref: MS 297/1/16.

The licence authorized Mr Wardle to keep one dog in Great Britain, after paying seven shillings and sixpence for the licence. The back of the licence lists the symptoms of rabies in dogs, and owners who suspected their dog was infected were required by law to inform the authorities immediately. Rabies is usually caught from the bite or scratch of an infected animal. Globally, dogs are the main source of human rabies deaths, contributing over 90% of all rabies transmissions to humans. Rabies poses a risk to people and animals on every continent, apart from Antarctica. The only reservoir in the UK is wild bats, with the most recent case of rabies identified in a bat in Great Britain was in July 2018. The risk is tiny, however, and there has been exactly one recorded UK case of transmission to a human via bats.

Bill from Messrs. Ward and Cox, sent to William Cavendish-Scott-Bentinck, 4th Duke of Portland; January 1818. Ref: Pw H 2136.

Not everyone who was (or is) bitten by a rabid animal contracts the disease, which is why some of the folk-cures seem to ‘work’. This is a bill for medical treatment given to Mr Skinner’s servant boy in Holbeck who was ‘bitten by a dog supposed to be mad’. Over the course of three weeks, various mixtures were applied to the wound, at a cost of 17s.9d. There’s no further documentation suggesting that the servant boy contracted rabies so he was probably lucky enough not to be infected in the first place, because the apothecary’s concoction would not have worked.

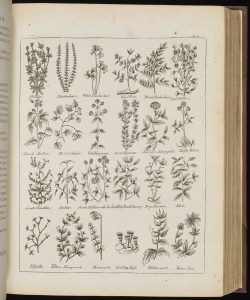

“Mint” from Culpeper’s ‘English physician and complete herbal’; Special Collection RS177.G7 CUL

There were plenty of useless home remedies to chose from, as is to be expected from a disease that has a recorded history stretching back 4000 years. These pages from a late-18th century edition of Nicholas Culpeper’s book informed readers that a tincture made with mint was an ‘infallible remedy’ for the bite of a mad dog. This best-selling volume contained descriptions and remedies for all sorts of ailments using hundreds of commonly available plants and was intended to help people unable to afford an apothecary. However, the recently-bitten with no access to mint had a choice of other remedies, as Culpeper also suggested garlic, pimpernel and nettles.

It goes without saying that the end result would be the same whichever remedy was chosen.

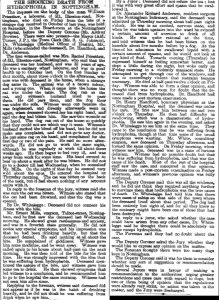

“The Shocking Death from Hydrophobia in Nottingham” Nottinghamshire Guardian; 11 February 1887.

This really ought not to have been a great shock to people in Nottingham. In 1886 there was a spate of rabid animals that attacked several people, causing understandable alarm. There was, however, hope: French scientists Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) and Émile Roux (1853-1933), developed the first successful rabies vaccination in 1885. The incubation period for rabies is usually 1–3 months, as the virus slowly travels from the bite site to the brain via the nerves. Even with the lengthy journey times of the 1880s, there was ample time for the Nottingham patients to receive treatment.

Unfortunately labourer William Priestlaw of Nottingham did not realise the seriousness of the bite to the hand he received. Four months later he died in Nottingham General Hospital, two days after admittance, of an indisputable case of rabies. At his inquest the jury expressed their dissatisfaction at the number of dogs in Nottingham, and the disregard for the muzzle regulations that had been put in place.

The original manuscripts and rare books are part of Manuscripts & Special Collections at The University of Nottingham. There are many accounts of diseases and home remedies mentioned in the personal and family papers here. We also hold hospital and health records, and medical texts in the Medical Rare Books Collection. More information about our holdings and the online catalogues is available from our website, by following us @mssUniNott and from our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply