February 22, 2022, by Kathryn Steenson

Finding leaves in books

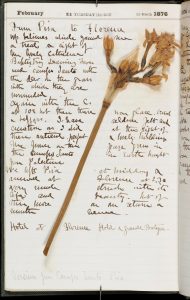

On this date, a man picked a daffodil whilst on holiday, carefully pressed it, and kept it between the pages of his diary. Being early spring, it was only small and the flower buds were still closed. The stem is a greenish-brown. The petals are yellow. The flower is 146 years old.

People kept pressed flowers for the same reasons we do today, which in this case was a memento from a trip to Italy. Dr Edward Wrench was a surgeon from Derbyshire who was a committed diarist for 56 years. On the entry for 22 February 1876 when he picked this ‘Narcissus from the cemetery Campo Santo’ (Camposanto Monumentale di Pisa), he had been moved to do so by the peace and beauty of the cathedral in the early morning, writing in his signature awful handwriting:

“From Pisa to Florence: Up betimes which gained me a treat a sight of the lovely Cathedral Baptistry Leaning Tower and Campo Santo with the dew on the grass with which they are surrounded…..I have seldom felt such emotion as I did at the sight of these antient perfect & lovely buildings. The flower on this page grew in the Campo Santo in earth brought from Palestine….”

His diaries are a treasure trove of information about Victorian society, and flowers were not the only things tucked inside his diaries: there are photos, newspaper cuttings, maps and programmes, each one recording a special or notable event for him.

But some leaves were kept for reasons that are not as apparent to us several centuries later.

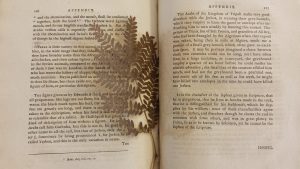

This leaf was one of several placed in the pages of a semi-relevant book: ‘Select specimens of natural history, collected in travels to discover the source of the Nile, in Egypt, Arabia, Abyssimia [sic], and Nubia’ (volume 5 of Travels to discover the source of the Nile by James Bruce, Travel Collection Oversize DT53 .B7). My botany isn’t good enough to identify what it is, but I would be very surprised if this plant had come from anywhere other than Britain. Travel books like these were generally purchased by armchair travellers (and sometimes written by them too, although James Bruce was a genuine explorer and adventurer). Our version of this book was printed in 1790 but there’s no way to tell how long the leaves have been in there. There is a faint shadow left on the page where the colour and moisture has transferred on to the paper, and from this we can deduce that they had been undisturbed for a considerable period.

The previous owners of the book include W Porden (the architect, whose daughter married explorer Sir John Franklin) and Philip Lyttelton Gell (editor of the Oxford University Press and grandson of the explorer Sir John Franklin). Not only did Franklin never go anywhere near the Nile, he spent most of his naval career in the Arctic wastelands. Any romantic notions of this plant being plucked by Franklin’s own hand in a far-off country and carefully preserved within this book are, alas, mostly likely just notions.

Since discovering the leaves tucked inside, we have put them within acid free paper, but left them in their place.

And then there are more poignant reasons why people have such keepsakes.

This crossed letter edged in black is from the aunt of Margaret Mellish, undated but written in the 1850s, several years after the loss of Margaret and her husband William’s baby son (possibly also called William) to a short illness. In it, she reports that she went to visit the ‘grave of your little angel boy’ when she was in ‘the Island’ (Prince Edward Island in Canada) and describes it as a pretty, peaceful spot. The lettering had faded and wild roses had grown around it, and she had enclosed some of them within the envelope, labelled ‘From Baby’s Grave Prince Edward’s Island’ and originally sealed with black wax. It contains some incredibly fragile dried rose leaves, but two of them had fallen out of the envelope. These are the ones shown in the photo – a small, delicate token of remembrance sent to parents living an ocean away from their child’s resting place, in the hopes it might help them feel closer to their infant son.

The items mentioned here are available to view in the Manuscripts and Special Collections Reading Room on KMC. Please email us to make an appointment in advance, telling us when you would like to visit and the reference numbers of what you would like to see. For more information about the collections, please see our website, newsletter Discover, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply