April 25, 2015, by Peter Kirwan

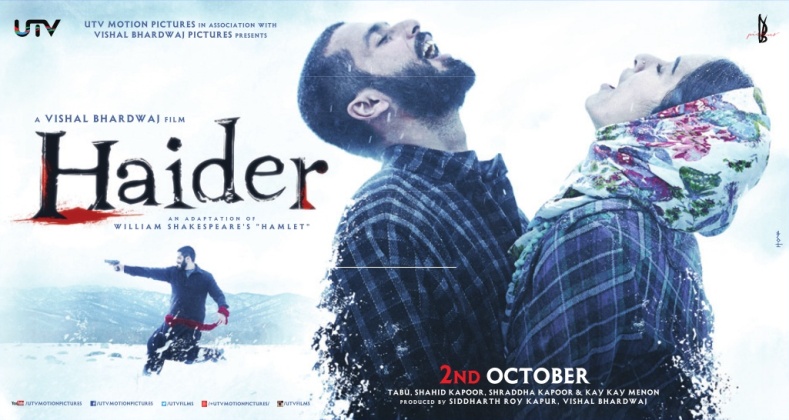

Haider (dir. Vishal Bhardwaj) @ Warwick Arts Centre Cinema

The third of Vishal Bhardwaj’s trilogy of Indian Shakespeare adaptations, following Maqbool and the excellent Omkara, is his most ambitious yet, and possibly the most aggressively political Shakespeare film I have ever seen. The film, set at the height of troubles in Kashmir in 1995, has been the subject of a huge amount of controversy, from its clear bias against the Indian military (mitigated somewhat by post-film praise for the army’s more recent humanitarian endeavours) and extreme violence to the exploitation of sacred sites in Kashmir, where the entire of principal photography was completed without incident. Yet the finished film has also drawn huge audiences in India, testament to Bhardwaj’s epic, heartfelt, intelligent achievement here.

As with Omkara, Bhardwaj adapts Hamlet intelligently to speed up certain parts of the action while also pulling much of the play’s backstory into the present narrative. The film begins with the ‘disappearance’ of Haider’s doctor father Hilal (Narendra Jha)and the destruction of the family home following the discovery that he is treating and harbouring a Pakistani-trained militia leader. The entire first half of the film traces Haider’s (Shahid Kapoor) quest to discover the whereabouts of his father, joining the ‘half-widows’ of other victims of an oppressive police state, before the appearance of a mysterious figure called ‘Roohdaar’, ‘Ghost’(Irrfan Khan) just before the interval, who turns out to be the escaped cellmate of Haider’s father and the only one who can confirm the father’s death, initiates the main action of Hamlet in the second half.

Bhardwaj is thus able to construct different kinds of narrative. It is not until halfway through the film that there is any indication that the Claudius figure, Khurram (Kay Kay Menon) had anything to do with his brother’s disappearance, and as he runs in elections on a platform based on finding his brother and other disappeared men, the early tensions between Haider and Khurram are based around Haider’s deeply disturbed feelings towards his mother and her apparent happiness spending time with Khurram. The film reveals its secrets gradually, and Haider’s mother Ghazala (Tabu) becomes ever more important, first as we discover that she spent her time starving herself, running away and pretending suicide in order to manipulate her son and husband into doing her bidding, and then later as we find out that, despite this, she had no idea that Khurram was an informer. Khurram is a lawyer who represents those with missing relatives, and the film cleverly wrongfoots even an experienced audience by offering the possibility that he is a genuinely good man.

The women of this film have enormously expanded roles from the source text. Far from being passive, the Ophelia figure, Arshia (Shraddha Kapoor) appears early on to rescue Haider from a checkpoint when he returns from university in India (he’s a PhD student of English-language literature) and fulfils the Horatio role for most of the play. They are in a relationship which, at the crucial halfway stage after Haider has learned the truth about his father’s death, brings him genuine happiness in an extended pop-video sequence of lolling naked before an open fire in a cabin in a beautiful snowy woodland area. Her father, the chief of police, abuses her trust to get information from her about his plans, leading to a public denouncement of her treachery, after which she is found singing by Ghazala and later kills herself, seen lying in bed wrapped in red ribbon and cradling a pistol. The pathos attached to Arshia here is extended through a complex and full exploration of her character as Haider’s constant companion with independent agency.

Haider’s relationship with Ghazala is even more charged. The two’s physical proximity constantly evokes a Freudian situation, the desperately unstable mother and the scared little boy needing each other more than they need anyone else. Haider’s discomfort when he sees his mother laughing is followed by open accusation of his mother on several occasions, and the closet scene (which takes place in the bombed-out ruins of their family home) is touchingly intimate. Brilliantly, a situation is contrived in which Haider lies drugged in bed before being shipped to an asylum while his mother lies sleeping holding his hand. We then see Haider’s father walking through the house, approaching and entering the room to whisper to his son, but it is Ghazala who wakes to see him, shocked to find her husband stooping before her; before then Haider wakes up. The complexity of a situation in which Haider dreams not only of Hilal having an independent existence of himself around the house, but in which he imagines a situation where his mother rather than he himself is the one to encounter the Ghost, speaks volumes about the mental state of the young man.

Upon his return from India, and his rejection of his mother and uncle when he sees them laughing together, Haider stays with the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern of the film, two hapless video-store owners both called Salman who want to be spies. They contribute actively to the persecution of Haider, knocking him out when he tries to flee the wedding of his mother and uncle, and then driving him out into the wilds to kill him. The film betrays its longing to be a full-on action film as the ambulance skids off the road and Haider pursues the Salmans to a bloody death, bludgeoning them with rocks. The film’s violence is graphic throughout, particularly in the extending flashback story by the Ghost of the torture of prisoners in the Indian milita’s camps, and in the final showdown – of which more in a moment.

The film’s politics are far from impartial. The representative of the Indian military speaks almost entirely in English, clearly positioning them as the oppressors of Kashmir. When Haider performs his ‘madness’, he does so in the form of a political rally, crying out for freedom and bringing the people together. His encounter with the Ghost’s militia cell, and murder of the Salmans, radicalises him, and he ‘crosses the border’ to Pakistan to train for the militia. But the politics are also personal. In the film’s main setpiece item number, the ‘Mousetrap’ substitute (but here a wedding entertainment for Khurram and Ghazala), Haider leads a troupe of dancers and puppeteers at the foot of a temple in a full-scale recreation of his uncle’s treachery in arranging his father’s death. Haider finishes his critique by bouncing onstage and there is no delay – Khurram looks him in the face and tells Haider where he has got his story from. The speed and immediacy of events, preventing Haider from even having the chance to delay, keeps the film’s pace up but also gives Haider genuine dilemmas to solve. This is a film far more about escaping from situations than about deciding whether to get into them.

This all sets up an extraordinary climax in which Haider returns to a graveyard where three old men sing and dance around the graves they dig. Holing up with them, we learn that they are a clandestine militia cell. But Haider’s resolve to take part in the cell’s activities is disrupted by the arrival of Arshia’s burial, to which Haider cannot prevent himself being drawn. Liyaqat, the Laertes figure – a brief but powerful presence in this version of the story – has no time for anything as genteel as a duel, and the two get into an immediate life-or-death struggle with spaces, ending with Liyaqat dying as his head strikes a rock in the ground. But Haider then has to retreat with Arshia’s body to the gravediggers’ shack, setting up the film’s most obvious Wild West homage.

With Haider as Tony Montana and the gravediggers as The Wild Bunch (with direct visual quotations from those films), Haider ends with an explosive siege. Khurram and his troops arrive with grenades and rocket launchers while the rebels hold them off with machine guns, and blood is spilled in spectacular style on both sides. Fascinatingly, this militarised, quick-acting version of Haider feels organic, as if the parody of Last Action Hero had been set up in all seriousness as an inevitable response to a military situation. Yet the film’s most extraordinary moment comes as Ghazala enters the house to persuade her son to surrender. Failing, but reconnecting with him, she emerges from the house to reveal that she has met with Roohdar and been rigged with a vest of grenades, which she detonates. Khurram is left crawling, screaming away from the wreckage with his legs torn off below the knees (surely deliberately echoing Anakin Skywalker’s fate in Star Wars Episode III!). He pleads for Haider to put him out of his misery but Haider, hearing in his mind his mother’s warning that revenge brings no peace, staggers away instead, disappearing from the frame.

Haider is surely Bhardwaj’s masterpiece. It is at once a rumination on how Hamlet would look in a contemporary situation without the same reasons for delay, and a passionate plea for peace and reconciliation, but also justice, in Kashmir. It daringly juggles a range of complex and nuanced performances, including the breathtaking transformation of Haider himself in Kapoor’s performance from young child through sexy student, bedraggled protester and haggard madman to steely militant, without ever losing the central, inquisitive, damaged thread to the character. All of its characters are treated with respect, and the landscape of Kashmir – its snowy mountains and endless lakes in particular – can never have looked so beautiful. This is destined to be a class in Hamlet’s performance history.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply