January 22, 2018, by Kathryn Steenson

The Curious Case of Benjamin Cockayne

By October 1719, Churchwardens Stephen Turpin and John Pimm had had enough of Benjamin Cockayne, the bad boy of Bramcote. For seven years, they had watched with increasing concern his immoral lifestyle, his drunkenness, and his routine abuse of his neighbours. They brought a case against Cockayne to the ecclesiastical authorities and there was no shortage of people willing to bear witness to his blasphemous and licentious behaviour.

He was also the vicar of Attenborough and curate of Bramcote.

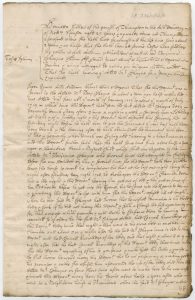

Cause papers, Office v. Cokayne: the said Benjamin Cockayne had been frequently overseen in strong drink or was a common drunkard or prophane curser and swearer or an obscene and filthy talker in common conversation…

Cockayne was born in Derbyshire in 1684 and was appointed vicar of Attenborough with Bramcote in 1712. The investigation was very thorough: numerous presentment bills, memoranda, depositions from 30 witnesses, and Cockayne’s answers attempting to defend himself.

Cockayne seems to have had a fondness for the odd glass of ale. He once got stuck upside down in a hedge and had to be extricated by a passer-by. He was observed striding around Bramcote churchyard swearing and cursing. In the local ale houses he had used such ’abominable and scandalous expressions’ that fellow drinkers – his parishioners – had reprimanded him. His response was that he didn’t care and God Almighty had turned him out because he had sold his soul to the devil.

Possibly due to his hangovers, or possibly because he didn’t care, Cockayne was regularly absent from his own church services. His response to those allegations was to claim a conspiracy, orchestrated by his father-in-law in an attempt to break his marriage and supported by the illiterate dissenters of the parish. Non-Conformism wasn’t a crime thanks to the Toleration Act of 1649, but it still challenged the Church of England’s superiority and dissenters were therefore considered morally suspect by the church authorities.

However, if the clergyman is turning up at church the worse for wear, or declaring he has sold his soul to the Devil, then of course some of the congregation are going to find a different church.

Cause papers, Office v. Cokayne (faults of clergy, not performing duties; faults of clergy, not leading a moral life)

Terrible as this behaviour was, there is an element of farce about it, but unfortunately Cokayne had a darker side to his character. One of the charges brought before the ecclesiastical court related to shortly before his marriage, in which he was accused of begetting a bastard child on his 23-year old maid, Henrietta Gilbert.

Her story begins with her describing leaving the house on several occasions to avoid his attempts to seduce her. Late in the night of the 26th December 1718, Cockayne went to Henny’s room and, being rebuffed again, cried out that he wished damnation to his blood, body and soul if he did not marry her, and that he would fetch a marriage licence at the first opportunity.

These were the magic words. As a poor servant girl, her life options were extremely limited. Being the wife of a vicar, even a reprobate like Cockayne, she would have a socially respectable position and a materially comfortable life. Cockayne might not have been the ideal husband but as a live-in servant, she already had to put up with his behaviour. And he was still a man of the cloth. Perhaps she believed his promise meant something.

Benjamin Cockayne did not fetch a marriage licence at the first opportunity. Nor did he fetch one at a later opportunity when she asked about the wedding arrangements, and neither did he fetch one at his last opportunity, when Henny informed him she was pregnant.

Instead, poor Henny was ordered to leave her job and her home, her reputation in tatters. In court, Cokayne denied fathering the child, and insisted Henny had been entertaining men in his house when he was away visiting his future wife’s family. In effect he had named his father-in-law as both an accuser and an alibi. The court documents do not state the cause of the family feud that led Cockayne to believe his father-in-law wanted to break up his marriage, but an illegitimate baby would be a very good reason.

If it began as a domestic dispute, the whole community very quickly chose a side, and were almost universally united against their vicar. The court heard from Hanna Morgan and her labourer husband Richard, whose child had died some six years earlier. Morgan reported that the death had taken place on a Sunday morning around the time of the corn harvest, and that he visited the vicar in the evening to ask him to bury the body the following day. Cockayne did not, and despite repeated requests from both the grieving father and the parish clerk, the child wasn’t buried until the following Friday afternoon, by which time ‘the dead corps smelt so strong that people were scarce able to stay in the house’.

In his defence, he supplied the parish register showing the burial took place in July 1714, which would be early for corn harvest. Registers did not routinely include dates of death, but Cockayne was implying the Morgans’ grasp of time was faulty and that he mis-remembered the two or three days it took to hold the funeral as a week.

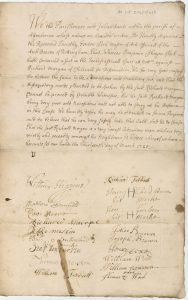

The vicar’s excuses didn’t convince the court and on 8 November 1720 he was temporarily suspended from his ecclesiastical duties. Astoundingly, he remained in position and apparently unrepentant until his death 28 years later, having spent that time periodically bringing his former accusers before the church courts for a variety of grievances. A suit he launched against Richard Morgan was so harsh that 18 parishioners petitioned the Archdeacon protesting the vexatious and malicious action against a man who was too poor to defend himself.

Cockayne’s 35-year tenure as vicar was commemorated with a simple memorial stone in Bramcote church. For anyone interested in a fuller account, the documents relating to Benjamin Cockayne in the Archdeaconry Collection are available to consult in the Reading Room.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply