June 25, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

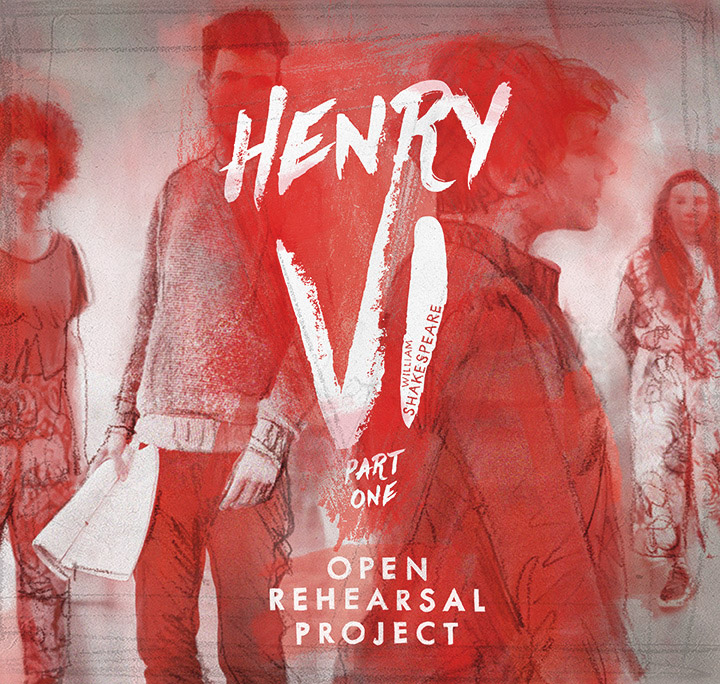

1 Henry VI Open Rehearsal Run-through (RSC) @ online

The three weeks of the RSC 1 Henry VI Open Rehearsal Project – previously discussed on The Bardathon here – culminated on June 23rd with a full rehearsal run through in the Swan rehearsal rooms, as the midsummer light waned through the windows around the room. Running at a stripped-down two hours, this was still a fundamentally whole 1 Henry VI, making the usual cuts (will I ever see Sir John Fastolfe in a stage production?) but retaining a surprising amount of the play’s idiosyncratic flavour, especially the single-scene characters and side jokes that make it such an entertaining and sprawling history. Standing alone (albeit with a ‘To Be Continued . . .’ flashed across the closing moments) and taking place with all of the apparatus of the rehearsal room visible, this was a brilliantly effective production that showcased some fine performances and revealed some of the key structural principles of the play.

The production was well-served by being staged in the round, with actors and crew sat on chairs around the edges of the circular rehearsal room at the top of the Swan theatre. While Janette Dillon has argued for the horizontal structure of this play, signalled so clearly in the first act as the French troops run in and out, the circular setting worked to emphasise a structure based around confrontation and/or key loci. Physical objects such as Henry V’s coffin, the rose bush (a sword rack bedecked with flowers), and an equipment case that served as the Dauphin’s preening platform and a pedestal for Margaret, all took their place at the centre of the circle, with people grouped around them in relation to that object of desire or contention. At other times, individual charismatic characters took this place, especially Jamie Ballard’s Talbot and Lily Nichol’s Joan, in order to hold the attention of others who literally orbited around them. The centrifugal force created around the centre of the circle allowed for a sense of continually shifting allegiances and movements as the fortunes of those embroiled in the wars turned.

The other structural principle revealed by the unique conditions of this as a filmed rehearsal run-through was the importance of soliloquy to this play. Rhodri Huw is a veteran director of the Live from Stratford-upon-Avon productions, and a similar clean aesthetic was followed, privileging the actors and cutting between close-ups for intimate moments and wide shots that captured the whole company. However, this differed from the usual broadcasts in two key respects. The first was that, as a completely in-the-round production that was revealing the apparatus, there was no concern to hide the camera equipment from view, thus allowing for 360-degree coverage and some closer situation of the cast to cameras than usual – in one particularly nice moment, Oliver Johnstone’s Suffolk coyly and physically turned the camera away as he and Mariah Gale’s Margaret prepared to act on their mutual attraction, and Joan’s persuasion of Anna Leong Brophy’s Burgundy back to the French cause was filmed on the balcony with the camera up close and personal with the two, giving this moment an unusual and convincing intimacy.

The absence of an in-person audience, further, meant that this production chose to capitalise on the opportunity for direct-to-camera address for soliloquy, far more so than Live-from-Stratford productions that play in the RST have previously done. Almost every aside involved actors explicitly turning to and developing a relationship with a camera at the side of the rehearsal space, which gave those figures an unusual prominence. For this reason, surprisingly, the character who almost emerged as the lead of 1 Henry VI was Amanda Harris’s Exeter, whose fatalistic, cynical, and troubled end-of-scene asides made the character choric in significance; however, almost everyone got their turn with the camera. The placement of the cameras at the edge of the room created a beautifully judged opposing force to the central gravitational position. Characters such as Talbot and Joan, who had rather less direct address, were the focal points; but the characters who approached the edges of the space to build the relationship with the camera took on a sprecher function, mediating action through their own agenda and viewpoint. And the sheer number of characters vying for this privilege, rather than confusing the action, instead served to foreground the power vacuum at the play’s heart.

Henry VI is notoriously a minor character in this play, and Mark Quartley’s performance exaggerated the king’s boyishness. His throne was not placed central in the circle, but stood off-centre towards the edges, and the king himself cowered in it, curled up and lost within its massive frame, while Gloucester and Winchester’s men burst in to fight one another in front of him, disregarding their monarch’s one attempt to shout them down. Easily swayed and manipulated, this Henry shrunk to the sidelines, only really coming into authority in the stage-managed scene of his re-coronation, where the nobles reorganised themselves to form two parallel lines of obedient subordinates leading up to the throne; but by the end of the scene, as Exeter predicted loss to the camera, Henry was visible in the far distance, out of focus in the depth of field, already becoming peripheral again. And when Henry was absent, the continual movement of the nobles emphasised the fluctuating power dynamics. For the rose garden scene, characters marched to the centre to take their rose but then moved away again, no-one taking the centre for too long. And the throne itself became a source of contested authority: Marty Cruickshank’s Mortimer sat behind the throne, on the edge of the plinth, while talking to Michael Balogun’s York, emphasising the imprisoned man’s proximity to but distance from the throne he claimed. And for his closing soliloquy, Suffolk sat on the front of the same plinth, addressing the camera confidently, not yet assuming the throne itself but only a small step away.

The story of the English nobles is, of course, the one that will go on to dominate Parts 2 and 3, but here, Part 1 was clearly structured around the twin rises and falls of Talbot and Joan. Ballard – one of the finest Hamlets I’ve ever seen, and an actor capable of making even very small roles seem pivotal – isn’t an obvious Talbot. Talbot was a worried-looking, unassuming man, who seemed to be embarrassed by the attention he got, and who seemed almost prone at times to deflation and a sense of defeat. He did his part with rousing the troops who surrounded him, calling out insults against Joan and the Dauphin, but when – as he so often was – left alone, he seemed dejected. This made excellent sense of his encounter with the Countess of Auvergne (Harris), who relished the sound of her own voice came across as an enjoyable upper-class twit with delight in her own ingenuity. Talbot stood, blank-faced, as she walked around him, mocking his appearance, allowing her to acknowledge how he appeared – but when he summoned his men to surround the Countess and show his true power, he quietly and humbly pointed out that his armies are his person. The Countess seemed won over by his approach, curtseying deeply and smiling in her defeat.

But this served in its own turn to show just how vulnerable Talbot was as a man. Earlier, in his first encounter with Joan, he seemed hopelessly outmatched next to the physically strong Joan. The fully staged fight choreography was impressive, and Nichol convincing as more than a match for the men in the English army; at the end of their first encounter, Joan managed to win Talbot’s sword from him, and then threw his back to him with disdain while announcing his defeat; left alone, Talbot seemed lost, a relic from an older age, outclassed by a new generation of fighter. Talbot’s innate sadness was then revisited as a lament for the passing of several generations in the final battle. Standing alone, he called for John Talbot (Gale), who appeared, upright and brave, while the rest of the cast circled around them, twirling their chairs threateningly. The two Talbots then struck out among their enemy, Talbot taking a blow to the head and falling to the floor. Awaking, he called plaintively for John Talbot, only to see Gale cradling John’s jacket. She came and laid it before him, the cameras coming in close on the two as Talbot lamented the loss of his son while staring into the face of the actor who had played him, before quietly dying. This Talbot was never the triumphant leader, but a man who bore the heavy burden of war, and had its horrors fully visited on him in his last moments.

Joan, on the other hand, revelled in her confidence. The French were beautifully realised, with the Dauphin (Jamie Wilkes) repeatedly entering reclining on the equipment case, luxuriating in his own wonderfulness, but still dynamic and physically active as a warrior. The French ran towards and past the camera threateningly in their first foray against the English, then after a single comic beat was left, they ran back again screaming in retreat, all captured in a single unbroken take. In an interesting play on the centre-periphery spatial structure, the centre of power in the room became a place of retreat for them, whereas when they approached the edges they were beaten back. Joan entered the space, however, as if she owned it, smiling benignly at Reignier (Cruickshank) and instantly identifying the Dauphin hiding behind the equipment case. In their fight, which the Dauphin entered with swaggering smugness, she quickly bested him, sending him skidding across the rehearsal room floor. And then she took centre stage, holding her sword out horizontally while the four French nobles gathered around her, moving in a circle as they entered her orbit and fell under her influence.

Nichol’s powerful Joan was confident at all times in war; however, when caught short with the Dauphin during a night attack, the two holding their sheets up to them in embarrassment, she showed her first flashes of insecurity. Joan’s power was a projection when in public, knowing that to influence the world of men she needed to show no weakness. But alone, when she conjured her demons, her anxiety was palpable as she lay a rope on the floor and pleaded desperately with the spirits to aid her. While she spoke, two cast members entered and picked up the rope, looping it around her and then binding her as she called out for the spirits and realised she was left alone – until finally York entered, smiling and vaunting. Later, pulled in as an exhibit on the equipment case, she had lost all control. The case was turned and turned again (just as she had earlier accused Burgundy and all Frenchmen of turning and turning again) to face Warwick (Bridgitta Roy) and York as they shot down all of her pleas for mercy, leaving her without recourse.

Around the edges of Joan and Talbot’s stories there was plenty more going on. Christopher Middleton’s Gloucester and Mark Hadfield’s Winchester were at enmity, with Gloucester presented as entitled and repeatedly outraged while Winchester smiled oily back at his nemesis; Gloucester’s righteous aggression towards his enemy also showed his own weakness, while Winchester waited and snarked. The more ‘noble’ nobles – Exeter, Bedford (Gale) – were central at Henry V’s funeral but quickly displaced, and Exeter’s soliloquies spoke to his sidelining throughout while more corrupt forces took charge. Somerset (Mimî M Khayisa) and Suffolk were set against York and Warwick following the rose-plucking scene, and while this play largely falls into a pattern of the nobles sparring verbally and snarkily at one another, the tensions drawn here set up lots of potential for future instalments while also driving the shifting spatial centres of power. And the retention of the little stories at the edges, such as the one-line English soldier who gets to nick the French nobles’ stuff by shouting ‘A Talbot!’, the watchmen on the balcony at Orleans, and Joan’s plaintive comic father, the production still managed to capture the variety offered by the play on its own terms, rather than just singling out the pieces that would serve the later plays. The whole was given further unity by Paul Englishby’s powerful, eclectic score, which shifted seamlessly between quasi-medieval atmosphere and jarring electric guitars to mark the shifts from politics to romance to war.

In the concluding scenes, Gale’s Margaret of Anjou came to the fore as Suffolk wooed her. This is where the play’s set-up for later plays felt most pronounced, both in content and in the stylistic shift. Johnstone and Gale were entertaining as they played out the metatheatrical scene in which Suffolk ignores Margaret while he soliloquises about his own feelings to the audience, followed by Margaret in turn soliloquising to the audience precisely to give him a taste of his own medicine. This scene in particular required a nuanced modulation in performance, the two both picking and addressing different cameras, which then cut between each of them directly addressing the audience, creating a mirrored set of competing positions, before the two finally turned back to one another (and, in one lovely shot, Suffolk was in the background of Margaret’s direct address, appealing for her attention). For the final scene, Margaret appeared on the equipment case, posing in a visual embodiment of Suffolk’s articulation of her charms for Henry to goggle at. And at the end of Suffolk’s closing soliloquy, he stood up to begin applauding as the camera cut to Henry and Margaret meeting, a rain of confetti falling on them, as the nobles gathered to celebrate a marriage underscored by ominous music and overwritten with the promise ‘To be continued’. It was a wonderful production, and I hope the RSC make good on that promise.

Thank you for this brilliant review! I very much enjoyed watching the production – and the rehearsal process – and you have drawn out so many of the details that made it so successful.

Glad you enjoyed it Simon! Let’s hope we see more in this vein.