May 5, 2021, by Kathryn Steenson

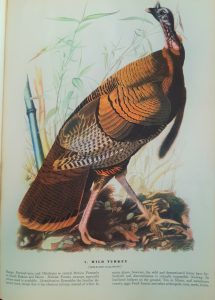

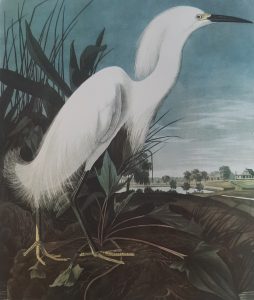

Birds of America: Flights of Fancy

There are only 120 copies of Audubon’s ‘Birds of America’ known to survive, the vast majority in university or other public libraries. Different editions occupy multiple places in top 10 lists of the most expensive books ever sold. The 4th Duke of Portland, whose archive we hold, owned a complete copy of the first edition, which came up for sale at Christie’s in 2012.

It’s just a pity we didn’t have £6million lying around, otherwise we’d have bought it.

We do have copies, but ours are from the 1930s, a good hundred years after the first edition, and still valuable in their own right. But what makes a book of birds so highly sought after that it sits alongside medieval illuminated manuscripts and unique religious manuscripts?

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin in 1785, d. 1851) was a painter and ornithologist who decided to combine his interests, and paint every species of bird in North America. His magnum opus took fourteen years, interrupted as it was by the difficulties in travelling and Audubon’s own precarious finances – he was once briefly imprisoned for debt, and although he earned money from teaching drawing and selling sketches, his wife supported her husband and children through her job teaching at a local school.

Audubon sailed to England in 1826 with many of his watercolours, intending to make a little money from exhibiting his art and gain enough interested subscribers to pay for the book to be printed. He was wildly successful. There was something exotic about the North American wilderness in both the pictures and in Audubon’s story that caught the imagination of the British aristocracy, ably assisted by Audubon’s willingness to play up his ‘Woodsman of America’ moniker to earn money giving public lectures. It was probably during this tour that the Duke of Portland put his name down as a subscriber.

The finished work was enormous in scope and in size: 435 hand coloured plates (50 people were employed, assembly-line fashion) on pages 3 feet tall, which allowed some of the birds to be depicted at life-size. It was considered one of the most beautiful and scientifically important ornithological works ever completed.

Well, mostly. It was claimed that Birds of America identified 25 news species, including the ‘Bird of Washington’, which was one of the images Audubon used in his publicity tour. Nobody else ever reported seeing this species, much less obtaining an actual specimen. It could have been an honest mistake, but Audubon had previously invented species to ‘prank’ his rivals, and modern the consensus is that the Bird of Washington was a fraud rather than error.

In the introduction to our 1930s volume, Audubon is hailed as a good example of conservation. He recognised the need to preserve the birds’ habitat, and whilst it may not have been the first recorded instance of some species, it was certainly the last record of at least half a dozen. Within 11 years of Audubon’s trip to Labrador in Canada, the Great Auk was extinct and the Passenger Pigeon was hunted to extinction by 1914.

Unfortunately, Audubon’s method for drawing the birds was the conservation-unfriendly method of shooting them. Other ornithologists would taxidermy the birds, but Audubon preferred to string them up on wires to achieve the more natural poses he wanted. He worked long hours for several days in a row to prepare, draw and then paint a single bird.

The method got results, with our book acknowledging that Audubon’s “scientific abilities are less striking that his skill with the brush”. The lifeless drawings and glassy-eyed specimens in earlier natural science texts were replaced with creatures in the landscapes of their natural habitat: standing on rocks as the waves crashed against them, perched in trees feasting on insects, or swooping through the air. For people in the 1830s, it must have been very exciting to see these large, full colour illustrations of alien landscapes and wildlife. It’s a pity that Audubon didn’t credit the man who painted some of them, Joseph Mason. Mason was Audubon’s pupil and was exceptionally talented at flowers. Fifty of his paintings were used in Birds of America, accurately representing the habitat as well as establishing scale and proportion to the birds, something that was new and helped establish the books scientific credentials. Mason wasn’t credited for his art, much to his annoyance, and nor did Audubon acknowledge Mason’s practical help in their expeditions to acquire the birds.

None of this is to say that ‘Birds of America’ wasn’t significant for ornithology or art history, or that Audubon wasn’t a talented and devoted artist. The accusations of plagiarism and fabrication didn’t harm the book at the time and don’t seem to be hurting it now. If you’d like to see what all the fuss is about, you can book an appointment in the Reading Room to look at our copy. More information about booking and what to expect on your visit is here. For more information about the collections we hold, see the website, follow us on Twitter @mssUNiNott, or subscribe to the magazine Discover.

All images taken from Audubon’s ‘Birds of America, with an introduction and descriptive text by William Vogt’, (1937). Ref: Porter Collection Oversize QL681 AUD

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply