May 8, 2015, by Kathryn Steenson

A General History of Elections

From online voter registration to fixed Parliamentary terms, this General Election has seen a few ‘firsts’. In this post, we take a very quick tour of elections through the ages.

A dull campaign?

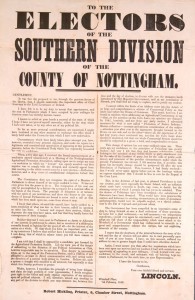

The art of eye-catching election addresses – the leaflets prospective parliamentary candidates send to people in the constituency – took a while to catch on, as this election poster (Ref: Ne C 4584) ‘appealing to [the] suffrages’ of the electors in South Nottinghamshire shows. It was displayed in public as part of the unsuccessful campaign by Lord Lincoln (later 5th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne) in the 1846 by-election.

Many householders consider election leaflets junk mail, but instead of putting them in the recycling bin, why not send them to the University of Bristol Library Special Collections? They accept election material from any constituency and party, and their collection covers every British General Election since 1892.

Not-so-secret ballot

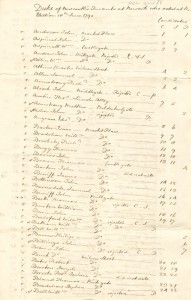

Until 1872, there was no such thing as a secret ballot. This list of tenants of the Duke of Newcastle (Ref: Ne C 4505/1) not only shows who voted in the 1790 Newark Election, but also the candidate they voted for. The letters above the columns are the candidates’ initials: William Crosbie, John Manners Sutton, and William Paxton.

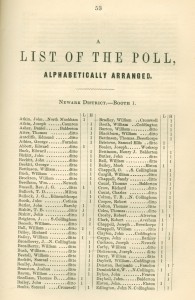

Supporters of the secret ballot objected to the influence, sometimes bordering on intimidation, that landowners and employers exerted over voters. Opponents insisted that elections were public and that the voting record ought to be open to inspection. It did not get much more public than the Polling Books, such as this one for the South Nottinghamshire election in 1846. The first 53 pages contain published versions of the speeches delivered prior to and at the election, and is followed by alphabetical lists of voters and whether they voted for the Earl of Lincoln (L) or the eventual winner, Thomas Thoroton Hildyard (H). When Poll Books became defunct after the introduction of the secret ballot, the main public record of voters became (and remains) the Electoral Registers.

Hustle and bustle

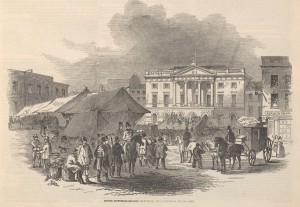

Hustings still survive today as a means for the electorate to interact with and quiz candidates standing for election. Despite increasing urban populations and expansion of suffrage making them difficult in towns, in 19th century hustings, temporary structures were erected at the time and place of an election, and prospective candidates were publicly nominated and made speeches to the assembled crowds. Candidates could be nominated or decide to withdraw throughout these proceedings, right up to (and occasionally beyond) the time the official polling began, basing their decision on the cheering, jeering, and informal show of hands of support from the crowds. This image from ”The Illustrated London News” depicts the hustings at Newark during the South Nottinghamshire election, 1846.

For more information about these and many other documents we hold, or to book an appointment to see any of them, please visit our website. You can also follow us on Twitter @mssUniNott or read our newsletter Discover.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply