July 10, 2016, by Peter Kirwan

The Alchemist (RSC) @ The Swan Theatre

The RSC’s contribution to the 400th anniversary of Ben Jonson’s 1616 Folio is a Swan production of The Alchemist, occupying the slot that Volpone took last summer. The RSC invested a large, game cast, one of the biggest bands I’ve seen in the Swan for some time, and a production budget that stretched to a suspended crocodile and a genuinely terrifying climactic explosion, and it was great to see Jonson being staged on such a large scale. What resulted was a very funny, if not always fully perfected (to borrow the play’s own terminology) production.

The key issue, for a play that depends so much on its frantic energy, was pace. Director Polly Findlay betrayed a certain amount of anxiety over an audience being able to find its way through the play by employing playwright Stephen Jeffreys to revise the script and write a new prologue. This prologue served to introduce the key cast, show Lovewit leaving London owing to plague fears, and showed the trio of tricksters signing their shared contract. This was, I believe, invaluable; the play’s own exposition (especially if the original prologue wasn’t spoken onstage) can be lost amid the opening argument. However, the compromise is that the play’s extraordinary explosion of initial energy – beginning with a half-line, moving in a crescendo through Face and Subtle trying to dominate the conversation, and climaxing with a line divided five ways between hurled insults – was immediately dampened; Face and Subtle’s anger was bitter and semi-reasoned, rather than full-throat. Slowing down the play to ensure narrative clarity surely has to diminish something of the play’s combustible, seat-of-their-pants interactions, and when the production got up to speed it was excellent; I just wish this had happened more.

The mise-en-scene was a glorious mish-mash of kitsch and period (1610) setting. A table dressed with skull and fruit resembled a still-life by one of the Dutch masters, while the suspended crocodile (revealed to contain the con-artists’ secret stash, and looking for all the world like a piñata; I thoroughly expected it to explode in a shower of golden coins) and a magical prop of an upraised hand (that Face high-fived) introduced an element of tackiness. The band, in an extraordinary opening medley, combined orchestral music with snatches of Bond, The A-Team and the theme from The Italian Job. The overall effect was of a mutable, responsive space, located at a particular moment but able to be whatever it needed to be for its customers. Indeed, the best sequences came as the trio frantically rushed about, scrambling into different costumes to receive unexpected visitors.

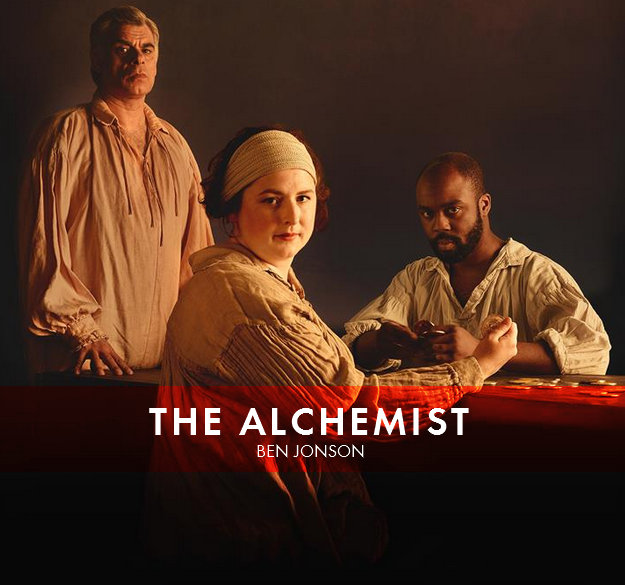

The central trio worked well together throughout. Siobhan McSweeney was a fabulously reactive presence – while the role has far fewer lines than Face or Subtle, she took on an important visual role through gesture, hissed whispers and threats of violence. Dol was the most physically powerful of the trio, and the quickest to move to physical interaction: when gulling the blindfolded Dapper, she took charge of dictating the kicks, pinches and slaps that finally revealed the hidden riches about his person (whereas Ken Nwosu’s Face seemed genuinely more willing to believe the young man). Dol was hoisted into the air to swing freely as the Fairy Queen, and switched quickly between smiling and casting glitter on her ‘nephew’ and shaking her fist at Face, whose carelessness with the rope left her swinging. It was in Dol’s performance that the stress of the improvisation was best realised, which was key to keeping the stakes of the long con at the fore.

Face and Subtle (Mark Lockyer) were less individualised than Dol, which is perhaps inherent to their performances; the play shows far more of Dol in her own person relative to the parts she plays, whereas Face in particular disappears so far into his different performances that it is more of a challenge to find a core for the character. Nwosu’s triumph was in his busy, Mosca-like bustling about and under the stage, keeping the various plates spinning. Face worked twice as hard as anyone else, and was especially amusing in the goggles and cloak get-up that he adopted as ‘Lungs’. Subtle, meanwhile, was a somewhat down-and-out conjuror even when in his various disguises; he spoke with gravity, but gave a performance of a weary (or wearied) man, worked to the bone by his various projects. As a double-act, the two created an enthusiastic/reluctant dynamic that worked perfectly for the gullings, placing the mark physically alongside Face (always in a position where Face could express his true sentiments to Subtle without the mark seeing him) and facing Subtle. Subtle’s weariness gave him the power of fascination, as he finally acceded to the requests of the applicants.

The various cons were all individually entertaining, but perhaps a little flattened by the choice to place the unseen laboratory under the stage, which vastly decreased the speed at which Subtle and others could move in and out of that space. Of all the tricks, that played on the hapless Dapper (Joshua McCord) was the most spectacular, with Dol swinging above him; the rest depended more on the individual interactions with a group of nicely differentiated gulls.

The quietest of the gulls was Abel Drugger (Richard Leeming), played here as a simple, kindly man who brought flowers for Dame Pliant and constantly offered his fine tobacco to the other characters. The production found a certain amount of complexity in presenting him so sympathetically, showing up the crueller aspect of the tricksters (apparent also as Kastril casually mentioned his annual worth, leading Face and Subtle to both visibly catch their breath). At the opposite end of the spectrum were the brilliantly obsequious Ananias (John Cummins) and Tribulation (Timothy Speyer). In Ananias’s early appearances, he kept an even temper, repeating his requests patiently and slowly while smiling beatifically; as the play went on, his anger came to the surface and he screamed defiance at Face while whipping his belt cord into a damaging-looking flail. Tribulation was even more sickly in his fawning over Subtle, and the two’s hypocrisy as they agreed that they could cast money, if not counterfeit, placed them firmly on the murky side of the play’s moral line.

Sir Epicure Mammon was played by Ian Redford as an older and ailing man, breathless with his own vaunting but unable to perform. When he had Dol (in disguise as a mad noblewoman) on her back on the floor, he lowered himself onto her, but then was left rocking in fixed position on the floor until Face was able to help him back up. There was a smattering of spontaneous applause for the first of his epic monologues, but this older, impotent Mammon didn’t have as much of a presence as I’ve come to expect from the character. Instead, it was Tom McCall’s Kastril who stole the show with a scenery-chomping performance. His screeching screams of ‘You lie!’ and his flailing around when he tried to be threatening made him an unpredictable presence. The finest sequence in the production saw Kastril lead a three-pronged charge against Surly (Tim Samuels), roaring his ‘polite’ insults in the bemused man’s face while Ananias attacked Surly from the right with his flail and Drugger flapped his bunch of flowers at him.

While the individual vignettes all worked effectively, the production came apart a little towards the end. The final breaking of the partnership was both surprisingly slow, taking time to establish the anger of the break as Subtle and Dol left the stage, and also far too quick, feeling perfunctory and anticlimactic. The production clearly cared about the breaking of this bond, but shuffled Dol and Subtle off before it was entirely clear that that was what was happening. And the return of Lovewit (Hywel Morgan) was also underplayed; for a long time after his return he cowered behind Face and, even once reasserting himself, seemed surprisingly hands-off (the one exception being him lamping the smiling Drugger). The suggestion here, however, was that Lovewit’s appropriation of the tricksters’ plot was part of a more sinister power politics. Surrounded by three heavy-handed policemen, Lovewit’s victory seemed to be that of the 1%, re-establishing traditional hierarchies and drumming everyone else out of his house with hired violence, and a tip to his faithful lackey. I’m not entirely sure his return quite earned this reading, particularly amid the general jollity, but it was a pleasing gesture towards topicality.

The epilogue, spoken by Face, finally brought it all back to the theatre. Nowsu took off his costume onstage, revealing a Ramones t-shirt and jeans beneath, and while doing so he counted up the audience and the price of their seats. The final trick, the long con, was that played on the audience, it seemed – and as he took off his trickster’s disguise, he made clear how much money he and his colleagues had scammed out of the audience. The analogy doesn’t quite work – after all, we got what we paid for – but it allowed for a nice touch as the house lights went up and the rest of the cast re-entered in their own clothes to take a bow in shared acknowledgement of the trickery of the theatre.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply