December 12, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

Family Hair-looms

Does anyone care for a short story about death, documents and hair? Back in November, we tweeted this story with the theme of #HairyArchives as part of Explore Your Archives week. It proved quite popular, so we’re re-telling a version of it here for those of you who missed it.

Usually, we take advantage of the HairyArchives hashtag to roll out the usual images of ridiculously cute fluffy animals or splendid facial hair, like this one. Just think of the split ends!

This time, we wanted to tell a story, about a young woman who left a very tangible piece of herself in the archive. Meet Lady Charlotte Boyle (b.1731). This is her portrait in Chiswick House, now run by English Heritage.

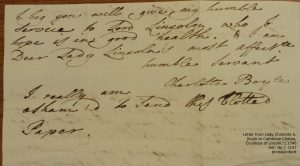

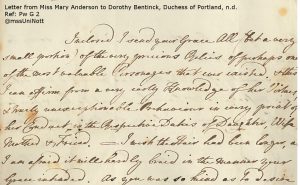

She was the only surviving child, and thus very wealthy heiress, of the 3rd Earl of Burlington, and she was described as ‘one of the valuable Personages that ever existed’. This is a letter from her in her own handwriting to Lady Catherine, Countess of Lincoln, talking about family and the weather, and apologising for her blotted letter.

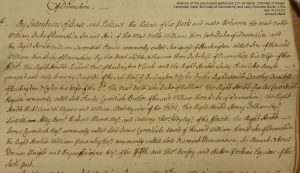

Like all great love stories, this one began when two wealthy families looked at their social and financial position, sought a mutually advantageous match, and got their lawyers to draw up a pre-nuptial agreement. Charlotte would marry William Cavendish (later 4th Duke of Devonshire and, even later, Prime Minister).

They married in 1748, much to the dismay of William’s mother. Her opposition had nothing to do with Charlotte personally: she had desperately wanted her son to marry for love, and not into a family surrounded by as many salacious rumours as the Boyles. Rumours such as Charlotte’s father and the architect William Kent being rather more than just close friends. There’s even poetry about it:

Charlotte’s sweet-tempered older sister Dorothy married their mother’s former lover, the notoriously cruel Earl of Euston, whose brutality may have facilitated Dorothy’s death in childbirth aged only 17. The baby did not survive either. The Earl was unrepentant and a year later was disowned by his own father for hounding a tenant on his estate to suicide.

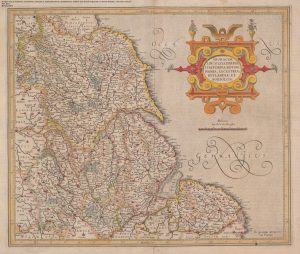

William Cavendish’s parents, unusually for the time, had married for love. His mother had come from a middle-class family who lacked both the social graces of the aristocracy, and their dynastic sensibilities. When it became clear that they couldn’t stop their adult son choosing a wife out of duty (i.e. wealth), William’s formidable, idealistic mother cut herself off from her family and refused to reconcile. Despite what became an increasingly embarrassing scandal, the young couple got on with married life. Shortly after her 6th wedding anniversary, Lady Charlotte gave birth to George, a younger brother for William, Dorothy and Richard. Later that year, she visited her mother at Uppingham in Rutland.

She played a game of shuttlecock despite feeling unwell. She had a headache, which became a fever and vomiting. Then the unmistakeable pustules appeared, first on the face and spreading rapidly down the body. Charlotte had smallpox.

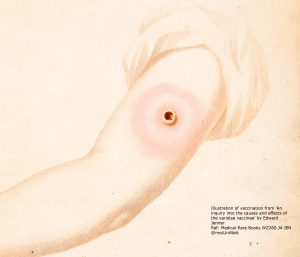

Let’s briefly interrupt Charlotte’s suffering to mention Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. She tried to introduce smallpox inoculation to England in the 1720s, having seen it practised when living in the Ottoman Empire.

Smallpox was an issue close to Lady Mary’s heart. It had killed her younger brother and marred her famous beauty, but she wanted to stop others suffering as she had. Inoculation worked: a century before Edward Jenner’s famous cowpox vaccine, there was a way to protect people from smallpox. Unfortunately people were suspicious of foreign folk-medicine and – with some justification – afraid it could cause a full-blown case of smallpox in a patient who would otherwise have been healthy.

Within a week of falling ill, Lady Charlotte was dead. Her funeral took place on Christmas Eve 1754. She was just 23 years old, a mother to four children aged under six, and pregnant with her fifth.

This is her hair.

The letter is every bit the 18th century stereotype: faded brown ink, red sealing wax, paper that curls itself into comfy creases unless held open. The hair is light brown and despite being a little dry – the oil has leached into the paper – could have been cut last week. The lock of hair was sent to her daughter Dorothy years later, a ‘precious relic’ of the mother she barely remembered. It’s a tiny physical connection reminding us that the names we read in faded ink were real people who were loved and whose memories were treasured after they were gone.

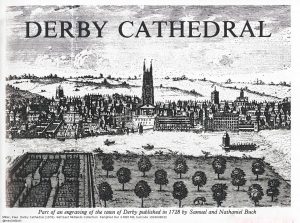

William inherited all the lands and property that he claimed he’d married her for, but it was no consolation to him. Despite his mother’s fears, he loved Charlotte deeply, and their marriage had been a happy one. He never remarried and after his death in 1764, he was interred in Derby Cathedral where Charlotte was buried 10 years earlier. After his funeral a woman’s comb, silk bag and handkerchief were found in his desk drawer. They were the possessions Charlotte had had on her the day she died.

He kept her things beside him in life. And now, she lies beside him in death.

The images here are all taken from the archives and rare books held at Manuscripts & Special Collections, and if you would like to look at them in the Reading Room then please contact us to make an appointment. Finding locks of hair in archive collections isn’t particularly unusual, and hair that wasn’t kept in envelopes was often twisted and braided into lockets or broaches. You can learn more about our collections by following us @mssUniNott or from our newsletter Discover.

The archive of the Dukes of Devonshire is at their family seat, Chatsworth House in Derbyshire.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

![Illustration of a long haired, bearded faquir [faqir] holding his arms above his head as posing for a penance. The caption reads, "The Figure of a Penitent as they are represented in little under the Banians great Tree".<br /> From: Collections of travels through Turky into Persia, and the East-Indies : being the travels of Monsieur Tavernier Bernier, and other great men. London : Printed for Moses Pitt at the Angel in St. Pauls Church-yard, 1684. Section: "The six travels of John Baptista Tavernier, Baron of Aubonne, through Turky and Persia to the Indies", plate facing p.167.](https://blogs.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscripts/files/2018/12/17-32003p-191x300.jpg)

Leave a Reply