July 19, 2018, by Peter Kirwan

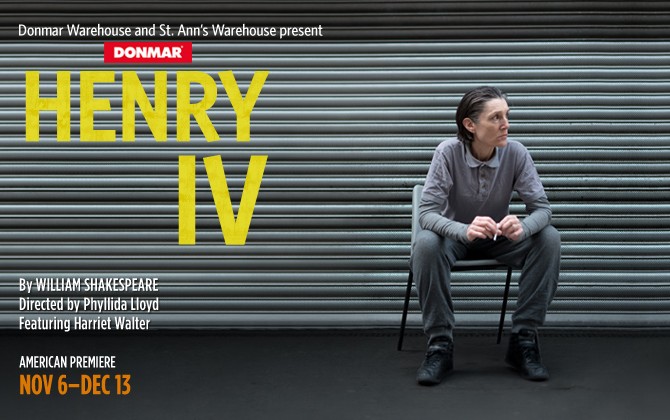

Henry IV (Donmar/Illuminations) @ BBC iPlayer

Following the release of Julius Caesar in cinemas last year, Phyllida Lloyd’s ‘Donmar Trilogy’ is finally available on BBC iPlayer, giving me the chance to belatedly catch up with Henry IV and The Tempest. The films, with live camera direction by Rhodri Huw, offer an extraordinary document of an extraordinary theatrical event, and one can only hope that they will have continuing life after their iPlayer stint ends.

Henry IV, the middle part of the trilogy, is effectively a fast, mostly comedic take on 1 Henry IV followed by a handful of scenes from Part 2 (Lady Percy visiting Northumberland; Hal at Henry’s deathbed; the rejection of Falstaff). Clare Dunne announces the play in her prisoner persona of ‘Rosie’, introducing herself as a heroin addict and repeat offender, and about to get out. In her eyes, Henry IV is about redemption and second chances, and her journey as Hal gives the production its narrative centre. Yet this is also a fundamentally ensemble production, in which every member of the company gets their moment to shine.

The framing device marches the prisoners, still under guard, into an area filled with children’s toys – an easybake oven that is taken over by Mistress Quickly; toy guns wielded by the play’s soldiers; toy furniture and games, which continually provide bathetic undermining of the play’s lofty rhetoric. The prisoners putting on the play are aspiring towards something better while also being constantly reminded of the conditions within which they are working. As with Julius Caesar, the best moments of the production come when the events of the play become more than the framing device can withstand – as most notably as the residents of the Boar’s Head turn on Zainab Hasan’s Hostess to make jokes about her sexual experience. As the comments on the size of her ‘snatch’ and ‘twat’ become more obscene, the prisoner playing the Hostess breaks down, crying that they’d agreed not to do this, and runs offstage. The lights go up as the actors stand around awkwardly (and brilliantly, Lough’s camera also swings freely, as if unsure where to look), and it is Harriet Walter who pulls it back together, ticks off the actors and comforts the upset actor.

Walter, playing ‘Hannah’, plays King Henry IV, and clear wants this to be a more dignified affair than it actually is. Her King is eloquently spoken, authoritative and as dictatorial as Hannah is a director, keeping troops and actors alike under her control. Yet the comic energies of the production threaten this dignity at all times, primarily in the person of Sophie Stanton’s Falstaff, who even interrupts Hal’s big redemption speech to cheer, prompting Walter to break out of character and remind her that this isn’t her scene. Rosie/Hal, for her part, is genuinely torn throughout between the desire to play her part well (especially in front of Hannah/Henry) and the hilarity she feels at Falstaff’s antics – she laughs uncontrollably at Falstaff’s interruption, while aware of Hannah’s disapproval. She is similarly goaded into the insensitive attack on the Hostess by Falstaff, and is the one who leads the apologies at Hannah/Henry’s instruction. The tussle between Henry and Falstaff for Hal’s affections, then, is thus echoed in the prisoners’ loyalties, and at stake is the question of Rosie’s potential to truly change.

The ramping up of the comedy of Part One is key to this, as the simple pleasures of pissing around have especial resonance in a prison environment characterised by boredom. The ‘play extempore’ is a particular triumph in this respect, with the prisoners clearly experienced in dressing up and mimicking one another as a way of passing the time. Falstaff’s impersonation of Henry is a gloriously OTT mockery of Hannah’s (relative) RP accent, and the prisoners split their side as the most authoritarian of them is ridiculed. When they swap roles, Falstaff then gives a brief bit of Riverdance and a gleefully racist send-up of a puckered-lipped, befuddled Irishman as she impersonates the voice of Dunne’s Hal. In this scene, the slow build-up to Hal’s ‘I do. I will.’ becomes a major wrench, as Rosie distances herself briefly from the games of the prison.

The Boar’s Head scenes are characterised by loud music, snorting of coke (the ‘sugar’ brought by Leah Harvey’s Poins) and dancing, all overseen by the Hostess. The all-female cast sends up masculine bravado in the scenes of posturing and insults, and all participants enjoy the freedom that the licence of the play gives them to lay into one another (more than once, Stanton’s Falstaff breaks character to tell them to leave off the fat jokes). The Gadshill sequence is more surreal; the actual robbery is staged by a toy bear being thrown at a remote control car, before Falstaff leaps out at two hilariously stereotypical American tourists. Throughout this sequence and several others, the cast move freely between Shakespeare and contemporary language, particularly improvising insults.

Rosie’s is not the only throughline, though. As with Julius Caesar, Jade Anouka is the major antagonist, playing Hotspur. Throughout the production, Hotspur is seen in training montages – wrestling, fighting a punchbag, performing pull-ups on a bar. The film’s editing adds to the effect by disrupting the ‘as-live’ ethos to juxtapose images that are not clearly sequential. Anouka’s lairy, loud Hotspur is a force of nature, barreling through her scenes with little thought for consequence, especially when mocking Jackie Clune’s more dignified Glendower (whose dignity is somewhat undermined by her deployment of a choir to hum anthems behind her back as she asserts said dignity). In a great comic scene that also shows Anouka’s force, she roars down a payphone at the false friend refusing to join her cause. Anouka is balanced, however, by a similarly imposing Lady Percy in the shape of Sheila Atim, a match in independence and anger for her husband. When Lady Percy visits Northumberland (Carolina Valdés), she even has Hotspur slung over her shoulder, and Lough’s camera beautifully keeps her in the backdrop as she screams for Northumberland to stop the fighting, while Northumberland’s devastated reaction is captured in close-up. It is also Atim who sings the song that closes the meeting of the allied rebels in Wales; Lady Mortimer is cut, but the Percys are given additional time to establish their even partnership.

Driven by Anouka, the build-up to war has the feeling of genuine violence threatening to spill out. Martina Laird is a terrifying Worcester, building Hotspur’s confidence through laughing at his jokes and pushing him to greater taunts of his enemies. Harvey is similarly intimidating as the Douglas, particularly in a bravura martial arts/computer game sequence where she cartwheels among a number of false Henries wearing cut-outs of Harriet Walter’s face and dispatches them to the sound of electronic beeps. The final showdown between Hal and Hotspur is brutal, leaving Hotspur gagging on the floor.

In oscillating between the potential violence and the outbreaks of dangerous comedy, Lloyd’s production paints a picture of the prison as a powder keg, with everyone jostling for their moment to shine. It’s collaborative and competitive at the same time, with very little space for sober reflection. Walter’s scenes as Henry offer quieter pause, especially when commenting on the subjects who are asleep while the other prisoners rest, and while she has far less time commanding the stage in this production than in Henry IV, it seems that the trilogy is setting the stage for a Prospero who is perhaps too fond of being in control.

After the battle at Shrewsbury, the final twenty minutes give a fitting send-off to Hotspur and force Hal to confront her destiny. With ‘Zadok the Priest’ blaring out, Hal announces her reign, only to be interrupted by Falstaff. As Hal berates Falstaff and banishes them, the two take off their costumes and let down their hair, and Hal begins moving up steps towards a barred gate. Falstaff screams for her ‘Don’t go Rosie! You won’t make it on the outside!’ and the prison alarms sound as Falstaff is frogmarched out wihle the rest of the prisoners hit the deck. Dunne isn’t in The Tempest, suggesting that this is indeed the end of ‘Rosie’s time in the prison; though of course, whether or not Rosie does manage to leave behind Falstaff and the behaviours that brought her to the prison remains unknown. But I don’t recall seeing a version of Henry IV where the stakes of leaving Falstaff behind were so high, and Hal’s conflict so visceral. Whether these ideas will be returned to in The Tempest remains to be seen.

Thank you, Peter, as ever, for such a rigorous, informed and thoughtful response. But do note that the (in my view, exceptional) live camera direction is by Rhodri Huw, not Robin Lough. Rhodri was also the screen director for Robert Icke’s Hamlet.

There’s a very interesting set of ideas to explore in relation to the distinctive production of the screen version – and I’m intending to write on that in the future.

Thanks John – genuinely not sure how that happened, so must have seen his name somewhere else as I was typing. Corrected now!