October 28, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Michael Grandage Company) @ The Noel Coward Theatre

Michael Grandage is an excellent director, particularly of actors. His Othello at the Donmar some years back provided what may prove to be a definitive Othello in Chiwitel Ejiofor, and his Lear starring Derek Jacobi in the same venue found rare intimacy in the play against a stark backdrop of boards. Yet as Grandage leaves behind the Donmar for the West End, something horrible has happened. His Twelfth Night was one of the least inspired, most routine productions of a play given to uninspired, routine production I have ever seen, and his Hamlet a huge disappointment, trading off a celebrity actor but otherwise going through the motions. Now, Grandage manages his own company with an enormous West End residency and an even greater focus than ever on star actors leading West End-friendly productions. If the Dream, the first of the company’s two Shakespeares, is anything to go by, the move may be taking Grandage even further towards commercial success at the expense of interest or insight.

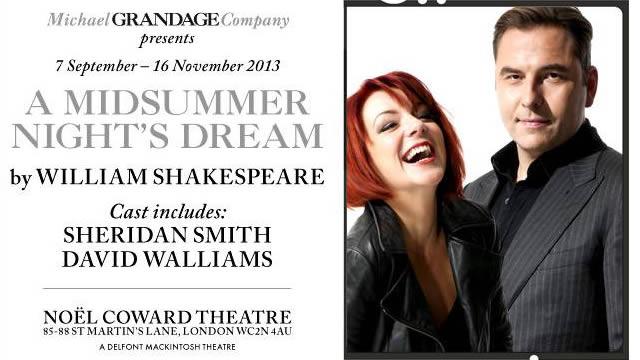

To build a Dream around star performances is in itself an odd move, but Sheridan Smith (Titania/Hippolyta) and David Walliams (Bottom) dominate every piece of advertising. Both were a huge disappointment, and neither should be held accountable. Smith was given nothing to do as Hippolyta in an interpretation almost offensive in its reluctance to engage with the character’s position. Defeated then married, sidelined but implicated, Hippolyta’s backstory frames the opening action of the play, yet Smith’s performance rendered the character entirely inert and subordinate to Padraic Delaney’s bizarrely affable Theseus, who seemed content to chat pleasantly about Hermia’s possible death sentence.

Smith was much more interesting as Titania in a forest modelled after fire-worship ceremonies of the ’70s, in which fairies smoked dope and tripped out, wore beads and shades, and generally shaped a counter culture in opposition to the more uptight court. While the press and programme materials trumpet this production’s sexuality, however, this was one of the chastest Dreams I’ve yet seen, going little beyond the occasional penis reference for huge laughs while burying all of the innuendo surrounding the ‘crack’ between the Wall’s ‘stones’ or the potential sexual implications of a well-hung ass. Smith was called upon to dominate these scenes and did fine work in managing her troupe of stoners, but there was little here beyond a pretty set and costumes.

Walliams, meanwhile, relied on a one-joke performance (Bottom is camp, ergo funny) to pull together the Mechanicals’ scenes, which were otherwise completely underdeveloped. Richard Dempsey was a gay Quince slightly in love with Bottom, Craig Vye a mildly confused Snug, and Alex Large a nervous Flute, but there was no attempt to play the Mechanicals as anything other than enthusiastic amateurs. Walliams interacted well with his audience through understatement in his direct address and beautiful timing in his pregnant pauses, but the device became tired and overused. To portray a Pyramus taking too long to die is a balancing act, and in drawing out this drawn-out death interminably, Walliams out-Bottomed Bottom, moving self-indulgence from the hilariously parodic to the tiresomely dull.

Yet the faults of this production were not the cast’s. Walliams and Smith both did fine work within the remit given, and the supporting cast had gusto. Leo Wringer made for a cantankerous and nuanced Egeus, thrown by the shifts in allegiance and last seen throwing Hermia a hurt look of rejection after the newly awakened Demetrius had rejected her hand. The lovers managed the usual physical comedy fine: Hermia was picked up and held at arms’ length, Lysander and Demetrius performed the standard pratfalls, and Katherine Kingsley’s Helena did some fine and interesting work in attempting to rip off Demetrius’s pants and throwing herself clumsily and gracelessly at his feet.

The fault was instead in the production’s utter conservatism. At the level of gender politics, the production felt like a throwback – even Helena and Hermia were required to sit at their husbands’ feet during the wedding entertainments. Hippolyta was silenced, Titania’s tryst with Bottom was moved past as an inconvenience without question, and the feud over the Indian Boy was barely alluded to. ‘Camp’ was funny, as was the frisson of men fancying other men alluded to but never forced upon the audience. The Bakhtinian carnival here existed solely in order to facilitate the return to an order that was never really challenged in a Dream that avoided threat, danger or subversion beyond the sight of fairies smoking.

A Dream need not be dark, of course, but it should at least be funny. Yet disappointingly, given Grandage’s pedigree with actors, the jokes were thrown away – a horrendous misplaced emphasis on Lysander’s ‘Do you marry him[?]’ turned it into a question rather than a witty put-down, and the rest of the production seemed uninteresting in mining any deeper than the surface of the text to find the play’s humour. The sensation throughout was of laughter as choreographed as the play itself, with not a single surprise or innovation in the telling, aside from the somewhat amusing collapse of the dying Thisbe into Pyramus’s crotch and Bottom’s hand rising to make sure Flute’s face stayed in place.

But, of course, this production wasn’t for me. Grandage has realised, presumably, that there is an enormous audience of West End theatregoers coming to their first Shakespeares, drawn by the thrill of celebrity casting and the promise of an inoffensive, decent and mercifully short (a hair over two hours) night out. Judging by the hysteria of the audience, this production was a resounding success, a joyous and surprising evening. It’s testament to Shakespeare, of course, that a production that chose to stick so rigidly to the basic template of Dreams could be received as fresh. My own desire for innovation and originality comes from a belief (ethical? perhaps) that theatre should always be ‘new’ even when dealing with an established play, but I appreciate many would argue that the classics deserve to be seen in a conservative shape.

A beautiful looking production was testament to Christopher Oram and Paule Constable’s work on set, costume and lighting, creating a wonderful twilight world for the hippy fairies made up of dilapidated furniture and rubble, and an eerie image of their hands pressing against the windows of Theseus’ palace at the play’s conclusion. The entertaining dance between Oberon and Titania that marked their reunion, complete with backing dancers, was a highlight, as was Walliams’s stoned giggling at the names of the fairies attending on him. But the overriding sour taste left in my mouth was of a play rushed through as efficiently and superficially as possible in order to offer a clear and crowd-pleasing version. Slickly polished, carefully inoffensive and designed to appeal to the broadest possible public, this was Shakespeare as commercial product. It’ll enthuse a great many first time audience members about Shakespeare, but I can only hope that the upcoming Henry V sees Grandage back on the questioning, insightful form he has shown in the past.

[…] the underwhelming and frustratingly conservative Midsummer Night’s Dream, I didn’t have high hopes for the second Shakespeare in Michael Grandage’s West End […]