May 7, 2020, by Richard Bates

Edward Wrench: An Army Doctor in the Crimean War

This blog post is by Sarah Topliss, a volunteer citizen researcher who has in recent months been investigating the Wrench archive held by the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections. The archive contains some 32 boxes of letters describing Wrench’s life in the Crimean War, Indian Rebellion, and work for the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth and Baslow, Derbyshire after 1862.

[Image: Edward M. Wrench in Uniform of 12th Royal Lancers, 1862. UoN MSC Wr Ph 6, used with permission. ]

Dr Edward Mason Wrench (1833-1912) was the eldest son of the Rector of St Michael’s, Cornhill, London. Following an apprenticeship at St Thomas’s Hospital, he joined the army as an assistant surgeon. He served in the Crimean War (1853-1856) from October 1854 – a time when the army medical services were suffering appalling problems and an urgent recruitment of junior doctors was underway.

Initially, Wrench was stationed at the General Hospital in Balaclava, in the Crimea, and treated soldiers wounded in the Battle of Inkerman. From December 1854, he was on the front line serving in the trenches during the siege of Sevastopol. Wrench saw action at the capture of the quarries on 7 June 1855, the assault on the Redan on 18 June 1855, and the final offensive on Sevastopol on 8 September 1855. He demonstrated outstanding courage when treating patients under fire and was commended in despatches for his actions. Wrench received the Crimean medal and clasp, and the Turkish medal. He left the Crimea in July 1856, after writing over 400 letters to his family and friends back home in England. These letters paint an absorbing picture of the life of an army doctor in the Crimean War.

Treating the soldiers

The General Hospital in Balaclava – the field hospital for British troops where Wrench served on his arrival in the Crimea – was formerly a Turkish school. Housing 300 patients, it was situated on a hill above the town, only a mile and a half away from the Russian enemy. Wrench had charge of a ward containing 33 patients. He described his work there as ‘not hard but troublesome’. Medicines were in short supply; Wrench made all the pills for his patients using what he could scavenge from the old school, including the children’s slates and copy books. In letters home, he described the sick and wounded as ‘100% worse off than any sick in any hospital in England’. There was no opium or other essentials required for treatments of the time, like arrowroot or tea.

After his stint in the General, on 3 December 1854 Wrench joined the 34th Regiment of Foot in their trenches and encampments on the heights above Sevastopol – equipped with only two days of provisions and a blanket. Due to the shortage of supplies and horrendous conditions, he found it difficult to treat patients during the winter months, when many soldiers died of fatigue and starvation. Wrench’s letters explain that the soldiers received insufficient nourishment from their rations of salt pork, potatoes and green coffee beans. The soldiers spent twelve hours at a time in the trenches, returning to the camp cold and wet through. They then had to make a fire to cook their meat and brew coffee, before going to sleep on the damp ground covered only with a blanket (two if they were lucky). Wrench considered that this routine was enough to kill any man, adding that he had ‘rather underdrawn the picture’. He did his best for his patients, but they were dying of exhaustion and he had nothing to give them. Such conditions threatened the very existence of the army.

In early 1855, Wrench was put in charge of his own hospital hut for the sick, treating between twelve and twenty patients. By the beginning of March, the weather had turned fine and supplies had improved significantly. The field hospitals now received soup and oranges, as well as medicines. Wrench was finally able to spend some of the money his aunt had sent him to help the sick and wounded. He claimed one patient owed his life to this fund, after eating some eggs the money had purchased. Sadly, the warmer weather also brought with it cholera and Crimean fever. Wrench lost two of his friends to fever. Working closely with infected patients, medics faced a constant threat of contracting disease themselves.

In May 1855 Wrench was in charge of a hut for the wounded, with ten badly wounded men under his care. This work posed different challenges to treating the sick. Wrench was constantly tired – his sleep disturbed by wounded men in need of emergency treatment in the middle of the night. As the beds lay only a foot from the ground, continually bending down to treat the men gave him back problems. But he felt it was better than attending fever or cholera patients.

Wrench’s first experience of surgery in camp was assisting with the amputation of a Russian prisoner’s leg. The prisoner was lucky to be given chloroform, as at the time not all physicians agreed it was beneficial. Wrench doubted the amputation would be a success. However, the prisoner survived, and after a month was up and about the camp on crutches. Wrench described him as quite a character and an intelligent ‘lion of a man’. He did not want to return to Sevastopol or his wife, telling the interpreter that if his wife thought he was dead, ‘why undeceive her’. Instead, the Russian wanted to go to England as a prisoner of war, and learnt some English in preparation. Wrench wrote that when he was asked how he was, the prisoner would reply, ‘Quite well thank you’.

Life as an army medic

Medical officers were fortunate not to be exposed to the Crimean climate to the same degree as ordinary soldiers. Wrench had his own tent – and was very proud of it, including a detailed sketch in a letter home. He sank it three-foot deep to make it more spacious. He covered the floor with sand, decorated the walls with old newspapers and added shelves for storage. Wrench’s fellow officers were critical at first, claiming it would be too hot in the summer, but soon adopted his design. Later, a piece of ground four-foot square became Wrench’s garden. Other officers cultivated similar plots and Wrench enjoyed the camaraderie of friendly competition over whose was the smartest.

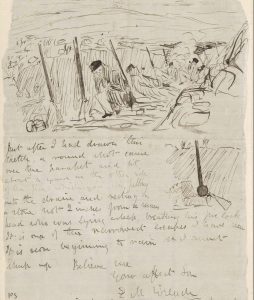

Wrench’s sketch of the inside of his tent, April 1855. UoN MSC Wr C 18/2, used with permission.

Possession of a horse allowed officers to transport their own supplies from Balaclava to the army camps. Wrench obtained a pony, which he named Punch. The pony had a mischievous streak, breaking loose and fighting with other ponies. To Wrench’s amusement, Punch had a habit of poking his head through the tent flap to see what was happening inside. When offered a biscuit, he would take the whole plate and throw it outside.

Medics on the front line risked great danger. Unlike the more developed trenches of the First World War, Crimean War trenches were more like shallow ditches, where men worked in shifts, marching there and back to camp for up to two miles in all weathers. Wrench had to take his turn in the trenches every fourth or fifth day. He found it particularly arduous when it rained, as he had to ‘sit in a pool of mud for twelve hours’.

Wrench had many life-threatening experiences in the trenches. In February the Russians fired directly on him – he believed it to be young artillery officers firing merely for practice – but to general amusement the only casualty was his friend’s trousers which were torn in the panic. However, when Wrench was fired on again on 16 March 1855 not everyone in his party was so lucky: a man next to him was shot right through the body, leaving an enormous pool of blood where he fell. On 14 April 1855, Wrench was writing a letter from the trenches while shot and shell flew overhead – a shot came over the parapet, landing ten yards from Wrench and two inches from another man’s head as he lay asleep. Wrench was also not safe from Russian fire while in camp. On one occasion, he was standing at the door of his tent when a Russian round shot flew directly overhead – he commented that he had ‘never been more frightened in the trenches.’ Had the missile fallen twenty yards shorter it would have hit the hospital, causing chaos and injuries.

The delay and uncertainty over taking the town of Sevastopol in summer 1855 were also psychologically disturbing. Wrench wrote that ‘going down to the trenches now makes you feel queer, the knowledge that the whole of the party you are marching with are almost certain not to return alive and that you may be one of those makes one think a good deal about death’.

Extract from a Wrench letter of 14 April 1855, including a sketch of men in the trenches in the siege of Sevastopol. UoN MSC Wr C 23, used with permission.

The Nightingale connection

The emergency recruitment of medics in the Autumn of 1854, when Wrench enlisted, also prompted the mission of Florence Nightingale as Superintendent of Nursing with her initial party of 38 nurses. Nightingale’s base was not in the Crimea itself but at the Barrack Hospital in Scutari, 300 miles away. Nightingale visited the Crimea in May 1855, arriving to find Balaclava harbour congested with ships and bystanders trying to catch sight of her. Nightingale toured the base and regimental hospitals and some of the trenches before Sevastopol. She made recommendations to improve the kitchens at the General Hospital and reorganise those at the Castle Hospital – before collapsing on 13 May 1855 from ‘Crimean fever’, thought to be the first attack of the brucellosis which crippled her for much of the rest of her life.

The news of this reached Wrench, who wrote home to his Mother on 14 May 1855 describing how Nightingale had been carried up to the convalescent hospital at Balaclava on a stretcher. Although the two had never met, Wrench expressed heartfelt admiration for Nightingale, saying she had saved many lives. He referred to the hostility Nightingale had encountered among some of the army medical command when he wrote that he was ‘disgusted with anyone speaking ill of her, they little know what she has gone through … the big surgeons may call her interfering, but the assistants stick up for her and as they were the men who did all the work at Scutari they ought to know best’. Wrench’s attitude indicates that the resentment towards Nightingale on the part of some senior medical officers did not extend to the ordinary army doctors, whose feelings of admiration more closely resembled the positive reputation Nightingale had already garnered among the wider public.

Further Reading

University of Nottingham, Manuscripts and Special Collections, Wr – Papers of Edward M. Wrench (1833-1912) of Baslow, Derbyshire, surgeon, 1837-1956.

Bostridge, Mark (2009). Florence Nightingale. London, Penguin.

Figes, Orlando (2010). Crimea. London, Penguin.

Shepherd, John (1991). The Crimean Doctors, A History of the British Medical Services in the Crimean War, Volume One, Liverpool University Press.

Small, Hugh (2018). The Crimean War. The History Press.

Florence Nightingale was an outspoken critic of British colonialism, arguing that the presence of the military in India, for example, was actually causing poverty and disease. She was in touch with members of the independence movement, and Gandhi wrote to her for advice. Could it be that she was also a critic of war, whether the Boer Wars or WW1 itself?