March 10, 2014, by Kathryn Steenson

A Family Reunion

This is a guest post by Library Assistant Nicholas Blake.

I never expected to discover that my new place of work was home to an archive collection of my family’s documents dating back hundreds of years. It was only after I’d been interviewed for my library assistant post here at the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections that I learnt from my mother Catharine – whose maiden name is Chamier – that this was where the Papers of the Families of Chamier and Deschamps, 1623-1862, had been deposited.

The Chamiers were originally a French Huguenot family who fled to England in 1691 shortly after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes which had given rights and tolerance towards Protestants in France. A hundred years earlier a key founder of the Edict had been Daniel Chamier (c.1565-1621), who became – along with several of his descendants down the generations – minister of the Reformed Church at Montelimar. With religious intolerance no longer against the law and threats rife against non-Catholics, a hasty emigration to London was in order.

Once based in Protestant-friendly England the family was able to live peaceably again. One notable Chamier, Anthony (1725-1780), became a friend of Samuel Johnson (you may have read his seminal bestseller ‘The Dictionary’) and original member of his literary establishment and dining club ‘The Club’. Anthony’s sister, Judith Chamier, married a man named Jean Deschamps (1709-1767) who was himself a Huguenot and had only recently moved to England from Berlin where he had tutored the sons of King Frederick II of Prussia and argued philosophy with Voltaire. On the death of childless Anthony in 1780 the Chamier line should have ended, but Anthony had proposed that he would leave his fortune to his sister’s son provided he changed his name from Deschamps to Chamier. In need of money, the nephew accepted, thus cementing the connection between the Deschamps and the Chamiers and allowing the lineage to continue. All Chamiers you meet nowadays are therefore descended from John Ezekiel Chamier, née Deschamps.

My mother lost her Chamier name at marriage, but as there are so many strands of the family nowadays it seems unlikely my uncle will bequest his fortune to me if I change my name. My sister and I were both given ‘Chamier’ as a middle name, and having this distinctive French moniker, combined with memories of a big reunion in London in 1991 arranged by my grandmother Barbara Chamier to celebrate three hundred years since the Chamiers’ arrived in the UK, meant that I’ve always been aware of my connection to the family, even if I was initially ignorant of the collection here at the University.

The collection was, we believe, mostly compiled by Henry Chamier in the 1850s, and is made up of papers and journals relating to the aforementioned Daniel Chamier, Jean Deschamps, and other family articles and correspondence. It’s a mini treasure trove for anyone interested in the Huguenots and religious reformation, providing they can read centuries-old French. After being rediscovered after decades of languishing in a garage, the documents were passed on to my uncle, and the collection was deposited in the University of Nottingham archives in 1970 at the suggestion of my grandmother who was warden of Nightingale Hall at the time. Forty-three years later, unaware of the existence of the family papers, I started work here at Manuscripts and Special Collections.

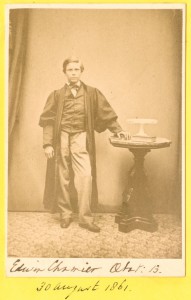

Catharine and Nicholas Blake examining their ancestor’s memoirs, which Mrs Blake donated to Manuscripts and Special Collections.

My mother recently came in to the department to present a newly acquired copy of a volume translating some of Daniel Chamier’s journal into English, Ref: Ca A 4 ‘Memoir of Daniel Chamier, minister of the Reformed Church with notices of his descendants’, 1852. This volume was authored by one of his descendants and rather grandiloquently declares in the preface that Daniel Chamier “has not only been styled the Soul the Organ and the Hero of his Party but the Defender the Apostle the Martyr of the Protestant Church of France”. Part memoir and part biography, the family papers formed the basis of the book’s research, and the collection is all the stronger for its inclusion. Learning about the Chamier collection has been a surprise and highlight of this job, and I’m delighted to not only be working with the people looking after it for future family members and researchers to view, but to have aided in some small way to its expansion.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply