June 3, 2015, by Kathryn Summerwill

How does it feel now you’ve won the war?

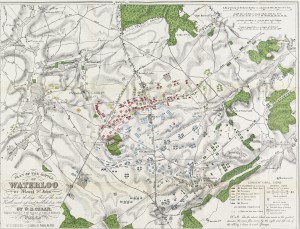

W.B. Craan, Plan of the battle of Waterloo, or, Mount St. John (Brussels, 1845)

From Special Collection Pamphlet DC244.5.C7

Guest blog by Dr Richard Gaunt

It’s the name of a bridge and a railway station in London, an island in the South Shetland Islands, several townships and cities across Australia, a region in Ontario, Canada and – for good or ill – the title of the most famous song ever to have won the Eurovision song contest.

It is this and all these things and yet the word Waterloo only entered the public consciousness two hundred years ago after a battle was fought to rid Europe of the menace of Napoleon Bonaparte forever. A battle which, today, has largely lost its hold over the popular imagination.

Things were very different during the nineteenth century. On the morning of Monday 19 June 1815, Wellington entered Brussels in the full knowledge that, the day before, his multi-national army of Prussians, Netherlanders, British and Germans had dealt Napoleon a decisive blow, dashing the Emperor’s hopes of a crushing victory over his European opponents.

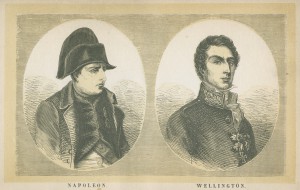

Napoleon and Wellington, frontispiece from Edward Cotton, A voice from Waterloo (5th ed, 1854). From DC241.5.C6

The fortunes of war sent Napoleon and Wellington’s lives in different directions. Bonaparte ended his days in isolation on the remote South Atlantic island of St Helena, far from the scene of former glories. Wellington, by contrast, went on to garner every title, office and distinction which the combined European powers had the power to bestow upon him, living out his years as an elder-statesman and the victor of Waterloo.

Naming the battle after Waterloo, the town where Wellington had his headquarters, proved a more controversial choice than many people now realise. The French argued that the battle should be named after the village of Mont St Jean, which was close to the ridge upon which Wellington drew up his combined forces and faced Napoleon.

However the Prussians, who famously provided crucial (some would say decisive) military assistance, late in the afternoon of Sunday 18 June, preferred the evocative name ‘La Belle Alliance’. This was the name of the inn at which Wellington and von Blücher (the Prussian commander) met in the closing stages of the battle.

Even Wellington’s despatch, the official account of the battle, which was begun in Waterloo, was completed in Brussels. By mid-July, the British press were still debating the competing merits of different names, though it was Wellington’s dislike for ‘La Belle Alliance’ which seems to have carried the day. By the time that a ‘Waterloo Medal’ was issued to all participants in the battle (regardless of rank) in 1816-17, the name was firmly established in the public consciousness. Thereafter, veterans were known as ‘Waterloo Men’.

Wellington’s annual dinner to his fellow commanders, held at his London home Apsley House each ‘Waterloo Day’, meant that the name became fixed in the social and political calendar.

However, after Wellington’s death in 1852, with veterans beginning to pass away, the fixed status of Waterloo lost its lustre in the public imagination. Britain’s ignominious military performance in the Crimean War (1853-56) offered a stark contrast with the close-run victory achieved forty years before. By the time that Waterloo’s centenary approached, in 1915, the country was embroiled in a far heavier conflict ‘in Flanders fields’.

In the century since World War 1, Waterloo has fallen into abeyance as a historical moment, overshadowed by the collective horrors of the twentieth century’s far-flung killing fields. Yet Waterloo’s power to upset contemporary political friendships has been marked in recent years, as the bicentenary crept ever closer.

In 1994, more than one French visitor was galled by the choice of Waterloo Station as the original terminus for Eurostar. Ten years later, on the centenary of the Anglo-French ‘Entente Cordiale’, Windsor Castle’s ‘Waterloo Chamber’ was temporarily re-named the ‘Music Room’ for a visit by President Jacques Chirac.

During the same period, Waterloo has been more recognisable as song lyrics, with The Kinks’ 1967 hit ‘Waterloo Sunset’ (referencing Waterloo Station) and ABBA’s 1974 blockbuster ‘Waterloo’, leading the way.

As Waterloo’s bicentenary approaches on 18 June, the battle’s power to divide opinion has continued to be reflected in media coverage highlighting present-centred political battles. A good example was the French veto over plans for a specially-minted Belgian Euro to mark the occasion.

By contrast, in 2013, the British government committed £1m towards the restoration of Hougoumont, the farmhouse whose successful defence contributed to the outcome of the battle. The first residential visitors are due to arrive this summer.

In a year of significant historical anniversaries, many of which are focused on Britain’s contrasting military fortunes (Agincourt in 1415, Gallipoli in 1915, Dunkirk in 1940, VE Day in 1945), Waterloo’s bicentenary is particularly important.

The centenary was, understandably, passed over silence. Nevertheless, situated as Britain now is in relation to Europe, the bicentenary may be a good moment to reflect on the fact that the battle itself represents a moment of genuine European collaboration.

This guest blog was written by Dr Richard A Gaunt, Associate Professor in British History at the University of Nottingham. He has curated the exhibition Charging Against Napoleon: Wellington’s Campaigns in the Peninsular Wars and at Waterloo which runs at the Weston Gallery, Nottingham Lakeside Arts, until 6 September.

Waterloo Day 2015 is being commemorated at Lakeside with a lunchtime talk: ‘From the Ballroom to the Battlefield: British Women and Waterloo’, and a special evening concert by the New Scorpion Band. Contact the Box Office on 0115 846 7777 to book your place at either of these events.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply