September 1, 2015, by Kathryn Steenson

Watching Lady Chatterley

It’s either surprisingly chaste or shockingly racy, but fifty-five years after being the subject of an obscenity court case, the sexual content of Lady Chatterley’s Lover is once again making the news.

The BBC has commissioned a one-off 90 minute version of DH Lawrence’s 1928 novel, which will air on 6th September. The sexual relationship it may or may not show in graphic detail is between Lady Connie Chatterley and Oliver Mellors, the gamekeeper on her husband’s estate. The novel is set shortly after WWI, from which Connie’s husband Clifford Chatterley returned home paralysed. Frustrated and isolated as the couple become increasingly physically and emotionally distant, she and Mellors begin an affair.

Both the description and the concept of this affair caused outrage. Lawrence described the details of the characters’ physical relationship as well as their emotional one, and he did so using language still considered strong profanity. The portrayal of adultery was of general moral concern, and this was compounded by the taboo of relationships between upper-class woman and working-class men.

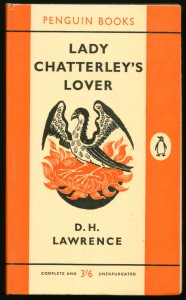

The first edition was printed privately in Italy in 1928. A decade or so earlier, another of Lawrence’s books, The Rainbow, had been banned after an obscenity trial, which probably did little to encourage publishers to take a risk. A censored version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was first printed in the UK in 1932, but it was not until 1960 that a British publisher attempted an unexpurgated edition.

The trial of Penguin Books under the Obscene Publications Act was headline news, although Lawrence did not live long enough to see it, having died of TB in 1930 at the age of 44. As well as novels, he wrote poetry, short stories, plays, essays, and criticism, but despite this enormous body of work produced, his place in popular culture is defined by the six-day trial. The defence case rested upon establishing the book’s literary merit and determining whether or not it would deprave and corrupt readers. Thirty-five defence witnesses were called, including authors, clergymen and academics. The prosecution got off to a bad start by asking the jurors to consider whether this was a book they would wish their wife or servants to read. Quite apart from the paternalistic class attitude, it would be interesting to know what the three women jurors thought of the suggestion that they were competent to sit on a jury but not to choose their own reading material.

It took the jury only three hours to unanimously declare Penguin Books Not Guilty. Thousands of copies were delivered to bookshops in anticipation of public demand. They sold out within days.

Cutting from the ‘Nottingham Evening News’ concerning the ‘Not Guilty’ verdict in the Lady Chatterley’s Lover trial, 3 Nov. 1960 (Ref: La Z 13/1/1960/11/3/153)

The University of Nottingham is home to the DH Lawrence Resource Centre and Manuscripts & Special Collections is home to a large quantity of primary sources relating to Lawrence and his work, including copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover – censored and complete versions. Information about DH Lawrence and our related holdings is available from our website.

A trailer for the new BBC version is available here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p030ndy7/preview-lady-chatterleys-lover-trailer

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply