June 8, 2020, by Kathryn Steenson

Colley Cibber

If ever there was a case of success and fame being the result of luck, rather than talent, then Colley Cibber is it. He was an awful poet who became Poet Laureate through his political connections; a middling actor who connived to became a pioneering actor-manager in Drury Lane; and an unscrupulous and divisive man whose autobiography captured a pivotal moment in theatre history.

Image of Colley Cibber from his autobiography, An apology for the life of Mr. Colley Cibber, comedian and patentee of the Theatre Royal (1822). Ref: Cambridge Drama Collection PR3347.A8

In 1740, thirty years after he became manager of the Drury Lane theatre, Cibber published his autobiography. ‘Apology’ here means something akin to a defence, and there is certainly little by way of remorse in this hugely successful, wildly entertaining, and moderately accurate account of his professional life (his personal life, including his falling out with many of his surviving children, is hardly mentioned). In the 1790s Cibber had success as a comedic actor (possibly because his natural brash, showy personality suited those parts) and gradually worked his way into a position of being able to take over the theatre company. He was opportunistic and manipulative in business, and his theatre was successful, despite his insistence on writing and acting in some of the productions. The ‘Apology’s importance is less due to Cibber’s achievements, but more the time he lived through: the rise of the actor-managers, the change in cultural tastes, and the gossipy stories of the actors and theatrical scandals during a time when there are few contemporary records of London theatre.

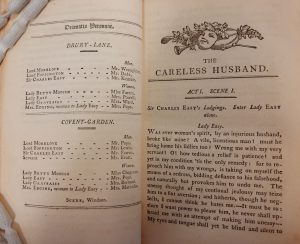

‘The Creless Husband’ from ‘The dramatic works of Colley Cibber, Esq’ (1760). Ref: Cambridge Drama Collection PR3347.A1.D60.

The comedy ‘The Careless Husband’ (1704) is considered Cibber’s best play. It survived in repertory theatre throughout the 18th century and mentions of it cropped up in dramatic criticism until the early 20th century. The husband in question is serially unfaithful, and in the cornerstone moment of the play, his wife finds him and the maid asleep together in a chair. She covers his bare head with her scarf to keep him warm, an act that makes her husband realise how wonderful she is, and the two have a heartfelt reconciliation.

Cibber was good at business and a decent employer, though his actors cannot always have been pleased at his insistence at performing in productions or at staging productions of his own works. He was less popular with playwrights whose work he rejected (sometimes sharply), but generally he made sound choices. He was astute enough to notice the audience demand shift from Restoration comedies to sentimental comedies, which best suited both his writing and acting style, but his tragedy plays were, well, a bit tragic.

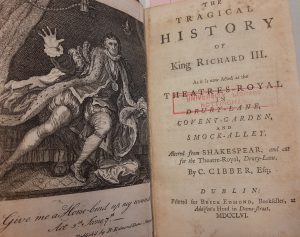

The tragical history of King Richard III: as it is now acted at the Theatres-Royal in Drury-Lane, Covent-Garden and Smock-Alley, altered from Shakespear, by C. Cibber’. Ref: Cambridge Drama Collection PR1269.S42

Cibber’s first attempt at staging Richard III in 1699 was a disaster. In his own words:

“…the Master of the Revels, who then licensed all plays for the Stage…expunged the whole first act, without sparing a line of it…[I applied] to him for the small indulgence of a speech or two, that the other four acts might limp on, with a little less absurdity! No!”

However, the printed version was published in its uncensored entirety. Several years later a theatre company risked staging the full play and suffered no penalty. Others followed, and it became so popular that audiences preferred it to the original Shakespeare play until the late 19th century. Cibber’s version took the basic structure and 800 lines from Shakespeare’s original play of Richard III, then added extra speeches (some he wrote, others taken from different Shakespeare plays), and included more violence, including the on-stage murder of the Princes in the Tower.

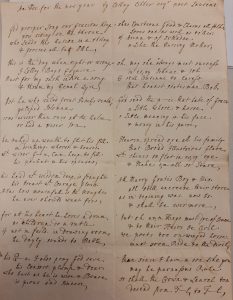

Cibber became Poet Laureate in 1730. Despite there being precedent for appointing playwrights rather than poets, it was still a superficially odd choice. His poetry was considered worse than his plays, and even Cibber himself wrote in his ‘Apology’ that he did not think they were much good. The Poet Laureate is the official government poet, and Cibber’s appointment was assumed to be a reward for his support for the Whigs, of which the then-Prime Minister Robert Walpole was a member. The poem ‘Ode to a New Year’ was probably one of the duty poems he was required to write, none of which were great, but if you want to experience some of his worst work (especially his odes to celebrate the Royal birthdays) then some have been included in D. B. Wyndham-Lewis and Charles Lee’s anthology of bad verse, The Stuffed Owl (1930).

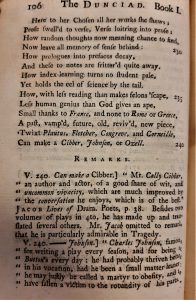

Footnote from The Dunciad by Alexander Pope (1727) about Colley Cibber. Ref: Special Collection PR3625.D8.D33

Cibber’s vainglorious attitude would have earned him enemies even if his talent had been as large as his personality. One of his long-running feuds was with the poet Alexander Pope. Whilst on stage in 1717 Cibber, himself no stranger to terrible reviews, mocked a poorly-received farce Pope had recently written. Pope, sitting in the audience, was enraged (his reaction when his nemesis became Poet Laureate was exactly as you would imagine). To his credit, Cibber largely ignored Pope’s provocations until he finally lost patience in the 1740s and mocked Pope’s sexual prowess – which stung all the more as Pope was unmarried and a childhood illness had stunted his growth and left him with a spinal deformity. In one version of his mock-heroic narrative poem ‘The Dunciad’, in which the Goddess Dulness strived to convert the world to stupidity, Pope cast Cibber as the ‘hero’, King of the Dunces. As it is Pope’s reputation and works that have survived whilst Cibber’s faded into obscurity, this has, in some respects, become his literary epithet.

The books and archives featured here are part of Manuscripts & Special Collections extensive theatre and drama holdings, which include rare books of dramatic criticism, acting, history of theatre and actors, and the archives of several East Midlands theatre companies. Normally these are available to view in the Reading Room, however due to the Coronavirus pandemic we are closed until further notice. Please see our website and Twitter feed for updates. If you’re a member of the University, you can also access the library resources Drama Online, Victorian Popular Culture, and Digital Theatre.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply