June 11, 2015, by Kathryn Steenson

The First Cut is the Deepest

The worst experience in Charles Cullen’s young life was very nearly overlooked. The volume in which it is recorded, Uhg O 1/1, is a Treatment Book, and is unremarkable to look at. The brown binding is battered and the pages are covered in the scrawling handwriting of an 18th century doctor, complete with ink blobs and baffling Latin medical abbreviations. It was used almost daily between 1794 and 1801 by a doctor to record the details of his patients; the pills, potions and procedures he prescribed; and the outcome (patient discharged or died). I came across it whilst looking for material from our medical collections to use in a seminar. Many lecturers ask us to provide sessions on archives and research to postgraduate or final-year undergraduate students, most of whom have never used primary documents before.

I came across it whilst looking for material from our medical collections to use in a seminar. Many lecturers ask us to provide sessions on archives and research to postgraduate or final-year undergraduate students, most of whom have never used primary documents before.

Often our choice of display material is guided by the topic of the class, but this particular session was a general introduction to archives. Although this is a good example of a working document, it wasn’t created as either a tool for historical research or as an object of beauty. The catalogue entry mentioned that the binding was fragile (hence it is kept in a custom-made box, see below) and my concern was that displaying it would damage it further.

Our medical collections are extensive and include documents as diverse as 17th century medicinal recipes for curing the plague, to plans of the medical school from the 1970s, so there was plenty to choose from. The entry for poor Charles Cullen of Eastwood, however, managed to do something that a generic plague remedy couldn’t: to remind people that archives tell the stories of real people.

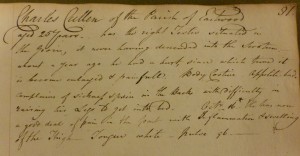

Nothing is known about him except what is recorded in the Treatment Book (see image below). Cullen was 25 and lived in Eastwood. Although we don’t hold parish records here, a very quick check of an online baptism index reveals a Charles Cullen was baptised in 1771 in Oxton, about 15 miles away, but we can’t say for sure that this is him. A year prior to his seeking medical help, he ‘had a hurt’ – presumably some injury – which had resulted in a worsening pain and swelling in his back, thigh and groin. His appetite was poor, his body ‘costive’ (i.e. constipated), and the pain was so bad he found it difficult to raise his legs to get into bed. On October 16th, his pulse was recorded as 96 beats per minute, which is slightly towards the high end of normal for an otherwise fit young man.

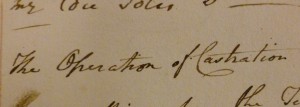

Cullen’s suffering for the next month must have been unimaginable. The tinctures and other remedies prescribed by his doctor did nothing to cure him. Surgery in the 1790s was a last resort. Mortality rates were high, anaesthesia non-existent, and pain relief woefully inadequate. On the 7th November, though, Cullen’s case notes read thus:

“The Operation of Castration was performed this morning and on cutting open the Testis after the operation it was found to be in a perfectly schirrous [hardened] state with an appearance of purulency [pus] at the inferior part.”

It’s easy to tell which students are paying attention in class by their facial expressions.

Some asked further questions, but unfortunately we don’t know for certain what happened to him, as shortly after, Cullen disappears from the medical records as suddenly as he appeared. He was ‘discharged for non-attendance’. Another quick check of the online burial index shows no entry for Charles Cullen within the next few years. The index isn’t complete but we can probably assume that he survived and chose not to return to the doctor – and who could blame him?

More information about our medical and health collections is available on our website. To discuss classes, email us at mss-library@nottingham.ac.uk.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply