August 27, 2015, by Peter Kirwan

Othello (RSC/Live from Stratford) @ The Broadway, Nottingham

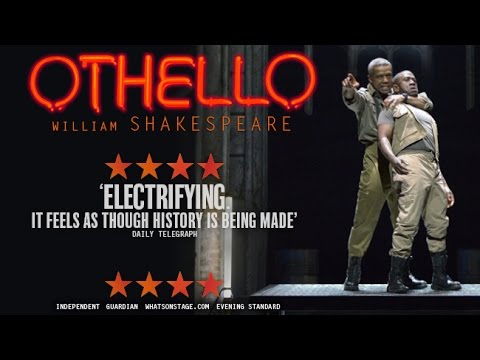

With the exception of the German production that played for four nights during the Complete Works Festival, it’s been well over a decade since Othello was last on the main stage at the RSC. Of all the plays deemed controversial, from The Taming of the Shrew to The Merchant of Venice, Othello is the one the company seems most wary of touching, perhaps owing at least in part to the company’s own well-documented troubles with casting practices. Yet perhaps this absence is a blessing in disguise, if the company – rather than churning out another derivative production of a curriculum favourite every two years, as is often the fate of Twelfth Night or A Midsummer Night’s Dream – has waited until it had something to say about the play. Iqbal Khan’s production was timely, idea-packed, and wonderful.

Tempting Hugh Quarshie to finally undertake a role that he has vocally been reluctant to play for many years was perhaps the clearest sign that this production had found some way to grapple with the play’s legacy concerning race. The casting of Lucian Msamati as Iago, disrupting the usual white/black coding of its central roles, may have struck some as a gimmick, but the strength of these two actors was in their complex negotiation of a relationship that cannot be so easily defined; and, as such, Quarshie and Msamati were part of the production’s opening-up of the play’s questions (much as Munchner Kammerspiele’s casting of a white and much older actor as Othello drew attention instead to the play’s discourse around age). For Khan, this was not a production about a society against one man, but a society divided against itself.

This production, in fact, confronted racial politics head-on in a way I haven’t seen many Othellos do, but here the ‘racist’ figure was Cassio. Jacob Fortune-Lloyd assumed privilege explicitly with Iago’s wife, kissing Ayesha Dharker full on the lips upon his arrival in Cyprus and announcing his right. Later, in a vibrant and visceral drinking scene, Cassio let his guard slip as he began treating the various black soldiers with boorish disdain. Iago sang a melancholy, heartfelt song in a foreign language (I’d be delighted if anyone can enlighten me which) to which everyone listened in silent appreciation until a laughing Cassio interrupted to start screaming the lyrics to ‘Mr Boombastic’. A rap battle was then initiated between Cassio and David Ajao’s Montano, where Montano responded to Cassio’s racial insults about a black governor with his own warnings about what happens when a white lieutenant gets to hold a gun. The topical resonance was electric, the play speaking to a 2015 in which insidious institutional racism is headline news.

Despite modern touches such as this, the production felt out of time, from the fabulous and elaborate robes of Nadia Albina’s Duke and the rickety rowing boat in which Iago and Roderigo began the play to the rudimentary mobile communications equipment that Othello and Iago attempted to tune while Iago worked on Othello’s jealousy. The most modern performance, perhaps, was that of Joanna Vanderham as a complex Desdemona. Not only did she, thankfully, attempt to run from Othello as well as struggling at the end, but she showed her displeasure from the moment Othello began abusing her. Actor and director worked hard to find those moments of the text where lines often delivered with deference could be bitter and accusatory (‘I will not stay to offend you’), which gave a more powerful arc to Desdemona’s gradual realisation of the danger she was in.

The highlight was Msamati, whose unexpected distinction was a form of OCD. This Iago could not bear human contact, and wiped himself vigorously ‘clean’ with a scarf every time this became a necessity. This debilitating condition prevented him forming close relationships, as was most evident as Emilia gave him the handkerchief and kissed him, hopefully, full on the lips. The camera perfectly captured here Msamati’s inability to kiss her back, and she withdrew with tears in her eyes. As she left, ignoring Iago’s feeble gestures, Iago desperately rubbed his knees, straightened chairs and slammed a trunk lid repeatedly, his repressed disgust surfacing in a roar. Repeated instances saw him horrifically uncomfortable as a crying Desdemona turned to him for a supportive embrace, and he was forced to dry her eyes with the backs of his hands, as well as don gloves before the attack on Cassio. Fittingly, and indicative of his state of mind, he used his ever-present scarf as a torniquet for Cassio, abandoning it before the final scene.

Iago’s physical distancing of himself from the others around him was pieced out in the direction, which at times saw him deliver soliloquies while the rest of the company moved in slow motion about him. The physical camaraderie of the soldiers and locals (these scenes well drawn, and the gender mix in both groups making a welcome change from the all-male drinking bouts of other productions) was premised on trust and intimacy; Iago pulled away from this whenever he saw it. Even Othello and Desdemona joined in the early stages of the revels, dancing together for their troops, and Cassio was at his most brash as he kissed Bianca passionately in front of the soldiers. Iago, by contrast, worked in straight lines and angles, his salutes and rigid stance to attention crying for discipline and implying that his perceived ‘honesty’ was part and parcel of his fastidiousness.

The audible quotation marks Iago placed around ‘The Moor’ every time he used the phrase made clear that this was a mocking term repeated from elsewhere; either used by Iago to indicate his own bitterness that Othello was ‘the’ Moor, or else critiquing a society which had found only one way to distinguish its general. Quarshie was a severe, violent man, civilised but quick to anger (and I particularly appreciated the kick by Tim Samuels’s Lodovico that knocked Othello’s body from a kneeling position to a sprawl, undercutting what seemed to be a completely delusional self-delivered eulogy). Quarshie was powerful and brutal, giving Desdemona no opportunity to defend herself and throttling her with his bare hands, but also pulling Emilia around by her arm and subjecting Iago in particular to a brutal torture sequence.

The torture needs discussion. I applaud any production that seeks to remind Western audiences of the unpleasant underbelly of its colonial projects and foreign engagements, and the production set up a superbly ominous tone by having a dumb show of Othello’s soldiers torturing a man with drills and hammers, and then immediately placing a domestic scene of Othello and Desdemona in the same location, with Desdemona idly and unknowingly handling the instruments of violence while Othello carefully took them away from her. But torture is also a provocative thing to show onstage, and crucially there was no internal rationale for its deployment here – the wars are over, and other than this one torture of an unseen man (who was he?) there was no indication or exploration of ongoing military actions in Cyprus. Instead, torture was used as an aesthetic device for shock, establishing this simply as something Othello approves of in order to stage a violent second encounter between Othello and Iago after the discovery of the handkerchief, in which Othello strapped Iago to a chair, suffocated him with a plastic bag over his head, drove nails(?) into his neck (drawing copious blood) and held a hammer to the back of his head. The sudden deployment of graphic violence (captured in close-up by the camera in a scene I frankly would have given more than the production’s ’12’ certificate to*) felt crass, blowing up the subtle work hitherto done by Quarshie and Msamati into a melodramatic crisis. The implication of Othello’s violent potential was justified and effective; the gruesome realisation too much. In any production of Othello, I feel, it should be Othello’s murder of Desdemona that is the apotheosis of his violence, otherwise you risk diminishing that moment.

And in fact, the production’s final scene was curiously flat. It looked beautiful, Desdemona sleeping on a mat at extreme downstage while the Cypriot decorations on the floor and walls stretched far behind her, but the staging seemed confused. Emilia, elsewhere excellent, milked her ‘I’m going to speak now’ section interminably while Iago stood, unrestrained, behind her not intervening; everyone stood around impotent while Othello prepared his own death; and Iago’s final barks of laughter/sobs were oddly sidelined (though this might have been an effect of the camera). Having made so much of the Iago-Othello relationship throughout, these two were separated; and, apart from Othello’s ignominious final posture, the finale was a disappointing anticlimax.

This is not to detract from the otherwise overall excellence of the production, about which there is too much to say to piece out here. Brian Protheroe in particular was a superb Brabantio, dressed in the same velvet as Othello and full of heartbreaking emotion, torn between anger, sorrow, disgust and betrayal. Ciaran Bagnall’s design complemented Fotini Dimou’s beautiful costumes perfectly, the combination of the visual elements capturing the shimmering water that lay under a grille on the stage while still providing a flexible space for a dizzying variety of scenes (designers of recent RSC productions should take note). And the bass-heavy score created a sonorous, heavy atmosphere that built steadily towards the play’s inevitable conclusions. While misjudged in places, Othello’s return to the main stage found purchase on the play, using its contemporary sensibilities to show that the play’s dynamics are much more complex than often represented, and giving the extraordinary Msamati the role of his life.

* Out of curiosity, I don’t know if the production DOES have a certificate, but ’12’ is advertised for all RSC productions on my cinema’s website. I assume the BBFC doesn’t actually award certificates for live broadcasts, but it’s an interesting question.

** A later addition – this live screening was beautifully filmed. From the opening establishing shot to the side angles that gave the Venetian canals their depth, from the close-ups on the significant embraces to the perspective angles on the bed, this was the moment where Live from Stratford really nailed how to film that thrust stage. Hurrah!

Many thanks, Peter. The 12 certificate is set in advance for all live broadcasts, and then it may be reviewed for encores and repeats. Preparing for the broadcast, and thinking about the two torture scenes, we were acutely conscious of our responsibility both towards the intentions of the production and the audiences who would view it – and indeed we took advice from the BBFC. We hope we got the balance right.

Thanks John, that’s fascinating to know. I think the politics of ratings are beyond my ken, though for my money I think the close-ups of the torture sequences pushed the 12 rating to its limits. It was interesting talking to a friend who saw it in the theatre last week and who saw little of the blood or metal; I’d be fascinated to hear your thoughts on if and how far the camera makes more graphic something that the scale of a theatre leaves far more suggestive…