November 5, 2018, by Kate

Functional analysis: A simple worked example of a (fictional!) case

Functional analysis

Functional analysis is a model of psychological formulation designed to understand the functions of human behaviour. It has its origins in behavioural psychology. At its core, functional analysis assumes that all behaviour is learned, and that all behaviours serve some purpose. This applies equally to challenging behaviours (such as violence or self-harm) as to more socially acceptable acts.

The NICE guidelines describe functional analysis as “A method for understanding the causes and consequences of behaviour and its relationship to particular stimuli, and the function of the behaviour”. They recommend the use of functional analysis in the assessment of challenging behaviour in adults with autism spectrum disorder and learning disability. As with any formulation, one of the primary aims of a functional analysis is to guide interventions to help people. This might include things like positive behavioural support plans.

Functional analysis is a way of helping us to understand why someone is acting in a certain way.

So for this example, imagine you are a psychologist working at a medium secure unit. You have been asked to complete a functional analysis for Rob, who has been displaying regular verbal aggression since he came to the unit.

The case background

Rob is a 27 year old man, he has been diagnosed with a mild learning disability. He is currently detained in a medium secure unit, due to sudden outbursts of verbal aggression and, sometimes, physical violence.

Rob grew up with his mother in the countryside. He was an only child; his father was arrested after hitting his mother when Rob was aged 7. Rob’s mother has described finding his behaviour difficult to manage when he was younger, although she loved him very much.

Rob found primary school difficult. Teachers reported that he found it hard to keep up with the other children, and would ‘act-out’ when he got frustrated. As he got older, his behaviour got worse, including throwing things at teachers and hitting other children. He was eventually transferred to a special school and diagnosed with a learning disability. Rob first got into trouble with the police when he was caught stealing from a local shop as a teenager, he said that his friends had encouraged him to do this. His Mum has said that she thinks some of Rob’s friends were bad influences, as he started smoking to try and impress them. Rob started getting into fights and was eventually arrested after punching a stranger.

Rob’s IQ test (the WAIS-IV) suggests that he has some problems with processing speed. This means that it takes him more time to take in and process new information, and it may take him longer than most people to perform mental tasks. He had a relative strength in verbal comprehension, suggesting he has good skills with words and language.

An assessment of Rob’s adaptive functioning suggested that he had strengths in social skills and leisure activities. However, he had some deficits in communication and practical skills including self-care. He also has some problems with academic skills and limited independence and self-control.

Assessment

Our job is to try and work out what function verbal aggression is serving for Rob. In order to do this, we need to gather as much information as possible about the behaviour itself. We also need to know what happens immediately before and after. So we need to understand:

Antecedents

What is going on immediately before Rob is aggressive?

Behaviour

What exactly is the behaviour? We need a really clear description in order to be able to monitor and understand it.

Consequences

What happens immediately after the behaviour?

First of all we need to clearly define the behaviour. So rather than just the general term ‘aggression’ we need to think about what Rob actually does, and explain it in a clear and concise way.

There are lots of different ways to try and gather information, and we want our investigation to be as thorough as possible. So we use different methods to gather information:

Indirect observation – This means asking other people about the behaviour. In this case we might interview Rob himself and speak to nursing staff and people that work with him. There are some helpful (and free!) questionnaires that can help. A couple that I have found useful are:

- The modified overt aggression scale which helps to describe and categorise aggressive behaviour and monitor its frequency.

- The motivation assessment scale which asks an informant (observer) questions about a behaviour to try and work out the motivations.

There are several others though!

Direct observation – This means that we observe the behaviour ourselves, so in this case we might spend time on the ward so that we can watch Rob’s behaviour in different circumstances. People sometimes use ABC charts to record the antecedents and consequences of a behaviour of interest. There are lots of examples online, or you can make your own!

So, after gathering data from staff on the ward and completing our own observations, we start to realise that Rob seems to become aggressive more often in loud situations with lots of people present. We come up with the following information:

Antecedents:

- Social situations – Rob becomes verbally aggressive more often when other people are present

- Male staff present – This tends to happen when male staff are on duty

- Loud, noisy environment – This tends to happen at times of day when the ward is more noisy and busy (including mealtimes and medication times)

Behaviour:

- Rob stands up, raises his voice and swears at staff who are physically close to him

Consequences:

- Staff typically respond immediately by asking Rob to sit down, lower his voice and stop swearing (verbal de-escalation)

- Rob rarely responds to this, and so staff will then take his arm and escort him to his room or a lower stimulus environment

- Staff will then sit and talk to Rob about his behaviour

Functions of the behaviour

So, now that we have a clearer idea of what’s happening, we need to understand the function. We usually think about several plausible functions:

Attention

Gaining attention, affiliation or interaction with other people. For example, someone hurting themselves because they will then receive medical attention – this is positive reinforcement.

Self-stimulation

Gaining an internal positive feeling that is not dependent on other people. For example, getting a buzz from driving too quickly – again positive reinforcement, although sometimes called intrinsic reinforcement.

Tangible rewards

Gaining actual ‘stuff’ that someone wants. For example, if you give a child sweeties when he/she cries to try and get them to be quiet, they may be louder to get the sweeties! Again this is positive reinforcement.

Escape or avoidance

This is about finding ways to get away from (escape) or not be exposed to (avoid) unpleasant things. For example, a student not attending classes where they have to present as it makes them anxious – this is negative reinforcement.

So in Rob’s case, there are two functions that seem to make sense:

Escape – when he starts shouting he is removed from a noisy, social environment. We know from his case history that it sometimes takes Rob a bit of time to take in information, and that he generally has good social skills. So it makes sense that he might find busy noisy environments stressful, particularly when he is in social settings.

Attention – Another possible function is that when Rob behaves in this way he gets individual attention from male members of staff. We might wonder from his case history whether Rob has had positive male caring figures in his life, and so again this is a plausible function of behaviour.

Depending on the circumstances, it might be that we stop with this functional assessment, and use what we have found out so far to inform our treatment planning. However, there is another step we can take which is to manipulate the antecedents or consequences of Rob’s behaviour in assessment sessions to find out the primary function.

Functional analysis

A true functional analysis includes in some way manipulating either the antecedents or consequences of a behaviour, to see if this effects how frequently the behaviour is used. This is an experimental method which allows us to more confidently establish what is causing a behaviour.

This can pose ethical and practical challenges in secure environments, and throughout our practice we have to consider the safety and well-being of everyone.

So in order to get the best data, we could conduct an experiment to test the functions of Rob’s behaviour. This might include devising conditions where Rob is told off when he becomes threatening (attention), or is allowed to stop doing something he does not like when he becomes aggressive (escape). We would then monitor the frequency of the behaviour in each of these conditions (as well as a control condition). We would use this information to establish the primary function. However, in Rob’s case, this behaviour might cause distress for Rob or for other people, and so we have to think about how ethical this is.

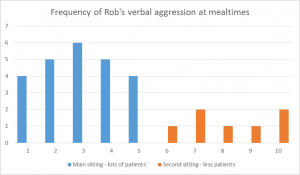

One alternative is to use something called naturalistic experiments. This means monitoring behaviour in circumstances that arise naturally. So in Rob’s case, imagine that in order to manage risk he is put on second sitting at mealtimes (meaning that he eats later, with fewer patients present). We know that one time he seems to become verbally aggressive is mealtimes. So we could see what happens if Rob eats with fewer other patients present, but the same number of staff. If the primary function is attention, then we would expect the behaviour to occur as frequently. If the function is to escape a noisy social environment, then we might expect the frequency of the behaviour to reduce.

So we monitor the frequency of Rob’s verbal aggression. We can see that when he is put on second sitting the frequency of verbal aggression decreases. So we conclude that the primary function is to escape an uncomfortable environment.

Applying our findings to treatment plans

Now that we’ve established the function of Rob’s behaviour, we have to design plans to try and reduce the behaviour and increase Rob’s well-being. There are a few different ways we can do this:

- We can consider environmental changes in order to reduce Rob’s exposure to stressful situations. This might include reducing Rob’s exposure to loud busy social environments

- We can think about alternative strategies Rob can use to communicate his distress, and work with him to develop these strategies – for example holding up a red card if he is finding a situation too difficult to manage

- We can consider the ways staff working with Rob respond to his behaviour, to ensure that we all respond in ways likely to reduce aggression.

Once we design our plans, it is really important that we continue to monitor the frequency of the behaviour to see if our plans are working!

Pros and cons of functional analysis

Pros:

- Leads clearly to treatment recommendations

- Can be used with people who struggle to express themselves verbally

- Has a great deal of research support – it works!

Cons:

- Focuses on a specific problem behaviour (the people we work with may have multiple presenting difficulties)

- Does not consider underlying factors which may be contributing to the need for the behaviour – e.g. if a behaviour reduces distress then functional analysis should be able to identify this, but it is not able to identify the underlying source of the distress, such as unresolved trauma.

Functional analysis can be an incredibly useful tool, but often it is part of a wider formulation. For example in Rob’s case, we might have successfully identified the function of his verbal aggression and be able to design interventions to reduce this. However, we might be interested in other aspects of the case. Rob’s father was violent, it might help to understand his early attachment relationships and associated core beliefs (or cognitive schema). It looks like social relationships come up a lot in this case, so we might also be interested in his social self-esteem and vulnerability to peer pressure.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply