February 23, 2014, by Peter Kirwan

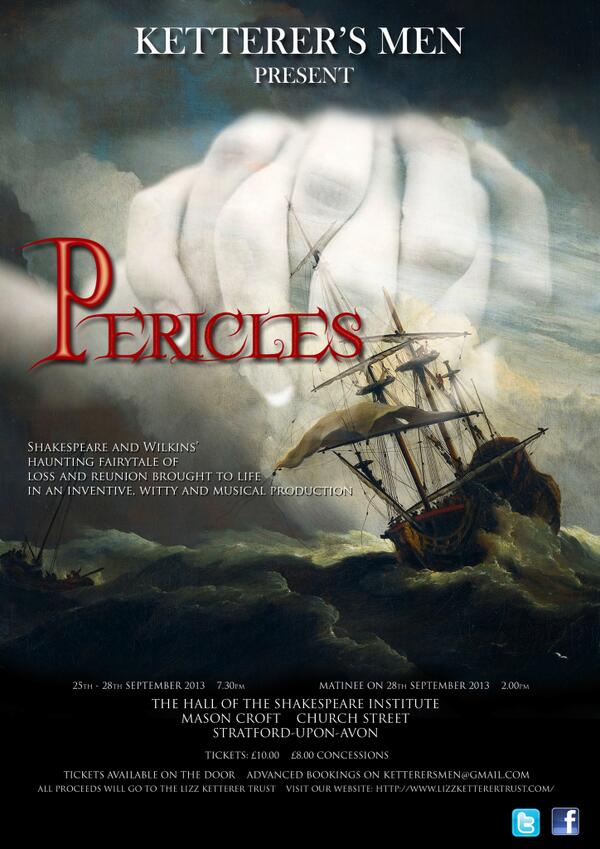

Pericles (Ketterer’s Men) @ The Shakespeare Institute

For those of us who knew Lizz Ketterer, even partly or briefly, she remains a very present absence three years after her passing. The Trust set up in her memory raises funds to allow one promising young early modernist each year the opportunity to attend the RSC’s summer school; the bench in the garden of the Shakespeare Institute evokes her in the legend ‘Present mirth hath present laughter’. It’s impossible to review Ketterer’s Men objectively, because to do so is in some way to review the spirit of Lizz herself; the company’s joyful and cheeky sense of humour, its soulful attention to emotion, its gentle but deeply affecting musical sensibility – these are my memories of Lizz and my experience of Pericles.

This was also a reunion for me with Pericles itself, which I’ve not see staged since 2006, in the RSC’s wonderful promenade version, despite writing the stage history for the RSC edition. When I last saw it I was an MA student at Warwick, halfway through the Complete Works Festival that occasioned this blog, inexperienced in Shakespeare and experiencing the thrill of discovery and new beginnings in many aspects of my life. A lot of life has happened since then, and I return – like Pericles himself – older, wiser, sadder and calmer. This may sound personal, but Pericles is a personal play, a play which forces its characters to revisit themselves across the gulf of time, to return to who they were and acknowledge the transformations that have taken place, and to experience afresh emotions associated with the person they left behind. At the end of this production, as the cast held up letters spelling out ‘FOREVER HERE’, the reference to Lizz was clear, but even more potent was the reminder that the whole idea of a ‘homecoming’ is of returning to a place which a part of you has never left. Home is where the heart is, home is where the hurt is.

Peter Malin anchored the play as Gower, reading the Choruses from a weighty tome and, gradually, losing himself within a play that he couldn’t retain an emotional distance from. Following Thaisa’s entrance into Diana’s temple and the loss of hope of reunion, the production’s first half ended with Gower leaving the stage, silently and frantically turning over his pages, looking for an answer. This searching was revisited throughout the production in key motifs – the sail that dominated the downstage end of the traverse stage; the soundtrack of creaking beams and gulls that pervaded the production; the wistful folk of Jenny Went Away, whose songs and settings orchestrated the yearning that underpinned the performances.

Pericles, played by Charlie Morton as a nervy, often uncomfortable young ruler, wandered through the play’s various worlds and was acted upon rather than an actor in his own fate. Crucially, even in a hysterical Chariots of Fire race sequence that stood for the jousting, it was the other knights that tripped each other and fell, rather than Pericles who excelled. Pericles instead encountered larger-than-life characters: the booming, articulate and overreaching Antiochus of Peter M Smith; the cloaked, dignified yet playful Simonides of Jose A Perez Diez; the scheming, swaggering Dionyza of Cecilia Kendall White. If imagined as an Everyman figure responding to the ebb and flow of waves disturbed by these more powerful figures, Pericles became an avatar for the production’s evocation of loss.

Loss is dependent on a sense of what is being lost, of course, and Jenny Bulcraig established this through a coy, knowing performance as Thaisa, playing her father’s games while also making clear to the audience through her gaze and somewhat breathless pauses her own designs on Pericles. Diez’s avuncular Simonides brilliantly captured the nuclear family at the heart of his court, and the two’s amused and dismissive reactions to the boastful posturing of the other knights ensured this was a family whose value could clearly be seen. The giggling asides of Simonides even as he ordered Pericles to kneel in disgrace before him were a comic highlight; yet the awkward first dance of Thaisa and Pericles, stepping delicately around one another, managed the difficult feat of realising their connection before the too-quick separation.

The emotional throughline continued in the awakening scene, which allowed the music to linger long before Thaisa finally awoke under the calm administrations of Louis Osborne’s Cerimon, and most powerfully in the reunion of Pericles and Laura Young’s Marina. The two were kept kneeling at a distance from one another, Morton nailing the impact of every confirmation in Marina’s speech, joy and grief overwhelming him to the point where he was unable to speak to reassure the disconcerted Marina, who remained unknowing yet participatory in the groundswell of emotion. This centrepiece scene, performed without gimmickry but with unbridled emotion from the cast (including the equally affecting, quiet realisation of David Waterman’s Helicanus), almost unbalanced the production in its impact, teasing out suspense and the process of grieving in a way the final reunion with Thaisa could never hope to equal (Shakespeare’s fault, not the production’s).

While the haunting sense of loss was the production’s main strength, however, this was a largely comic production. From the actors posing as throttled heads who acted as a macabre back-up group for Antiochus’ Daughter, to Jen Waghorn’s succession of sarcastic messengers and sycophants, to Will Sharpe’s bushy-bearded ‘avast’ing Pirate and Osborne’s Igor-channelling hunchbacked Thaliard, the production balanced its sincerity with a population of grotesques who collectively evoked the cruel world in which Pericles and his family were forced to operate. In these comic scenes, anything went: slow-motion racing, drinking games in dumbshow, peeved prostitutes, guffawing flatterers. Chris Gleason’s shrug to the audience after Marina was torn out of his hands by a gang of pantomime pirates was priceless.

The more consistent and cohesive comic strand, set in the brothel, established a more consistent aesthetic. Lit by red light and dominated by Smith’s towering cross-dressed Bawd, in death-defying heels and legs longer than Marina herself. Waterman’s string-vested Pandar and Ronan Hatfull’s rudeboy Boult presided over a chorus of sleazy prostitutes and keen customers, who had to fight to extricate themselves following their conversion by Marina. Young became a still presence in the middle of the debauchery, clear-voiced and earnest. The intimidation of her circumstances was clearest in Smith’s overbearing, towering performance, which gave Marina no room to move or breathe. In this den of vice, Sharpe’s Lysimachus was initially exposed as hypocritical lecher before being won over, and his calm, gentle presence felt key to Pericles’ own revival, establishing the terms on which Pericles and Marina could meet.

A special mention has to be made of Gleason and Hatfull who, despite joining the production at the eleventh hour, were seamlessly integrated into the ensemble. This was an accomplished and moving take on Pericles, channelling the investment of the company in the charity’s aims into an amusing, irreverent but also challenging exploration of grief, rediscovery, loss and healing. But perhaps most importantly, as the cast held up their placards to read ‘FOREVER HERE’ in the final image, it was a reminder of an absent presence to be celebrated as well as mourned.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply