August 21, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Smock Alley Theatre, 1662, Dublin

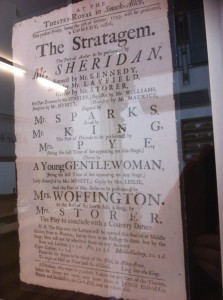

Unbelievably, people forgot that Smock Alley Theatre was there. One of the three theatres (and the only one outside of London) given royal warrant after the restoration of Charles II, Smock Alley is one of the most important theatres in Western Europe. Modelled on the new style theatres in the French tradition, it ran continuously until 1787 and, among other highlights, featured Garrick’s first performance as Hamlet, the debut of plays by Goldsmith, Sheridan and Farquhar, and any number of riots and other incidents. Macklin performed there, Woffington, Sheridan and the other important figures of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century theatre world.

And then it slowly disappeared. For nearly two centuries the building operated as a church, with the front entrance reversed away from the Liffey. As the Liffey receded and the theatre no longer stood on the bank, the building’s original purpose was forgotten, and when the church shut down in 1989 it was some years before scholars and architects realised that the dilapidated church not only marked the site of the original theatre, but had actually been constructed within and on top of that theatre’s shell. Last year, the building reopened as a theatre, and now visitors can see a building still of the original size and shape of the original Smock Alley.

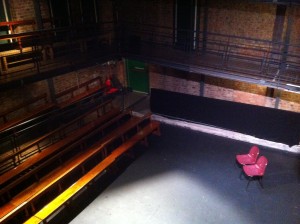

The tour is wonderful – I was privileged to get a one-on-one lookaround the building led by Christina Matthews, the Front of House Manager, who does an extremely entertaining and informative overview of the site, which also includes an old boy’s school, a new banqueting hall (with, I’m told, an excellent lunch service) and the new theatre, oriented at 90 degrees from the original layout and offering an exciting, intimate venue for visiting companies. The space is great – the acoustics are wonderful, the stage is intimate, and the back wall needs to be left exposed for its austere character. Yet the next door school (above) is also a phenomenal space – dark, deep, echoing and hugely atmospheric, and already in demand for concerts and talks.

Yet while the workings of the modern space are obviously going to be key to the venue’s success, as I hope this picture shows, the excitement is really the visibility of the original shell. The ceiling you can see here has been added as part of the refurb to allow for the banqueting hall above, but from the foyer you can effectively see the whole length, breadth and height of the Restoration theatre shell. Where I’m standing in this picture would, I think, be around where the stage would have come, looking out towards the audience (remember, the new space is reoriented 90 degrees). Far more so than the ‘ghostly’ feeling of the Rose on Bankside, this is a piece of theatre architecture that lets you imagine the three-dimensional environment of the original space.

The building is haunted (obviously), but it’s a treasure trove for theatre historians. The foundations of the building are clearly visible, and you can even go into the crypt left over from the church and see the mysterious sarcophagus that rests on them. Most of the venue’s visitors are expats coming to see the old church, but all through the combination of Restoration theatre, 19th century Catholic church, old school and modern theatre is exciting and rich. The building is already hosting writing and theatre festivals, and needs to be better known.

If you’re able to pop down, it’s on the banks of the Liffey, just west of Temple Bar. The enterprise needs scholarly and professional support, and I’d urge you to pay it some attention. Hopefully it’s going to become an increasingly vibrant part of Dublin’s theatre scene, but I suspect there’s also exciting research to be done.

I’ll be there tomorrow–it’s all so amazingly grand! Thank you for this post, Peter!