January 17, 2019, by Kathryn Steenson

Censorship and Banned Books

An auction house in Derbyshire is selling a rare 19th century edition of ‘Fanny Hill – Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure’ by John Cleland, which was banned not long after its publication in 1748. It’s the story of an orphaned girl who goes to London looking for domestic work and instead ends up working in a brothel. It is euphemistic and flowery rather than explicit in its descriptions, and is famous for being the first work of pornographic prose.

It was far from the only creative work to fall foul of Britain’s long and convoluted censorship laws. Censorship of stage plays (often for blasphemous content) was exercised by the Master of the Revels since Henry VIII’s reign but from 1737 responsibility was transferred to the Lord Chamberlain’s Office and the rules were tightened to protect Robert Walpole’s unpopular government from the wrath of the satirists’ pens.

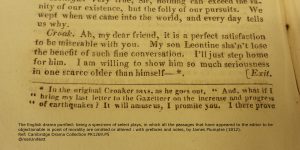

Censorship was as contentious then as now, but there was a market for ‘family’ versions of plays, such as this one from 1812. Clergyman and dramatist James Plumptre selected plays carefully for this three-volume set and outlined at length his reasons for doing so. Most of his changes were on grounds of sex or religion but not always – here he removed reference to earthquakes from Oliver Goldsmith’s ‘The Good Natured Man’ on the grounds that it was too awful and serious a subject for general ridicule on stage. As justification Plumptre lists a number of earthquakes that had struck England and the ‘dreadful’ Lisbon earthquake in 1755 that killed over 10,000 people.

Goldsmith’s play was only a moderate success in theatres, but the print version proved more popular with the public. In the main plot, the uncle of the titular over-generous and good-natured man schemes to have him arrested and imprisoned for debt to teach him a lesson. The romantic sub-plot (the ‘deceit’ requiring ‘modification’) is Leontine’s plot to elope with penniless orphan Olivia, although everything turns out all right when Olivia’s true identity as a wronged heiress is uncovered.

Officially it was the Lord Chamberlain who was the final authority on stage productions. Although he was less inclined to worry about earthquakes, he was also less inclined to explain his reasons. All plays to be staged in public needed a licence. For a fee, his Office would examine a script and would grant or refuse a licence for a script. Until early 20th century this control was absolute: judgement was final, with no explanations or appeals, and no proper guidelines. Scripts were judged according to the social and moral mores of the time and at the Lord Chamberlain’s discretion.

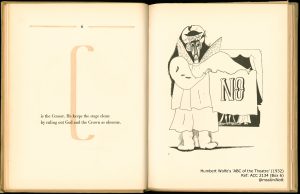

Once a script had a licence, however, it could be performed by anyone at any theatre, and the Lord Chamberlain would only intervene if a complaint was made that a performance had deviated from the script (which included not just spoken parts but stage directions etc). Humbert Wolfe, author and civil servant, expressed the frustrations of working within the system in his ‘ABC of the Theatre’, which is styled as a children’s alphabet primer.

Theatre managers or publishers who defied the censors risked prosecution. In 1963, an uncensored version of Fanny Hill was published and came to the attention of police almost immediately after it went on sale. Copies were seized from a London bookseller who was successfully prosecuted for distributing obscene material. The publisher had been emboldened by the Lady Chatterley trial three years earlier, where Penguin Books had successfully defended itself from accusations of obscenity for publishing D H Lawrence’s novel. Lawrence never got to see the trial – he died of TB in France in 1930 – and had faced numerous difficulties in getting ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ in an unexpurgated form because of its descriptions of an adulterous affair between an upper class woman and her working class lover.

It took several judicial cases and two decades for it to be published unabridged in America and the UK, by which stage Lawrence’s critical reputation had begun to improve and there were witnesses prepared to argue his novel had literary merit. The same arguments could not be made of ‘Fanny Hill’, and neither could the defence persuade the court that the book was merely bawdy rather than pornographic.

It took several judicial cases and two decades for it to be published unabridged in America and the UK, by which stage Lawrence’s critical reputation had begun to improve and there were witnesses prepared to argue his novel had literary merit. The same arguments could not be made of ‘Fanny Hill’, and neither could the defence persuade the court that the book was merely bawdy rather than pornographic.

Fanny Hill remained banned in the UK until 1970.

Our website has more information about our collections, which sadly do not include a copy of ‘Fanny Hill’, but do include numerous censored and uncensored versions of literary and theatrical works. The Cambridge Drama Collection and DH Lawrence Collection may be of particular interest to anyone interested in the history of theatre or Lawrence’s works, including the various versions of ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’ and the trial. You can also read our newsletter Discover and follow us on Twitter.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply