May 7, 2020, by Richard Bates

Nursing Lives in the Crimean War

This post comes courtesy of Darcie Mawby, a second year PhD student at the University of Nottingham working on gender, conflict and identity in women’s accounts of the Crimean War, c. 1854–56. It is based on recent research conducted at the National Archives in Kew.

[Crimean War. Women nurses tending wounded soldiers as “woman’s mission”. Lithograph by J. A. Vinter, 1854, after H. Barraud. Wellcome Collection.]

It’s rare to hear about the lives of many Crimean war nurses. Even in the most recent publications, such as Carol Helmstadter’s Beyond Nightingale (2019), most highlighted accounts are those of nurses from early training institutions such as St John’s House, members of religious nursing sisterhoods, or lady nurses – plus of course the exceptional example of Mary Seacole. But there are 218 women listed on the register of “Nurses sent to the Military Hospitals in the East”, and hundreds more applied. Who were they? What motivated them to become nurses? What were their social backgrounds? The file of nursing applications, held at the National Archives in Kew, contains an abundance of fascinating stories that provide insight into the daily lives of nineteenth-century women and nurses.

Florence Nightingale left England with thirty-eight nurses in October 1854, heading for the hospital at Scutari Barracks in Constantinople. Newspaper advertisements were placed soon after by Lady Canning and Elizabeth Herbert – well-connected figures who knew Nightingale from serving on the committee of the Establishment for Gentlewomen During Illness, which Nightingale ran in 1853–54 – to organise further parties to serve in other newly established hospitals in Constantinople and the Crimea.

Applications flooded in. They came from women of all ages and classes, from all over Britain, Ireland, and beyond – there was a letter full of patriotic sentiment from Isabel Braide, a British woman living in New Orleans, who begged to be sent as a nurse. There were also occasional applications from men to work as cooks, doctors, or chaplains. The applicants’ motives varied. Some cited Christian and patriotic duty; some wanted to put their past experience of nursing, travel, or military life to good use; and some took the opportunity to appeal to the ladies’ benevolence for assistance. One woman, Mary Ann Brown, in her letter asking to be hired, recounted the mistreatment and desertion she and her children suffered at her husband’s hands.

Applicants had to meet certain criteria, and no nurse was sent without training. Many lower-class women who were appointed were experienced in hospital work. Susan Cator, for example, had worked at the London Hospital for eleven years. She was a senior nurse in the surgical ward when she was appointed to go to the warzone in August 1855. Despite the emphasis on experience, “character” was at least as important in the selection process. Nursing as a profession in general, and paid nurses in particular, had a negative reputation in the 1850s. No woman was sent who was not deemed “respectable”, a status ascertained through multiple references – from medical professionals or clergymen, if possible – and an interview with the overseeing ladies. Sobriety, good temper, activity, and honesty were especially valued. Cator nearly lost out on her appointment when an old accusation against her of drunkenness came to light. She was redeemed when multiple colleagues leapt to her defence, stating that a disgruntled former nurse had falsely accused her. Another woman, Mary Anne Fabian, was less fortunate. When she arrived at the train station acting strangely on the morning of her planned departure for Constantinople, she was dismissed immediately for intoxication. She wrote to explain that the impression of drunkenness had been caused by toothache remedies she had taken, but it was too late – the ship she should have been on had sailed, taking her luggage with it. Given that the medicines Fabian used were chloroform and brandy, it’s no wonder she acted out of sorts!

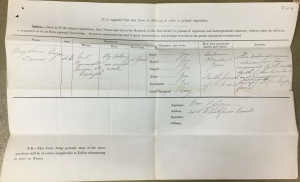

Extract of a “Testimonials Form” for Mary Anne Boyer Davies, who worked at Koulali Hospital April–June 1855. National Archives, Nurses Testimonials, WO 25/264/844. Of interest are the desired character traits – sober, honest, cleanly, active, intelligent, good-tempered – and the note: “N.B.—This Form being general, some of the above questions will be of course inapplicable to Ladies volunteering to serve as Nurses”.

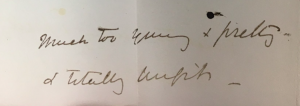

Personal circumstances were also a consideration. Women in their twenties were consistently deemed “too young”; they were too inexperienced and innocent for work in a military hospital and considered to pose too much temptation to soldiers. Many women applied to be nurses to be nearer to husbands, brothers, or sons serving at the front. Only four soldiers’ wives were accepted: three as nurses, one as Nightingale’s housekeeper. Notes written on the unsuccessful application of Anne Adams, whose husband was in the 28th Regiment, hint why there were so few: “we have been obliged to decline sending soldiers’ wives from the jealousy of their husbands & the quarrels it entails”. Such personal attachments could directly complicate the work and reputation of the nursing mission. One nurse, Martha Clough, earned notoriety after she ran away from the General Hospital in Balaclava to join the field hospital of the Highland Brigade, apparently in order to find the 79th Highlanders, the regiment of her love interest. Clough herself later succumbed to disease; one of thirteen registered nurses to die while serving.

Note on the unsuccessful application of Mrs Millington, aged 22: “much too young & pretty & totally unfit”. National Archives, Nurses Testimonials, WO 25/264/2386

Reputation was a constant concern. In the wake of Nightingale’s departure, nursing wounded soldiers was deemed by many who wished to follow her example to be one of the most noble of Christian causes. This is the image of Crimean War nursing that was quickly picked up by the popular press, and that is remembered today. However, female military nurses were considered an experiment, and Victorian social concerns imposed rigid constraints. Not only was there a backlash against nurses’ presence in military hospitals from many doctors, but applicants could face disapproval from their families. For this reason Mary Munro, a trained nurse who was ultimately sent to Smyrna Hospital, hid her application from friends and family – one of many to do this. Elizabeth Eager – another trained nurse – was convinced to withdraw her application by her sisters, who vehemently opposed the idea of her working in a military hospital.

Emily Kingston: Case Study of a Nottingham Nurse

While transcribing these applications there was one that stood out. I came across the name of the building housing my own History department at the University of Nottingham, “Lenton Grove”. I hadn’t given any thought to the history of Lenton Grove – a listed eighteenth-century building – so imagine my surprise when the name cropped up on an application from Emily Kingston, who lived there in the 1850s.

Lenton Grove, now on the University of Nottingham main campus, May 2020. Kingston’s old house has been converted into academic staff offices. Photo: Darcie Mawby.

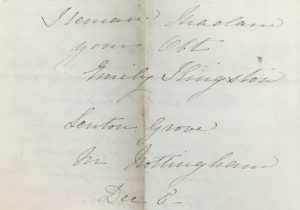

Kingston, a middle-class woman of 32, wrote to Elizabeth Herbert in December 1854 that,

“it has been for a long time past my earnest desire to join the nurses sent out to the Hospitals in the East, and having obtained my mother’s sanction to my so doing, I take the Liberty of addressing you to inquire if any additional nurses will be sent out”.

Kingston stated her willingness to submit to rules, mentioned her good health and that she “had some experience in sick rooms”. She also named respectable gentlemen as references, including Adjutant General Sir George Wetherall, and two uncles, both reverends. All proved favourable, as Kingston was sent to Smyrna Hospital in March 1855.

Her willingness to learn was important. Promising applicants lacking in experience were given training in London hospitals or at St John’s House, though there was little uniformity in this. Emily Kingston had already entered the hospital in Nottingham when she made her application in December, and so had several months’ preparation by the time she left for the war zone. Another woman, Mary Tattersall, had only just begun her training at Westminster Hospital when Kingston departed, but was herself sent out a mere three weeks later.

Emily Kingston’s character was noted on the register of nurses to be “exemplary and well suited in every way”, and one of her reference letters described her as “one in one thousand”. Her age and circumstances also worked in her favour. As an unmarried, middle-class woman of 32, Kingston could devote her time to charitable causes. She, like other “ladies”, gave her services gratuitously, but she also made application on behalf of her family’s cook, Anne Suter, aged 35, to go as a paid nurse. In doing so, Emily drew attention to Anne’s own nature as “perfectly respectable, sober, trustworthy, an excellent cook and a truly kindhearted and good tempered woman”. Suter was engaged as a cook at Smyrna Hospital, and her salary of 16 shillings per week – higher than the meagre 10 shillings for nurses – testifies to the truth of Kingston’s words.

Kingston and Suter fulfilled, in two different ways, the lady organisers’ aim to recruit the “right class” of nurse. Unquestioned superiority was given to the more inexperienced women of higher social rank, like Kingston, whose moral character was deemed sufficient qualification for them to preside over the paid nurses. Although those paid nurses were vetted, not all were appreciated like Suter. A number of the nurses from St John’s House, who went in the first party, were dismissed for “incompetency” as military nurses.

Letter by Emily Kingston, National Archives, Nurses Testimonials, WO 25/264/1995

There was far more diversity among Crimean War nurses and applicants than I have outlined here, and certainly more than the popular image of Florence Nightingale and the lady nurses suggests. The selection and work of military nurses were fraught with Victorian concerns about class, propriety, and female morality. But the nursing mission also provided an unprecedented opportunity for women to train, work, and travel for a good cause. Emily Kingston worked at Smyrna Hospital until it was “broken up” in December 1855, as the war neared its end. Anne Suter continued to work until May 1856, after peace had been declared. They, like numerous other women from housemaids to noblemen’s daughters, sought rewarding work and new experiences in nursing.

Sources and Further Reading:

The National Archives, Nurses Testimonials, WO 25/264.

British Library, Charlotte Canning Correspondence, Papers Relating to the Crimean War, Mss Eur F699/2/3.

British Library, Nightingale Papers, Vol. X, Add MS 43402.

Florence Nightingale Museum, Nurses sent to the Military Hospitals in the East (display item).

London Metropolitan Archives, Letters Relating to Nurses from St John’s House, H01/ST/NC/03/SU/A.

Helmstadter, Carol, Beyond Nightingale: Nursing on the Crimean War Battlefields (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2019).

Helmstadter, Carol and Godden, Judith, Nursing Before Nightingale, 1815–1899 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011).

McDonald, Lynn, Florence Nightingale: The Crimean War: The Collected Works of Florence Nightingale, Vol. 14 (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2010).

Summers, Anne, Angels and Citizens : British Women as Military Nurses, 1854–1914 (London : Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1988).

Excellent piece of research. Emily Kingston died at 3 Montpellier Terrace, Brighton on 7th November 1892. She left over £20,000. Executors were her sister Louisa and niece Isabel Charlotte Wheeler.

The family cook, Anne Suter is mentioned in Martha Nicol’s book Ismeer or. Smyrna and the British Hospital in 1855. She refers to her as Mrs Suter though she was unmarried. “Mrs Suter acted as cook at our quarters and very excellent she was. Not only was she was kind and obliging as a servant, but she was one who thoroughly knew her place, and was never above doing anything to assist us and add to our comforts in any and every way both at Boudjah and at the quarters.” I wonder what happened to her after the Crimean War?

Interesting to remember that at Lenton Fields near to Lenton Grove lived Catherine Turner, the cousin of Harriet Martineau who worked with Florence Nightingale.

In October 1856 a grand bazaar was held at the Mechanics Hall, Nottingham in support of the Girls’ Industrial Institution which was connected with the Ragged School. One stall was organised by Mrs Enfield and Mrs Eaton. The Nottinghamshire Guardian reporter noted, “We must not omit to mention that amongst the attendants at the stall of Mrs Enfield and Mrs Eaton was Miss Kingston, a lady who has distinguished herself alongside of Miss Nightingale, as a Crimean nurse.”

On the stall run by Lady Belper and Lady Sitwell were “two interesting prints of Miss Nightingale, contributed through Lady Sitwell, by Mrs Nightingale of Lea Hurst, one representing her attending the sick and the other on horseback, on the heights of Balaklava, attended by Mr Bracebridge.”

Note:Mrs Anne Enfield was the daughter of Matthew Needham who had built Lenton Fields (University Campus) for Mrs Catherine Turner, the cousin of Harriet Martineau. Her husband, William Enfield was the town clerk of Nottingham. Anne Enfield and Catherine Turner are buried together in the General Cemetery, Nottingham. Mrs Elizabeth Eaton’s husband was the manager of Wright’s bank. The Dowager Lady Sitwell, nee Sarah Stovin, was second wife of Sir Sitwell Sitwell and second wife of John Smith Wright, banker of Nottingham. She founded the Midland Orphanage for Girls in Lenton. She lived at Rempstone Hall, Nottinghamshire. Mrs Nightingale mentions being at Rempstone Hall in October 1843. On 10th October 1848 Florence writes to her father from South Villa, Gt Malvern in which she writes, “love to Ly Sitwell & Miss Stovin.”

“Sir, she was an angel, and worth her weight not in gold but in diamonds. Thousands who did come back to old England would never have reached here but for Florence Nightingale. She was a marvel – a regular soldier’s friend and one who thought about the wounded first and himself afterwards.” This recollection from an old soldier was recounted by Mr Whitby of the Nottingham Veterans Association, in his Appreciation in the Nottingham Evening News on the occasion of Florence Nightingale’s death in 1910. He was referring to Robert Holden of Beeston, who had been one of the party of six soldiers who had carried Florence NIghtingale when she became ill, taking her to the Castle Hospital. Whenever he referred to the “Lady with the Lamp” he would say “She was a grand lady to us soldiers, a regular mother, so kind so gentle, and we often wondered if she ever went to sleep, because she was always at work among the sick day and night. We were glad to hear of her recovery.” So who was Robert Holden?

Well he wasn’t Robert Holden at all but Robert Oldham, born c1832 in Beeston, Nottinghamshire.

He had enlisted in the Coldstream Guards in Grantham in 1853 but his name was put down on the roll of his regiment as Holden so he served under that name. He fought at Alma, Balaklava, Inkerman and Sebastopol, receiving the Crimean medal with four clasps and the Turkish medal. When he died in 1908 he was the only survivor in Nottinghamshire belonging to an infantry regiment in possession of four bars for the Crimea. He was wounded three times at Inkerman and later was severely wounded in the left foot. He would recount graphic tales of burying the dead after the battle of Inkerman.

On his return he was feted in Beeston and presented with a chair. In actual fact the event had been organised for Private Leivers of the 7th Fusiliers on 20th March 1856, but he did not arrive on the train at Beeston. Banners and a band were waiting at the station with a large crowd. Not wanting to waste the occasion, they fetched Robert Oldham who had returned some weeks before. They marched to the Commercial Inn and presented him with a chair. A speech was made in his honour, he returned thanks and the band played “God Save the Queen.”

We encounter Oldham later before the magistrates for pub brawls and poaching. He worked in the silk trade and had several children. He died 18th March 1908. His funeral left from the house of his daughter, Hannah Foulds at 29 Derby Street Beeston.

His quote “she was a grand lady etc. is sometimes credited as Robert Holden or Crimean Veteran.

Robert Oldham was my Great Great Grandfather on my Mum’s side of the family.

Great article source to read. Thank you for sharing this.