April 20, 2016, by Harry Cocks

Drama and Politics in the House of Commons

On 2 May 1997, after suffering a heavy election defeat at the hands of Tony Blair, the outgoing British prime minister John Major told the assembled media on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street that ‘when the curtain falls, it is time to get off the stage’, Richard Gaunt writes. There could hardly have been a better illustration of the theatricality of modern political life. Today, it is a commonplace to deride the over-presentation of British politicians, with their (ex-journalist) special advisers, press officers and media training, but as I argue in my latest publication, ‘Sir Robert Peel as Actor-Dramatist’, the close relationship between politics and theatre originated in the first half of the nineteenth century. The proximity between Parliament and London’s theatre-land and the close association between politicians and actors was already established by the eighteenth century, with the dramatist Richard Brinsley Sheridan also proving himself to be an influential Whig MP in the 1790s. Likewise, the high media profile given to royal actress-mistresses like Mary Robinson (the famous ‘Perdita’) and Dorothy Jordan, ensured that the two worlds overlapped in the public consciousness.

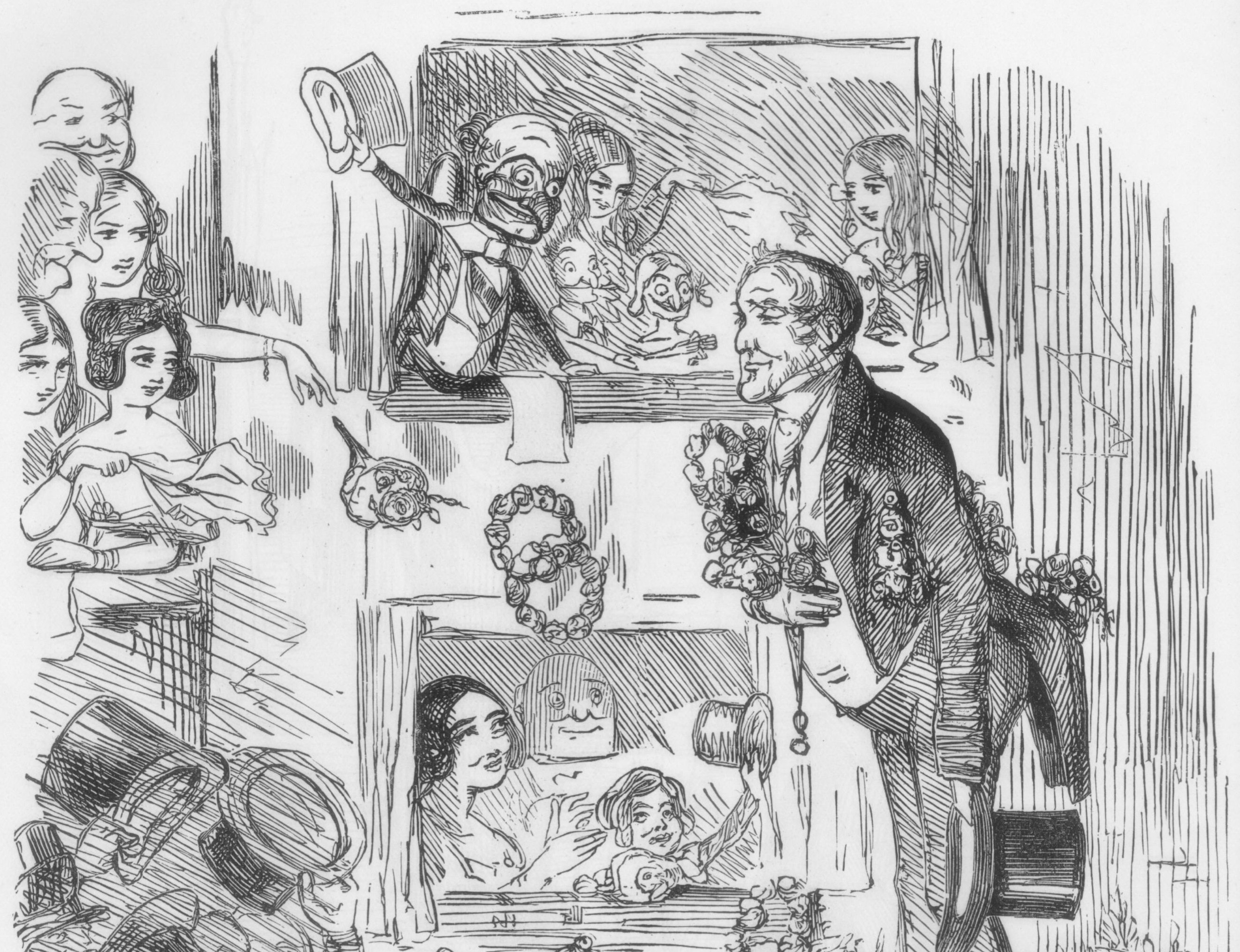

On first glance, the Conservative politician Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850), who rose to prominence in the era of great dramatic oratory in the Commons, would seem to be an exception to this rule. Peel’s penchant for dry, factual detail, and his conscious exclusion of classical oratory and Latin tags would seem to exclude him from the list of parliamentary dramatis personae of the age. Yet at moments of personal significance in Peel’s political life, his oratory assumed a form which was both intensely (some said irritatingly) personal and, ultimately, melodramatic. These habits in Peel’s mode of parliamentary delivery were picked up by the new breed of parliamentary sketch-writers spawned by the burgeoning newspaper press – their early number included a young Charles Dickens – and in the visual satires of the day. Even cartoons which, on first glance, looked unequivocally complimentary towards Peel – such as Punch’s ‘Manager Peel Taking his Farewell Benefit’, published at the time of the Repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, contained deeper meanings which relied on the audience’s understanding of contemporary theatre actor-managers and their habit for self-aggrandisement. Yet Peel’s example of a business-like style of presentation was not lost on his successors. Gladstone, a commanding parliamentarian, was a keen patron of the theatre, whilst Disraeli – whose early attempt to storm the Commons with a flashy oratorical style proved a major let-down – learned from Peel’s example. In spite of helping to foment the opposition which ended Peel’s political career, Disraeli emulated his ability to ‘play on the House of Commons like an old fiddle’.

Richard Gaunt, ‘Sir Robert Peel as Actor-Dramatist’ in Politics, Performance and Popular Culture. Theatre and Society in Nineteenth-Century Britain edited by Peter Yeandle, Katherine Newey and Jeffrey Richards (Manchester, 2016), pp.216-36.

http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9780719091698/

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply