October 8, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

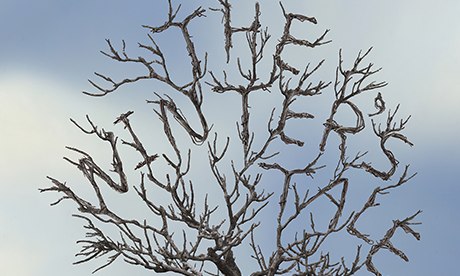

The Winter’s Tale (Sheffield Theatres) @ The Crucible

I’ll confess to my heart sinking somewhat as the cast of Paul Miller’s new Winter’s Tale emerged onto a bare thrust stage in Edwardian suits and European royal military uniforms. Almost as much as Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale seems to me to have become stuck in an era that doesn’t seem to me to do much to elucidate the play, particularly when the correlating scenes in Bohemia inevitably end up becoming a much vaguer evocation of a nineteenth-twentieth century rusticity. Sheffield Theatres continued in its recent tradition of solid but somewhat uninspired Shakespeares with a production that, like its setting, fitted but did nothing new.

The first half was strong, although many of the cast struggled for clarity against the odd acoustics of the Crucible that saw the whispering of characters having private conversations almost completely audible but failed to carry Leontes’ voice during his ranting. Daniel Lapaine was an unusually young and petulant King of Sicilia, brattish in his mocking laughter at Paulina and scornful in his treatment of Hermione. His shocking gestures included taking Antigonus by the nose, replicating his infantilising treatment of Mamillius, and lounging in a throne for his casual reception of Paulina.

Claire Price’s Hermione, the standout of the company, was clear and humane throughout, a proud and uncomplicatedly forthright public figure whose accusations, defences and oaths rang out truly through the space. Her ability to weather what befell her was her strength-while her maid collapsed in tears, Hermione treated Leontes’ earlier accusations as a joke for as long as possible, before sweeping out with her women in protest. While almost every other production of the play i have seen in recent years has made her stand trial in her birthing clothes, here Hermione was cleanly and smartly dressed, a confident and upstanding presence to counter the rattled Leontes.

With this dynamic at its core, the first half of the play rattled along at a fine pace. Solid support came from Jonathan Firth’s crisp Polixenes and Barbara Marten’s powerful Paulina, the latter in particular a potent presence, sweeping through the stage and cowing the young servant tasked with removing her from Leontes’ presence. At times the production even veered towards potentially shocking decisions: while the fake baby that cried and even rocked independently when laid on the floor was a little amusing, it meant that the moment when Leontes drew his sword and used the point to shift its hood for a better look was genuinely disconcerting.

A pleasing focus was on the bonds between women throughout, including between Paulina and Emilia under the watchful eye of a softly spoken and moving Gaoler and in the physical support granted to both Hermione and Perdita by their respective attendants in both halves. It was particularly gratifying to see Mopsa and Dorcas join forces in support of Perdita after Polixenes’ intervention.

Yet the production measured itself too carefully, particularly in a trial scene that sat all of its onlookers on large cushioned chairs and thus struggled for dynamism. In the evocation of an early twentieth century European decorum, the production sacrificed energy, a cost that was particularly apparent when the play returned to Sicilia for the closing movement. This production saw no problem in the conclusions to the play nor drew particular magic from the statue scene, instead leaving Act V as a slow, pleasant tying up of ends resulting in a harmonious and entirely happy joining of hands organised by Leontes. The redemption and happiness felt unearned, and the conclusion lacking in dramatic impetus.

The Bohemia scenes, meanwhile, fell very flat despite some hard work by the cast, notably Keir Charles as an Autolycus who played two ukuleles, wore a trenchcoat covered in ballads and winked at the audience in his pursuit of the scene’s ladies. Mopsa and Dorcas both fell desperately in love with him as they sang a pleasing ballad together, and his gentle charm was a welcome relief from the calm elsewhere. The other triumph of these scenes was Patrick Walshe McBride’s high-pitched Young Shepherd, an able gull to Autolycus and an extremely entertaining ‘gentleman born’ when the time came, affecting a posh accent that exaggerated pronunciation of long vowels and offered a non-ironic place to Autolycus.

While the performances worked, however, the atmosphere of the sheep-shearing was almost entirely absent. An enormous sheep’s head dominated on a platform around which the dancers gathered, but even though the stage was filled with the entire cast in masks and costumes, they still for the most part stayed stuck in one place and listening to the central conversations. Given the energy put into this play in recent years by the RSC and Propeller, the static quality of these Bohemia scenes felt particularly pronounced, and their celebrations too contained and formal. While the dancing and singing were excellent, they sat as oddly isolated set pieces rather than growing organically from the scene.

This was, in the end, the production’s problem. Moments of potential (the Bear, entering on all fours to lope around the edge of the stage amid flashes of lightning) were followed by deflations or disappointments (the Bear ran comically off stage rather than continuing in its menacing prowl). The bare stage felt like lack of imagination given the tired setting rather than a push towards efficiency, especially given the length of some of the scene changes. And the momentum built up in the first half was entirely lost in the second, which meandered towards a conclusion that seemed too nervous to say anything about the play. This Winter’s Tale, that is , managed to be much less than the sum of its parts, and while it was sporadically amusing and featured some excellent performative work in its first half, struggled to sustain focus and interest.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply