March 9, 2022, by Kathryn Steenson

International Women’s Day: Dorothy Brett

This is a post by ‘Editing DH Lawrence# co-curator, Dr Rebecca Moore.

Dorothy Eugénie Brett, born in London in 1883, was an artist of noble birth. Having had drawing lessons since the age of five, she joined the Slade School of Art in 1910, and studied there until 1916 where she became known simply as “Brett”. She met DH Lawrence in 1915, but it was not until 1923 on one of Lawrence’s return trips to England from Taos, New Mexico that they developed a closer relationship. One evening, at the artist Mark Gertler’s home, Lawrence expressed a desire to set up a kind of utopian artist commune that would be called Rananim. Nothing came of this, but it was in this spirit that Brett followed Lawrence and Frieda back to New Mexico in 1924. Brett would never live in Britain again and remained in New Mexico for the rest of her life.

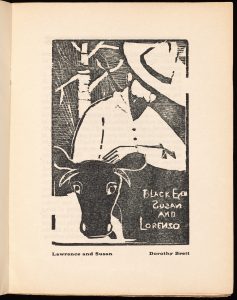

Brett painted extensively in Taos, New Mexico, occasionally collaborating with Lawrence on the same canvas. She also typed up various manuscripts for Lawrence, including the short story ‘The Woman Who Rode Away’ (1925) which was set in New Mexico. Manuscripts and Special Collections have a selection of photographs taken by Brett at Lawrence’s Kiowa Ranch in Taos – including one of Lawrence milking his cow, Susan. Brett was primarily a painter, but she produced a woodcut portrait of Lawrence and Susan for the journal Laughing Horse to accompany Lawrence’s piece on the cow in question. As a painter, Brett is known for her vivid use of colour, and her occasionally dreamlike compositions, some works, like Massacre in the Canyon of Death: Vision of the Sun God (1958) are Surrealist in style.

After Lawrence’s death in 1930, Brett wrote a memoir of their time together: Lawrence and Brett: A Friendship. Brett’s preface is modest:

‘I am a painter, not a writer; I have done my best in my power for the man that every woman and most men loved. His death is our tragedy, not his. That unconquerable spirit flamed daringly … flamed up and went out … For me he still lives; the world is still lit by his flame. […] There is no other way except by the magic of words to make him stand forth and live again. Alas that I have not the magic of his pen.’

But it is precisely because she is a painter and an artist that her memoir is so striking, and so different to other recollections of Lawrence. Written almost entirely in the present tense, and to Lawrence, Brett’s memoir has an immediacy which makes it full of life. She is impressionistic too in her descriptions:

‘The rich emerald alfalfa, dark and heavy, is spreading abundantly. I sit in the warm sunshine outside the big studio, writing letters. You come strolling out of your house, across to me.’

Brett has achieved, as she wished, to use the magic of words to capture a life and it is astonishing how vividly her memoir paints a picture of her life in New Mexico with the Lawrences. Brett is not overshadowed by Lawrence’s ‘unconquerable spirit’ – her art, photography, and writing have preserved her own extraordinary talents.

The Editing DH Lawrence exhibition runs until the 29th May at Lakeside Arts and is free of charge. It marks the end of the Unlocking DH Lawrence Project to catalogue and digitise our archives relating to the life and work of the author. More information about our exhibitions is available from our website, Twitter @mssLakeside, and newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply