October 23, 2015, by Peter Kirwan

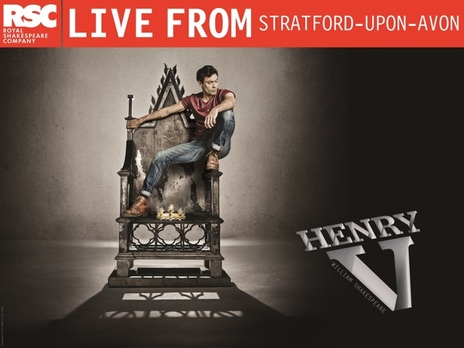

Henry V (RSC/Live from Stratford-upon-Avon) @ The Broadway, Nottingham

Gregory Doran’s jaunt through the second tetralogy has come to its climax with this, a Henry V lauded by The Telegraph as ‘the production this country needs’. Following some discussions on Twitter, I remain unconvinced by what exactly this country might ‘need’ from Henry V. Leaders born into privilege who disguise their true purposes and manipulate their suffering subjects into making punishable statements? Spin doctors who ret-con heinous acts of war as justifiable responses to ‘provocations’ that actually happened after those acts? The strategic deployment of Scottish and Irish subjects when needed for a ‘national’ purpose, while at the same time mocking those subjects for their regional difference? A ‘band of brothers’ that then only remembers the names of the high-born dead? Dubious rationales for going into a war in the first place? And all excused in the name of religion, hereditary privilege and an anachronistic patriotic identity? If this is the play we need now, we need it as critique of Blairite, Cameronian and Farageish attitudes to God, country, foreign policy and class. Somehow I doubt this is what prompted Dominic Cavendish to kneel before the Royal Shakespeare Theatre and kiss English soil.

I’m being deliberately cynical in my skewed reading of the play, of course I am. One can go back and forth over the politics and allegiances of this play; what I choose to resist are the aligned notions that (a) this play’s default position is patriotic and (b) that, if it is, we should be celebrating its particular version of patriotism. And Cavendish’s flush of patriotic fervour isn’t, I think, what this production obviously sought. In fact, to continue the analogy, the production came with its own built-in Jeremy Corbyn in the shape of everyone’s other favourite granddad, Oliver Ford-Davies as a cardigan-wearing Chorus. While the Chorus did not offer overt critique, what he did do was puncture the bubble repeatedly. The play began with the Chorus wandering onstage and picking up the crown that sat on a throne centrestage, only for Alex Hassell – just finishing putting on his costume and carrying a bottle of water – to walk on stage, pluck the crown from him, shake his head and leave. Later, the Chorus irritated actors with his false starts and his apologies for their rudeness. But it was also left to the Chorus to conclude, quietly, with the promise that all this bloodshed would ultimately prove futile.

Further, several of the production’s best moments featured challenges – explicit or covert – to Henry’s moral authority. Henry’s instruction to kill the French prisoners was followed by Erpingham and others pulling off a troupe of men with sacks over their heads, and Antony Byrne’s Pistol was left alone onstage with the cowering Monsieur le Fer (Daniel Abbott). A distraught Pistol pulled out his dagger and then hauled out the screaming Frenchman, who later appeared above, opposite Martin Bassindale’s dead and bloodied Boy, during the requiem for the dead, ensuring that Henry’s decision was not skimmed over. More brilliantly, and causing quite a shock in the cinema where I saw the screening, Simon Yadoo’s Michael Williams begged Henry for pardon following the exposure of their feud, before then punching him in the face. I’ve never seen this decision before and it showed Williams to be one of extraordinary integrity and courage, qualities that it took Henry a punch in the face to recognise. He embraced his relieved subject and left Fluellen bemused.

The pre-show materials before this screening were some of the most intrusive and unwelcome I’ve yet seen in a Live from Stratford-upon-Avon event, perhaps because they so closely aped the less desirable aspects of the play itself. Interviews with Doran, Hassell and Ford-Davies (the latter two recorded) worked hard to impose an interpretive framework on what followed, with Hassell in particular responsible for outlining his understanding of the play’s stance on war (not jingoistic but not anti-war – instead about the experience of war). The interviews were peppered with so much footage of the production itself that I seriously considered, for a moment, just leaving (admittedly, I have a lot of work on just now). This is my problem with both Henry V and with Live from Stratford – I resent being told how to interpret what I’m seeing. With that said, Ford-Davies’s important insight was to highlight how often the Chorus’s words jar against what is seen, and I wish they had pushed further to set him up as an oppositional figure.

Hassell noted in the interview that he couldn’t imagine playing Henry without having first played Hal, and there was a sense of a long journey paying off. Although Mistress Quickly had been recast for this production (Sarah Parks replacing Paola Dionisotti), the production worked well to build on the goodwill for Joshua Richards’s Bardolph and Byrne’s Pistol in particular. Richards was excellent as Bardolph, a gruff and relatively stable figure representing an earthy consistency in the troops; it was harder to imagine this Bardolph as a thief. Pistol, too, was more sympathetic here – while still retaining a certain amount of fiery temper, particularly in his early wrestling with Nym, he was also the one to begin singing war songs on the march, and a plaintive pleader for Bardolph as well as feeling the impact of having to kill le Fer. Doran’s skill as a director is, I think, to individualise characters who can in other hands become one-note, and while the comic scenes fulfilled their broader function in shadowing the main plot in a more questionable light, they were more important in showing the visceral effects of conflict on characters developed over several plays.

Henry’s increasing separation from his roots forced some changes to Hassell from his work in the Henry IV plays. With his legs and arms spread to enable him to take up slightly more stage space, Henry seemed to still be establishing himself as king, and was much more comfortable as soldier, whether clapping his soldiers on the back or leading the charge into Harfleur. His default mode was a privileged sincerity and (helped by similarities in the voice to Hugh Laurie) I couldn’t help but think that he came across as a considerably cannier George from Blackadder Goes Forth. Or perhaps less offensively, to Prince Harry, whose joshing camaraderie with his comrades was on the news just yesterday. Henry’s easy confidence meant that he defaulted towards attitudes similar to that he struck with Poins in the earlier plays, always shifting to standing alongside his men rather than above them. His confidence allowed him to drop into any conversation easily, yet avoided becoming arrogance through his affability and generosity – an officer toff who nonetheless got his hands dirty and got to know his men. It was, therefore, not hard to see why his men loved him. While the big set pieces – ‘Once more unto the breach’, ‘We few’ etc – were handled well, Hassell was even more convincing in the subtle details round the edges, in the glances and minor contacts that made clear his belief in giving every soldier around him a sense of personal connection.

The same privileged confidence displayed in the wooing scene could have been offensively one-sided as he assumed his ‘demands’ in Jennifer Kirby’s Katherine. Happily, Katherine was lively and fun, happy to play coy and woo her prince in turn. Supported by Leigh Quinn’s Alice and Evelyn Miller’s Lady-in-Waiting, Katherine was a formidable figure. The French-speaking scene made the most of the double entendres and presented Katherine as somewhat spoiled and demanding (insisting her maid applaud her efforts at English) but deeply loving of her companions. The three made a fine team against Henry, with Alice pronouncing ‘de tongues of de mans is be full of deceits’ as ‘de shits’ in a deliberately confrontational tone. Katherine shifted throughout the scene from some distress at her position to joyful laughter at Henry’s stumbling, while Henry himself enjoyed the fish-out-of-water moments, poking fun at himself even as he moved toward increasing sincerity. It was, eventually, she who grabbed his face for a passionate kiss. The appearance of Jane Lapotaire as Queen Isobel for the final scene jarred a little, her dignity and eloquence seeming to com efrom a different play, but reinforced the sense of strong women overseeing the transition at the play’s end.

The bare stage returned to the use of projections seen in Richard II for the evocation of deep environments such as cathedrals. A glow under the platform stage lent colour to the battle scenes, but there was very little conflict onstage. Henry was alone for ‘Once more unto the breach’, and the excursions were very rarely seen; normally the scene opened after battle had desisted. The bare stage and three-dimensional blocking allowed for excellent camerawork – the start of 1.2 saw the camera positioned behind the Archbishop’s head, letting the audience see Henry for the first time from his point of view, and the cameras frequently captured the audience from a high angle, filling the backdrop behind Henry or Pistol. Pleasingly it felt like there was a predominance of broader shots that captured the blocking and overall look of the stage, though this also heightened the relative emptiness of that stage. The Chorus’s introduction of theatrical machinery (and an exposed section of bare wall and props upstage at the start and end) made the apology for this sparseness part of the production’s design, and the camera still allowed Henry to fill the picture as needed.

There was good work elsewhere. The scene between the four captains fell into crude stereotypes for its comedy – Yadoo was incomprehensible but very funny as Jamy, leaving Fluellen and MacMorris scratching their heads and floundering to reply to his statements; Andrew Westfield’s MacMorris fumbled with grenades and shook them against his ear to hear if they were likely to blow up, which is at least the second time I’ve seen an Irish explosives expert as a ‘funny’ role on the RSC stage. Richards played Fluellen with brisk efficiency, the mode for many of the officers (Sean Chapman’s Exeter even looked like a 1940s Air Force general), and he gave a self-deprecating performance throughout, embarrassing himself by repeatedly interrupting Henry’s attempts to pray on the battlefield, and reacting with quiet surprise to the realisation that Pistol was a fraud. I felt, too, that the conspirators’ scene worked very well, the three men going through a fine and balanced transition from huddled preparation to fawning compliments to humiliation, anger and debasement. However, the inclusion of a thwarted moment where Cambridge actually lunged with a dagger at Henry’s back only to miss his moment seemed far too crass – there was no sense of how or why Henry could get into a position where this was possible, given what he already knew.

There was a lot to enjoy in this production, which worked hard to give every character their own moment and explore the complexities of the war experience. Yet its focus on individual experience (war affects everyone) seemed to allow it to sidestep more pressing political questions about responsibility, compromise, ethics and suffering. The production’s strong emphasis on Hal’s deference to God (ending many scenes looking up to the heavens) seemed to me to be a statement about the production’s whole approach – we didn’t create this situation, we’re just seeing what it does to the people who are there, which is what I also disliked about the BBC Hollow Crown production. What this country needs, I suggest in response to Cavendish, is a production that moves beyond asking how our soldiers are dealing with war to challenging what we’re doing there in the first place.

The Battle of Agincourt felt a little peripheral to this staging; I think too much humour before and after the bloodshed (the whole ‘Shog Off!’ thing was pure pantomime) gave the sense that the soldiers had rather won a tricky game of cricket than an impossible battle. The highlight of the production was the closing wooing of Katherine, which was indeed wonderful. Henry’s nasty threats to the walls of Harfleur were redirected by Hassell into the audience itself; a canny move, inviting us to imagine ourselves on the other side of ‘the famous victories’. I must confess that I, like you, don’t care for this play particularly. Hope to make the Henry IV cycle in London.

‘a tricky game of cricket’ – rather! Thanks Michael, and hope you make it to the Henry IV, and also the Richard II if you didn’t catch it first time around!