September 1, 2020, by Richard Bates

Ann Milne – A Nottingham Army Wife who Nursed in the Crimean War

Our latest guest post comes from David Stewart OBE, a former head teacher and champion of the Nottingham arts scene and local history.

This post discusses the Crimean War experience of Ann Milne, an army wife from Nottingham. Along with previous posts by Darcie Mawby on nurses and Sarah Topliss on Dr Edward Wrench, it forms part of a developing series of blogs describing the experiences of Crimean War participants connected to the East Midlands.

“Few women have seen so much of the horrors of war”

On Monday 30 March 1908, Mrs Ann Milne – the only female member of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Indian Mutiny and Crimean Veterans Association – was buried with full military honours in the Nottingham General Cemetery.

The Nottingham Evening Post recorded that this was the first occasion on which military honours had been paid at a woman’s funeral. “Crowds of people thronged the cemetery and lined the streets from 21, Westwood Road, Sneinton to the place of internment,” it wrote. “Non-commissioned officers of the Robin Hood Rifles bore the coffin, which was covered with the Union Jack. The coffin was carried by Col. Sergeant Foster, Armour-sergeant Skinner, Sergt. Stanley and Sergt. Johnson and on top of it there rested wreaths from the Nottingham Association and from neighbours…” Around 70 surviving local veterans attended wearing their medals. A local veterans association sent a magnificent wreath, as did the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars, Colchester. “There was hardly a dry eye in the multitude assembled,” the Post reported. The funeral was also reported in national and regional newspapers.

“Few women have seen so much of the horrors of war as Mrs Ann Milne of Nottingham”

– Westminster Gazette, 1 April 1908

So who was Ann Milne?

Originally from Loughborough, she was born in 1830 as Ann Dent, daughter of Thomas Dent, a lace hand, and his wife, Ruth. Ann’s mother died when she was three, and her father quickly remarried a single mother, Mary Cramp. Tragedy struck the family in 1846 when in the space of a month, Ann’s three young half brothers all succumbed to smallpox, which was rife in their part of Loughborough. The 1851 census shows Ann working in an Angola Hosiery warehouse. This was the firm of Cartwright and Warner, famous for its Angola yarn and Merino hosiery. The firm presented shirts at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

In 1852 the 8th Hussars were stationed at the Loughborough Barracks, with other parts of the regiment and the regimental band in Nottingham. This explains how Ann met, and the following year married Charles Milne, a private with the 8th Hussars, at All Saints Parish Church in Loughborough.

Charles Milne was born around 1821 in Rochdale, Lancashire, the son of an insurance agent. His grandfather, Richard Milne, was a lawyer who was often in debt and to the chagrin of Mrs Byron seriously mismanaged the Rochdale estates of her son Lord Byron. Charles started his working life as a butcher, but joined the 8th Hussars in 1841. He had a mixed career as a private and corporal, being promoted and demoted at different times. According to Ann, he was an orderly to Lord Seaton, possibly at the great military camp at Chobham in 1853.

Ann’s time in the Crimea

Our knowledge for Ann’s time in the Crimea comes from newspaper reports – which were syndicated to national newspapers – in 1906 when she was on parade in Derby, and of her 1908 funeral. However, it can be difficult to separate out the truth from the journalese in these reports, which are generally light on historical specifics.

Though some of the reports suggest that she was a nurse, Ann was not part of any formal nursing venture. Rather, she was part of an older tradition of soldiers’ wives accompanying their husbands on foreign ventures, at a rate of four wives per hundred men. The Crimean War was the last in which this practice was permitted. According to historian Helen Rappaport, somewhere between 750 and 1200 women went to the Crimean War in this capacity – compared to fewer than 250 who served in the formal nursing arrangements led by Florence Nightingale. Only childless women were allowed to travel (some of those who went would later give birth during the war). Those who went were considered lucky, since the government offered no financial support to those who stayed behind (the Royal Patriotic Fund was set up for this purpose in October 1854). Yet such were the horrors of the Crimean War that Rappaport estimates that “a good three quarters of the army wives never returned.”

Departure

When Britain declared war on Russia in March 1854, Charles Milne’s regiment, the 8th Hussars, was mobilised. According to Rappaport, thirteen wives of the 8th Hussars travelled out, including Ann Milne. Rather than travel via France as originally planned, in April 1854 the regiment sailed directly from Portsmouth to Koulali, Turkey on four ships: the Echunga, the Mary Ann, the Shooting Star and the Medora. Almost immediately, they re-embarked with all the horses for Varna in Bulgaria, where the British and French armies were stationed. The Hussars arrived in Varna in early June.

On arrival, the soldiers’ wives were afforded no status or support. Some women were employed as washerwomen, but a reporter from the Morning Chronicle noted the concerns of the men of the 8th Hussars for their womenfolk. “They get no quarters, and no measures are taken to enable them to keep up with the march of the light cavalry … Fancy the burning sun of Bulgaria, and a number of these poor creatures trudging behind the horses of the troop … No tents were allowed them; they were not quartered on the inhabitants of the village; they must shift for themselves, as best they may….” In a letter from an officer in Varna, widely reported in the British press, the Turks were said to “have it that the soldiers’ wives at our camps belong to the harems of our Generals” – though Rappaport writes that to the locals in Varna, the British army wives appeared “worn down, hardened and sexless”.

In mid-July, cholera struck the camps, decimating the troops and their wives. They were dying so fast that they were buried in blankets. When the Hussars moved inland to Jeni-bazzar at the end of July, disease followed them. Fanny Duberly, a soldier’s wife who kept a journal of her experience, wrote that “the burning, blistering sun glares upon heads already delirious with fever.” Many of the doctors were ill and there were scant supplies. Charles Milne himself fell ill with (an unspecified) fever; Ann nursed him back to health. Ann says that her husband was promoted around this time to hospital sergeant – but his records note that he was promoted sergeant on 24 October 1854, by which time the army was in the Crimea (possibly this was the date on which the promotion was confirmed). At the end of August, the Hussars moved back to Varna to begin crossing to the Crimea.

According to The Daily Telegraph, Ann “witnessed the horrors of Inkerman and the field of Balaclava, after the charges of the light and heavy brigades.” However, Charles’s medal had no clasps for Alma, Inkerman or Balaklava, suggesting that he was probably not in the Crimea during these battles. It seems likely that Charles, remaining too sick to fight, had been transferred to the army’s base hospital in Scutari, Turkey – and that rather than the battles themselves, Ann witnessed the thousands of wounded and very sick men being brought into the hospital in the winter of 1854-55. This is consistent with the newspapers’ reporting that Ann “assisted in the hospital work before even Florence Nightingale came on the scene” and witnessed Nightingale’s arrival at Scutari on 4 November 1854.

It is not clear what Ann was able to do at Scutari. She would not have been able formally to nurse the men, as the medical authorities did not permit female nursing prior to Nightingale’s arrival (and then only reluctantly). According to Rappaport, some 260 army wives ended up in the hospital, many of them by this stage widows, and often in a desolate state since no provision had been made for them. In January 1855, Nightingale assigned Lady Alicia Blackwood, an aristocratic volunteer, to establish an infirmary and lying in hospital for the army wives and their infants. Blackwood later recalled that she was able to hire “several of the respectable and industrious women [i.e. army wives], employing them both as nurses to the sick and as washerwomen to the house.” They were paid from private funds

According to the newspaper reports, Ann “remembers her husband being on the staff of Lord Raglan on the heights of Inkerman. “She witnessed the siege and fall of Sevastopol.” The reports also state that she was “with the wounded at Balaclava and in the trenches before Sebastopol.” This would suggest that before 1 February 1855, when Charles was promoted to troop sergeant major, he had recovered from his illness and returned to the Crimea – and that Ann had managed to accompany him (no mean feat, as the army sought to keep women out of the Crimea). In late January 1855, some 4000 English troops were on the Heights of Inkerman. The long and protracted siege, life in army camps and the prevalence of disease must have made life tough for Ann and the other wives, but we have no details as to what she was doing during this time.

With the fall of Sevastopol in September 1855, troops were dispersed. The 8th Hussars wintered at Izmit, in Turkey, which the Inverness Courier described as a “wretched rickety conglomeration of wooden houses”. Here Charles Milne came down with fever a second time. He was again sent to Scutari, and then invalided home. He returned to Ireland, where the regiment was based, and discharged in October 1856 as unfit for further service, owing to his enlarged spleen and general bad health. (An enlarged spleen is a complication of typhoid fever.) Ann later reported that she met Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales when the regiment returned, and that the Prince had shaken her hand. This would have been on 12 May 1856, when Queen Victoria travelled from Osborne to inspect the 8th Hussars at Portsmouth before their removal to Kingstown in Ireland. The Morning Chronicle noted that amongst the troops there were four soldiers’ wives, so Ann could well have been one of these. There were also 150 walking invalids, four omnibuses of those unable to walk, and litters of those being taken to UK hospitals.

For his service, Charles was awarded the Crimean Medal with the clasp for the siege of Sevastopol, and the Turkish War Medal.

Later life

Ann and Charles had no children. After the Crimean War they appear to have led something of an itinerant life. The 1861 Census recorded them living in North End Street, in the central Derbyshire town of Wirksworth; Charles’s occupation was given as Lock Up Keeper. In 1862 the terrible news came that Charles’s brother, William Lewis Milne had slit his throat on a train to Birmingham, leaving a young son.

Charles became a publican, running the Red Lion at Kegworth from 1868. In 1871 the Milnes took on the Black Horse Inn in Aylestone in Leicestershire, which they ran until 1877. This was an old public house, which apart from parlours and five bedrooms had a large clubroom, which could seat 100 diners. By 1881, Charles was retired, and the couple were back living in Nottingham, at 3 Rye Hill Terrace in The Meadows. The 1891 census shows them living in Manchester, with Charles working as a caretaker, but they must have returned to Nottingham, as Charles died there at 27 Victoria Place in 1893. In his will he left £126.1s.

In 1894, Ann remarried, to Edward Jacques, a widowed insurance agent aged 71. But by the census of 1901 the couple were living apart in Nottingham. Ann was staying with Emma Hickling at 68 Flewitt Street in St Ann’s. Emma’s stepfather was William Cramp, the brother of Mary Cramp, Ann’s stepmother. Edward Jacques died in 1903.

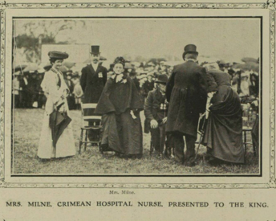

Ann Milne being presented to King Edward VII, 1906. London Illustrated News, 7 July 1906, p. 12.

Ann reverted to being called Ann Milne, and embraced her association with the Crimean War. On 28 June 1906 veterans from Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire met in Derby in the presence of King Edward. The King noticed Mrs Milne sitting amongst the veterans and asked who she was. He was told she had been a nurse first at Varna and then at Scutari before the arrival of Florence Nightingale. The King asked for her to be presented, and Ann presented him with a rose, which he wore for the rest of his visit.

The Nottingham and Notts Crimean & Indian Mutiny Association

That we know anything about Ann Milne is entirely due to the establishment of the Nottingham and Notts Crimean & Indian Mutiny Association in 1900. Seventy-two Crimean and Indian Mutiny pensioners registered in the first year. By 1906, 131 had appeared on the books. The Association originated in a campaign to raise money to give a Crimean War veteran a proper funeral. It was soon apparent that many other veterans were destitute, on poor pensions and with the prospect of a pauper burial. In 1900 a dinner was held at the Mikado Café, on the 46th anniversary of the Battle of Balaclava, for three men who took part in the Charge. The Association, mainly led by Mr Henry Seelby Whitby, a future Lord Mayor of Nottingham, aimed to ensure proper military burials for veterans, campaign for increased pensions, provide uniforms, and replace medals which some veterans had been forced to sell. Annual dinners were arranged including one in October 1904 at the Arboretum Rooms to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Balaclava. Sir Jesse Boot, later Lord Trent, provided the “Dorothy Boot” Homes at Wilford. In 1904 the association had secured at plot at the General Cemetery for the internment of veterans.

It was to this Association that Ann turned to for support. In 1906 they arranged for her to receive a pension of 7s a week from the Royal Patriotic Fund. In 1907 Ann joined a group of veterans at a fundraising matinee at the Theatre Royal and the Nottingham Express noted the presence of “Mrs Milne, who was a nurse in the Crimea.” The Association folded in 1937, but the year before it had arranged for a memorial window to be erected in St Mary’s Church, Nottingham.

The Veterans Ground in the General Cemetery, Nottingham. Photo: David Stewart

In search of Ann’s grave

With all the pomp and ceremony around her funeral, one might imagine that Ann’s grave at Nottingham General Cemetery would be easy to find. Yet when I began looking, I could find nothing. It was only after researching her life more thoroughly that I found she had remarried and was actually buried as Ann Jacques. Not only is there no headstone, but also the burial records do not indicate a place of burial. Her grave number is given as 15110, but locating graves in the Cemetery is not easy. The Nottinghamshire Family History Society transcribed the headstones in the Cemetery in 2003, but did not plot on them on a usable grid. The City Council has entered into deal with the Deceasedonline website, which charges £5 a time to locate a grave on a map which is not easy to navigate! But for Ann Milne/Jacques, no location is given. From discussion with the City Council’s memorial technician, we know that the grave is in S16 section. All that we know for sure is that she is buried with Charles Milne, her first husband and Lucy Ratcliffe, her elder sister. Also in the grave is Clara Clarke, aged 81 who was a friend of Ann’s, and Harriet Lufkin, aged 9, who was born in Essex but for whom I have not been able to establish a link to Ann Milne.

The Veterans plot at the General Cemetery, near the Waverley Street entrance. Photo: David Stewart

Further Reading

The records of the Nottingham and Nottinghamshire Crimean and Indian Mutiny Association are held in Nottinghamshire Archives.

The lead image is from the Daily Mirror, 31st March 1908, page 9.

—

Blackwood Lady Alicia. (1881). A Narrative of a Residence on the Bosphorus throughout the Crimean War. London: Hatchard.

Kelly, Christine (ed.) (2007) Mrs Duberly’s War. Oxford: OUP.

Moore, Doris Langley. (1974). Lord Byron Accounts Rendered. London: John Murray.

Rappaport, Helen. (2007). No Place for Ladies: The Untold Story of Women in the Crimean War. London: Arum.

David – Well researched ! You have fund a great story and link to FN’s work in the Crimea War. Its also a good link to Nottingham. I enjoyed reading it. Thank you again for taking the time to research this ! John W