October 17, 2022, by Kathryn Steenson

Holinshed’s Chronicles: Shakespeare’s textbook

In the 1540s, bookseller and printer called Reyner Wolfe had a grand ambition to write a ‘universal cosmography of the world’, an enormous work that would cover the history of every nation complete with up-to-date illustrations and maps, and, to make it more accessible, written in English.

It was quickly apparent that this was well beyond the scope of one person. Reyner hired assistants and downscaled it to ‘just’ the history of England, Scotland and Ireland, from their first inhabitants up until what was then the present day. Wolfe died in 1573 with his dream still unrealised, and his assistant Holinshed took over lead editorial duties. And it is he who got his name attached to the end result: Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande.

This edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, WLC/P/5, is from 1577. It proved extremely popular and was revised and expanded for later editions. Renaissance authors such as Edmund Spenser, William Shakespeare, and Christopher Marlowe all used it for their works. Shakespeare used a later version, from 1587, as the source for several of his plays. We know this because there are similarities between some of Shakespeare’s text and Holinshed’s text that only appears in later editions. I think this is a polite way of gently accusing Shakespeare of copying.

Despite the intention being to provide a true and complete history, many inaccuracies crept into the Chronicle’s text. On page 239 of ‘The Historie of Scotlande’ in the account of Duncan’s reign, when comparing the characters of Duncan and Makbeth, Holinshed does them a disservice in portraying Duncan as an elderly, naïve king and MacBeth as a cruel but considerably more effective ruler.

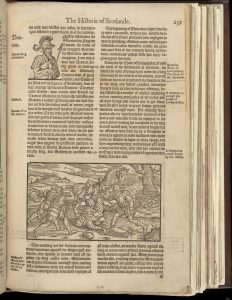

The other thing that isn’t accurate are all the woodcuts, but these weren’t intended to be. They were basically there to bring the text to life and provide a bit of visual interest. Most of them were specially commissioned for the Chronicles, but a lot of them were reused within the text to illustrate different events. This one of Macbeth and Banquo meeting the weird sisters is not reused anywhere else. These two figures on the right are the men, and the three ladies on the right are the weird sisters – described as ‘straunge & ferly’ here (ferly meaning ‘unexpected’, ‘frightful’ or ‘wondrous’ – the word was changed to ‘wild’ in the 1587 edition). This is despite them wearing courtly Renaissance-era clothing, when the real Kings Duncan and Macbeth were unequivocally in the mid-11th century!

The bespoke woodcuts helped make this an incredibly pricey volume. We’re still in the early days of printing so resembles text in medieval manuscripts. This is part of the Wollaton Library Collection, which was once kept at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham. Those of you from Nottingham may know it for its museum, deer park, and music festival Splendour; those of you outside of Nottingham may have seen it in The Dark Knight Rises playing Batman’s home Wayne Manor.

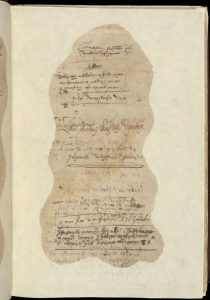

Our copy was very well read. It suffered enough wear and tear that we needed to conserve it. There are pages with bits of text missing and these pages have been repaired, but a basic conservation principle is not to recreate that which is missing, even though with a printed book we’re fairly confident we know what the text would be. There are also lots and lots of annotations, usually of the owner’s names, in the front and back. This page lists Anthony Wagstaffe, and underneath that John Wagstaffe. John was rector of Wolloughton and Cossall in the 1630s, and possibly decided to catch up on his history when he was briefly suspended from entering his own church. His offence was to have let a parishioner visit a folk healer, something that was dangerously close to endorsing witchcraft in the Church’s eyes.

This book was originally bought by Sir Francis Willoughby and there are a fair few marginal notes on the text written in his handwriting. Sir Francis was clearly a person who liked to scribble in books when he wasn’t fighting with his wife Elizabeth. His turbulent first marriage produced no sons who survived infancy, which meant his son-in-law would inherit, but the two had a falling out. After Elizabeth’s death Francis quickly remarried to try for a son. The second Mrs Willoughby soon fell pregnant but poor Francis didn’t live to see the baby born. He died suddenly in 1596 and was very hastily buried that same night, amid rumours that his new wife had poisoned him. Six months later his newborn baby – another daughter – followed him to the grave. Theirs was a family history fit for a Shakespearian tragedy.

This book, along with many others from the Wollaton Library Collection, is available to view in the Reading Room at King’s Meadow Campus.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply