May 18, 2023, by Sarah Colborne

Reading the correspondence of the Duchess of Portland

This is a guest blog by Arts Faculty Placement student Nabiha Iqbal, who in 2023, worked on cataloguing the papers of Dorothy Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1750-1794).

I was granted the unique opportunity to revisit the lives of the noble men and women of 18th century England through their primary means of communication: letters. Each letter showcased the identity and individuality of the person writing them, whether that be through their handwriting or the contents of the letter itself. I found it fascinating to see such unique perspectives from those that lived hundreds of years ago with their passions, fears, trials and tribulations magnified through a 21st century lens. Uniquely, these were documents curated by England’s finest- barons, viscounts, dukes and duchesses. Yet, despite the fact that they weren’t ‘common’, they did have common problems, the least of which was the breakdown of friendships.

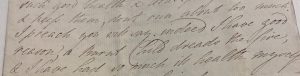

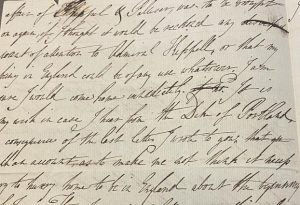

Exhibit A: Letter from the Viscountess Torrington Lucy Boyle asking the Duchess for forgiveness, early 1770s. Pw G 73

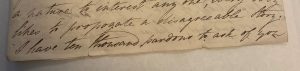

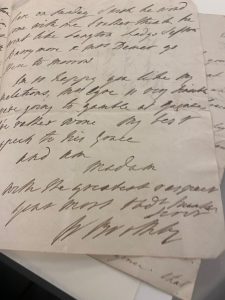

Exhibit B: Letter from Viscountess Torrington Lucy Boyle using 18th century colloquialisms, 1760s-1780s. Pw G 76

I want to highlight Exhibit A here, one of the first letters I read in which the relationship between the writer, the Viscountess Torrington and the Duchess of Portland had soured considerably, causing the Viscountess to earnestly beg ‘a thousand pardons’ from her former friend. She doesn’t shy away from further colloquialisms which is the case for Exhibit B where she proclaims, ‘a burnt child dreads the fire.’ Surprisingly, the English language has not changed much in the last 250 years or so (it would be a different story if this was the 17th century but fortunately, Shakespearean English had more or less faded by the time these letters were authored.) Nevertheless, the age and the handwriting in some of the letters posed considerable difficulty.

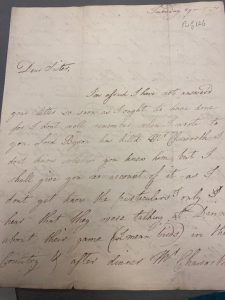

Exhibit D: Letter from William Cavendish which shows writing faded with time. (Here he talks about Lord Byron [great-uncle of the poet] killing someone at a party), c.1765. Pw G 76

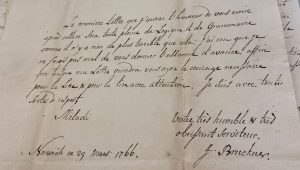

This is also the reason I chose Exhibit E as the letter with the best handwriting, as although it is written in a different language, every word is precisely written and therefore clear. Unfortunately, in some cases like Exhibit F, it was impossible to read certain parts of the letter due to age, which, in instances like this, caused the pages to tear. It is therefore very important to handle each page with the utmost care, something I learned on my first day with the department.

Exhibit E: Letter in French from Reverend Bruckner to the Duchess of Portland, 29 March 1766. Pw G 82

The language used by these individuals also gives us a gateway to delve beyond the fabrics of the letter. With the Georgian era being constantly brought to the spotlight through modern day entertainment like ‘Bridgerton’ and ‘The Duchess’, it is difficult not to be entranced by the inspiration behind these soon to be classics. Many of these letters are evidence of the fact that the Georgian era did indeed herald a new age of free thinking and progress. Politically, the mention of the ‘Whigs’ caught my eye, their influence still somewhat prevalent in modern day society. Further reading and context clues led to the discovery of how well connected these individuals were to their arts, through both ownership and pastimes like the opera, and to each other, through familial ties. The subject in question, the Duchess of Portland, was married to the Prime Minister and is directly related to Queen Elizabeth II. From the category of letters I interpreted, Exhibit G proved to be the most interesting first-hand account of some of the events that transpired in the 18th century. Lord Richard Cavendish, the brother of the Duchess, describes being in the midst of a well-documented conflict between Sir Hugh Palliser and Admiral Augustus Keppel, pertaining to the Battle against the French in 1778. This caused them both to be at the mercy of court martials.

Exhibit G: Letter from Richard Cavendish. He discusses the possibility of returning home from Naples where he was recovering from illness, but unfortunately the sickness returned and he never came back, c.1781. Pw G 105

Ultimately, although I struggled in some parts of my placement, (scouring the internet for ‘Pearo’ and taking far too long to realise it was a dog was not my finest moment) dissecting the inner working of the upper class in Georgian England is a challenge I’m glad I faced.

Conclusions

FAVOURITE WRITER: William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire

BEST HANDWRITING: Reverend. J. Bruckner

WORST HANDWRITING: Sir William Boothby, 7th Baronet

MOST INTERESTING: Lord Richard Cavendish

Further information

The catalogue for the Papers of Dorothy Bentinck, Duchess of Portland (1750-1794) can by accessed via the Manuscripts Online Catalogue (Document Reference Pw G). Further information can be found in Manuscripts and Special Collection’s guide to the Portland (Welbeck) Collection The papers can be accessed in the Manuscripts and Special Collections reading room at King’s Meadow Campus.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply