February 13, 2007, by Peter Kirwan

Richard III: An Arab Tragedy (Al-Bassam Theatre) @ The Swan Theatre

The final ‘response’ play saw the hugely-respected Sulayman Al-Bassam theatre company coming to the Swan, presenting a reworked ‘Richard III’ that relocated the action to the contemporary Middle East, a world of oilfields, bickering clans, foreign policies and constant surveillance. It’s been hugely built up over the year, as a new RSC commission, and promised to be something very special.

After seeing it, I have to confess to feeling slightly underwhelmed. There was much that I found very exciting about the production, but equally much I found frustrating or simply not very good. I’m very interested to see what the press think tomorrow night, as it’s the kind of production which invites praise simply by virtue of its intent and cultural background. Yet intent can’t disguise much of what was sloppy about the production.

Actors stumbled over lines, interrupting each other in the wrong places and causing awkward pauses. Elsewhere, a vastly edited text (‘Richard III’ in under two hours!) meant that the pace varied wildly- key scenes were rushed through almost at a run, while other scenes slowed to a crawl. To me, it felt under-rehearsed, a close (though far better funded) sibling to the Young People’s Shakespeare back in September.

The play weaved together a mix of dialects and ways of speaking, reflected in the surtitles. At times, the translation closely followed Shakespeare’s text, the language being ‘high’ and poetical. At others, it was rewritten in a far more contemporary idiom, and at other points the text was completely new, filling in the spaces for this relocated play. While this was very interesting, it also meant the tone of the play varied wildly. As the person next to me commented, “Nobody would speak like this in Arabic”- characters jumped between everyday and exceedingly poetical forms of speech, with no obvious distinction between the types of scene that made this appropriate.

However, there was much to be admired about the play as well. The new setting made quite a lot of sense. Anne’s wooing now took place in a female mourning room, Richmond became the invading Allied Forces, trying to win the hearts and minds of the people, Richard’s reluctant acceptance of the crown took place on a TV debate show, with politicians and celebrities calling in, and the oil fields that Buckingham was promised became an important bartering tool as the country crumbled around Richard.

The most exciting things about this production came in the characters of Buckingham and Catesby. Catesby was her the servant of Hastings, who quickly entered Richard’s employ, playing his master and Stanley of against the court, leading the questions on the debate show, backing Buckingham in public orations, wielding a ready sword against Richard’s enemies and even offering to kill the Princes when Tyrrell was ‘unavailable’. After killing them, though, he entered a period of guilt-ridden atonement, singing a mournful dirge as he prayed for forgiveness, eventually leaving Richard alone on his horse.

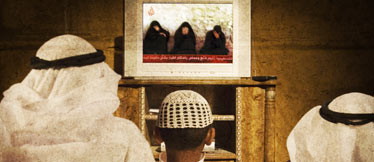

Buckingham was even more interesting. From the start he manned a bank of TV monitors with views of conversations around the palace. He was in constant communication with the American Ambassador, informing him as Richard’s rivals were picked off, and helping Richard ascend to the throne. A Frenchman, Buckingham here became a representation of the West interfering in the politics of the East to its own advantage. Amoral, in complete control of Richard and concerned only with obtaining the oil fields he had been promised, he had real power among the feuding locals, and Richard completely humbled himself before him. It was Buckingham who had possibly the play’s key speech, as he explained to Richard the machinations by which he could force any political play he wanted by simply signing the right things or setting the right events in motion. Asked again, “But HOW do you excuse all of these things?” he simply replied “Three words. War. On. Terror.”

The satire of the play was pointed. At one point, a news report stated that “Minister Hastings has been arrested on suspicion of treason. In related news, Minister Hastings was hanged this morning for treason, and his head interrogated in the square”. Using one of Britain’s lowest periods, Al-Bassam has found a great deal of relevance to his own time and place, and managed to include critiques both of Western foreign policy and on the political intrigues of the Arab World.

This play seemed to me to have more theoretical artistic value than was realised on stage. It could have been a fascinating and deeply moving production, with more careful editing and more rehearsal. As it stood, it was a flawed but deeply engaging look at an unfamiliar society through one of our most familiar stories, and I did enjoy it overall.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply