February 17, 2014, by Kathryn Steenson

Rain, Records and Research

January has been declared the ‘wettest month since records began‘ in parts of Britain by the Met Office, with many towns in Wales, the South West and Home Counties flooded and facing yet more storms. Several thousand miles away, the USA shivered as the Polar Vortex brought temperatures as low as -26C, and at least nine states recorded their lowest temperatures ever.

But what are these ‘records’, when did they begin, and how reliable are they?

In the UK, the Met Office retains historic data from its weather stations across the country. It was established as the national weather service in 1854, originally as a service for sailors. How far back the data goes depends on when the weather station started recording, with the best coverage from the beginning of the twentieth century. The earliest monthly weather data available from the Met Office’s historic data webpage dates from 1853 and was recorded from stations in Armagh and Oxford – both of which are still operational.

These are not the only sources of historic weather information, and the records scattered across many different archives go back considerably earlier than the nineteenth century.

Photograph of technicians working with river flow model of the River Trent in Nottingham, c.1948 (Ref: RE/DOP/H36/39/1)

Over the next three years, academics from the Universities of Nottingham, Aberystwyth, Glasgow and Liverpool will be investigating extreme and unusual weather using historical records and oral histories. The project, ‘Spaces of Experience and Horizons of Expectation: the implications of extreme weather events, past, present and future’ is funded by the Arts & Humanities Research Council, and researchers have visited Manuscripts and Special Collections to look at our resources.

The major resource for weather research here are the 500-plus boxes of Water Records. The records span the seventeenth to the twentieth centuries, and until nationalisation, the supply, management and control of water resources was in the responsibility of a multitude of local autonomous bodies. The collection includes records of water levels, which, along with the minutes, maps, correspondence and reports, provide evidence about floods in the area, and the success or otherwise of the various drainage schemes. Photographs from the engineer’s department and files within the papers of hydrologist H.R. Potter show the efforts taken to collect evidence of the cause and effect of the devastating floods which periodically occurred, and document the work of the Authority in flood prevention. Potter used both historical records and experimental research to gather meteorological and hydrological data on extreme weather events. Data collected on rainfall, evaporation and river levels provide information on the changing environmental conditions in the catchment area.

Other weather records include A Collection of Meteorological Records for Nottinghamshire, 1841-1981 (Ref: Met). This is an artificial grouping of a number of small collections, largely created by amateur enthusiasts, researchers and students who maintained local weather stations.

The idea of using archive material to ascertain past weather is not a new one. This project is focussing on selected British regions, but over at citizen-science website Zooniverse, members of the public have been transcribing global ships’ log books and survey data for several years as part of the oldWeather project. A number of British and American archives, libraries and other institutions have collaborated with the scientists and records have come from sources as diverse as the English East India Company, British Royal Navy and United States Coast Guard.

The idea of using archive material to ascertain past weather is not a new one. This project is focussing on selected British regions, but over at citizen-science website Zooniverse, members of the public have been transcribing global ships’ log books and survey data for several years as part of the oldWeather project. A number of British and American archives, libraries and other institutions have collaborated with the scientists and records have come from sources as diverse as the English East India Company, British Royal Navy and United States Coast Guard.

The records cover the 1780s to the 1940s, and the amount of information is staggering – the Royal Navy log books alone yielded 1.6 million weather observations. Seventy per cent of the Earth’s surface is water, and the weather recordings come from all over the globe, from merchant ships sailing to China and South Africa, geographical survey ships in the Antarctic, and naval ships in the Atlantic.

The meteorological readings in the log books and company archives are useful for scientists because they are both long-running and accurate. Gaps exist where not every log book survives – shipwrecks, for example, and some stray log books that the collaborating organisations don’t have in their possession, such as the odd ones we hold from various ships captained by Charles Egerton Harcourt-Vernon (1849-1861); ships logs of Midshipman George Ross Divett (1863-1869); those of the H.M.S. Tribune (1818-1822), captained by Admiral Sir Nesbit Josiah Willoughby.

Measurements were taken at set times of the day and the entries were completed by literate, numerate men who had spent much of their working lives at sea. It was an offence to falsify a logbook, but as anyone who has used historical records is aware, the penmanship of the author can vary enormously. To mitigate the chances of transcription errors in the oldWeather data, each entry is transcribed by three people. This data is then fed into a database, which identifies weather patterns and allows scientists to test future climate predictions against past climate behaviour.

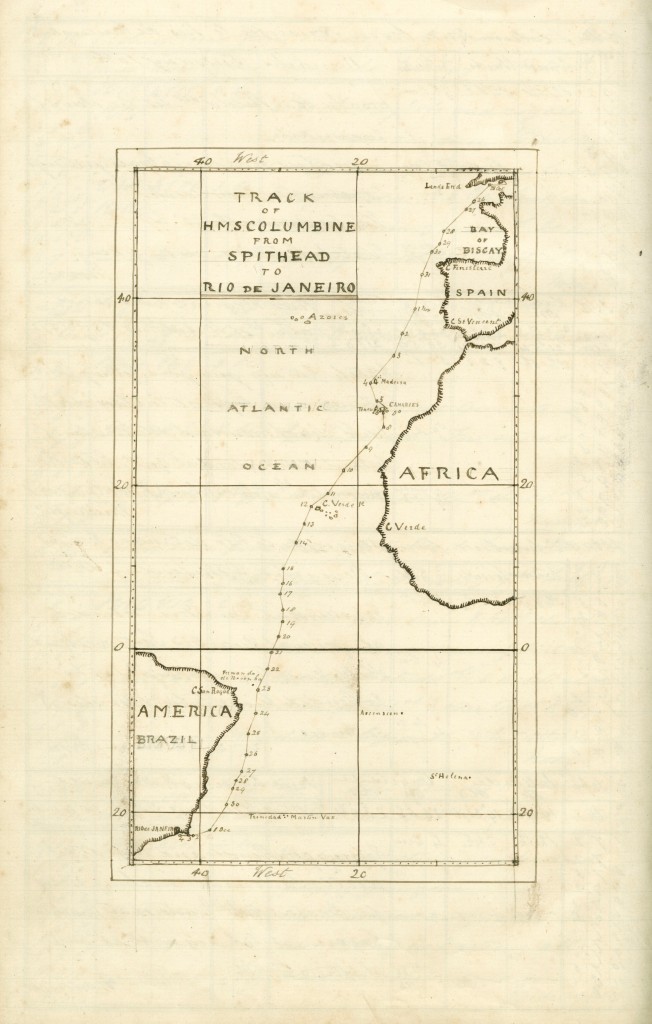

Page showing a map of the route from Spithead to Rio de Janeiro showing the date each point was reached, from the Ship’s Log of H.M.S. Columbine; 1863

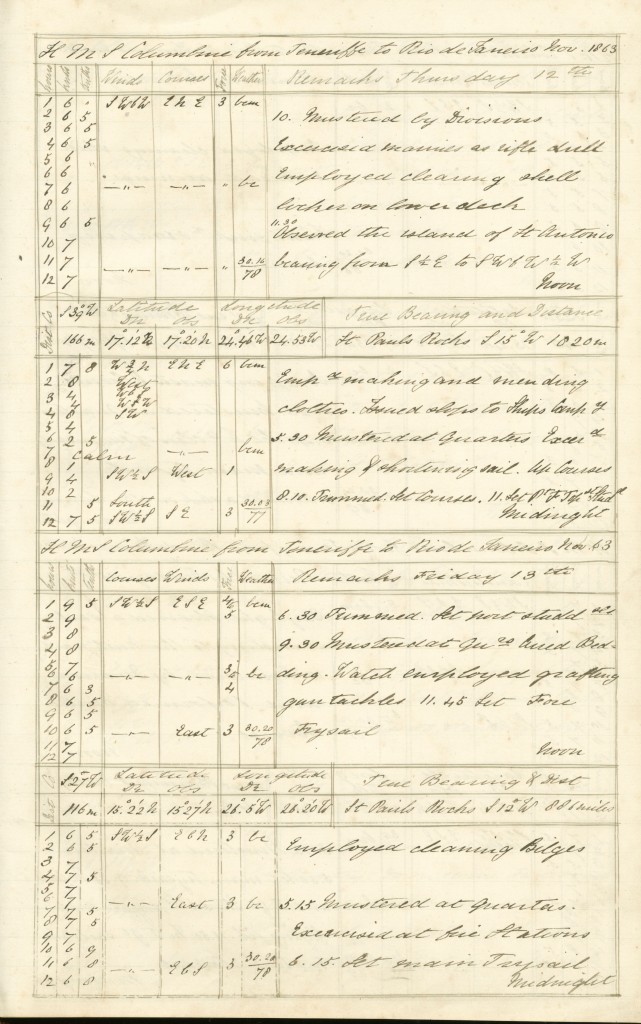

Page from the Ship’s Log of H.M.S. Columbine on her journey from Spithead to Rio de Janeiro, recording details about the wind and weather; 1863

If you’re interested in accessing our records then please see our online catalogue and contact us to make an appointment. If you’ve not seen enough images of floods, then we have a small number of photographs of previous flooding availble in the Historic Collections Online gallery.

This month the School of Sociology and Social Policy’s ‘Making Science Public’ programme is organising a series of free lectures about climate change as part of their project ‘Climate Change as a Complex Social Issue’, examining science communication to the general public and climate change. For more information please see the Making Science Public blog or check the University’s events listings.

Thank you to the Manuscripts team (especially Sarah) for introducing us (Lucy and Georgina) to the water records in person! It’s great to have such rich materials on our doorstep. I hope to be back to look at more next week. In addition to the materials identified above there are also some items in Special Collections that will be helpful in our task to build up a multi-regional climate history for the UK – I’m really interested in the meteorological records of Edward Lowe of Highfield House (now home to the Centre for Advanced Studies)….

Thanks Lucy, it looks like a really interesting project. Let us know if there’s anything more we can do to help.

Sarah, Manuscripts and Special Collections

Hi, thanks for the information you shared. I am working on historical rainfall data and I would like to find some historical stories about rainfall collection in Malaysia. I am not Malaysian, so i have no access to some valuable information in this country, if there is any. I thought maybe there is some information with Uk’s related departments as Malaysia was one of the UK’s colony.

Regards,

Morteza

Hi Morteza, thanks for your comment.

I’m afraid we don’t have anything relating to rainfall in UK colonies. Have you contacted the Malaysian Meteorological Department? They started recording data in 1820 and they might be aware of the location of previous records: http://www.met.gov.my/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=100&Itemid=177

All I can suggest for UK records is that you try The National Archives or perhaps the Royal Geographical Society. TNA’s search page is at http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/SearchUI and they have guidance for people searching for records relating to the Empire and Colonies at http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/research-guides/british-colonies-and-dominions.htm and http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/research-guides/imperial-commonwealth-history.htm. The RGS has more information about their archives at http://www.rgs.org/OurWork/Collections/Collections.htm

Hope this is useful, and I’m sorry we can’t be more helpful.