July 21, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

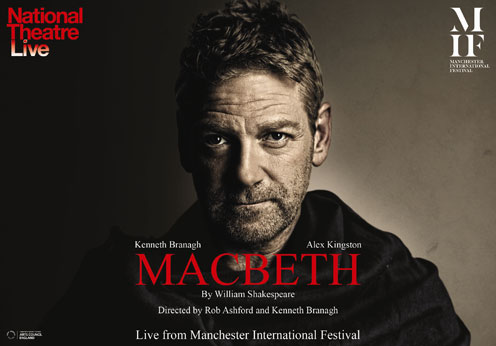

Macbeth (Manchester International Festival) @ NT Live

The camerawork for the NT Live screenings has developed extraordinarily since the project’s early days. Covering Kenneth Branagh and Rob Ashford’s Macbeth, cameras swooped over the action, fast editing gave a kinetic and chaotic insight into the battle scenes, extreme close-ups caught beads of sweat and tears on Macduff’s face, and the slow pans to sections of the deconsecrated church in which the production was staged directed the audience to the ethereal and sacred concern with the nature of good and evil. As a cinematic broadcast of a live event, the NT Live editing team are setting incredibly high standards, even if at times there still needs to be more generosity shown towards reactions to lines as well as their delivery.

This was, then, an exceptional broadcast of what turned out to be a disappointingly standard production of Macbeth. The key innovation was the found space, performed in muddy traverse between seated banks of spectators, the narrow trench becoming a convincing battlefield, an emblematic spiritual battleground between the high altar at one end and the gargoyle-like, mud-speared witches peering out of hatches at the other, and an intimate space for domestic scenes. As cast and audience got progressively muddier, one couldn’t help but miss the obvious intention that mud levels all sides in a conflict and progressively taints people. It’s a metaphor that Branagh famously used in his Henry V, and it retained its powerful clarity.

As ever, though, the difficulty with Branagh’s staging is the need to visualise everything. Not only were several daggers shown during Macbeth’s soliloquy, literalising his gaze, but also the murder of Duncan was staged in full, allowing us to see John Shrapnel’s King turn to Branagh’s Macbeth and beg for his life before Macbeth repeatedly stabbed him and left him spread out in his bed in a pose reminiscent of the death of Marat. In the bid for visual literalness, the production allowed little space for audience interpretation, and this was enhanced by the sheer speed of the production, played through in a little over two hours with no interval. While there was a reasonable amount of cutting, the emphasis throughout was on efficiency at the expense of pause, nuance or reflection, leaving this a brutally concise and hard-hitting Macbeth that didn’t offer much new in terms of understanding the play.

Dressed in kilts and wielding claymores, the production aimed for a Braveheart inflected vision of Scottish history, including several actors who spoke with Scots accents. Visions of masculinity were prominent throughout, particularly in a climax which saw Malcolm surrounded and swords raised as the newly created earls hailed the new King of Scotland. Blood and mud combined in graphic stabbing scenes, such as the laying out of Pip Pearce’s Young Macduff and the brutal vision of the mutilated Duncan. The setting of the church, of course, acted to offset this throughout, with constant appeal to the stained glass windows when God was referenced, and the pouring of light through them for the England scene.

Branagh’s Macbeth was a personal, emotional one, strongest when weeping uncontrollably upon hearing the news of Lady Macbeth’s death. The production’s physical intimacy (the irritating self-fanning of the live audience was very distracting from my cinema seat) brought the audience close, but didn’t translate to a huge amount of direct address – although Macbeth frequently appealed to the seats, this was a man lost in his own world, shouting out rather than asking genuine questions. While Branagh’s committed yet often fragile king offered an interesting reading of the character, the production didn’t seem quite to know what tack it wanted to take, juxtaposing these tender moments with deeply emblematic staging that, for example, saw Daniel Ings’s Porter introducing a series of writhing bodies at the ‘Hell’ end of the auditorium. In terms of overall cohesiveness, the two angles rather cancelled each other out.

There were strengths throughout. The England scene was compelling, with a convincing and upright Malcolm (Alexander Vlahos) whose lying was directly connected to concern for his nation. Rarely have I seen a Malcolm shout, but this young king-in-waiting was a persuasive leader, deeply invested in the hurts of his country. Ray Fearon’s Macduff tended a little closely towards bellowing at times, but was a truly intimidating presence on the battlefield. Deep-voiced and pacing the stage in fury, he seemed ready to snap Malcolm’s neck at one point, but was also quick to humble himself before his king. A rare pause was allowed to give Fearon full space to vent his grief, his voice moving up several pitches and finally building into a full-throated roar. ‘He has no children’, in particular, became a plea, a moment of incomprehension of how children could become involved, and of realisation that Macbeth could never feel the pain he felt currently.

The weak link was Alex Kingston’s Lady Macbeth in what came across to me as a showboating performance, unnecessarily loud and artificially gestural. Kingston’s uneven tone relished the language, enunciating every word as if a performance in itself, but this presentational performance contrasted sharply with the psychological intensity of Branagh’s. The nadir was a sleepwalking scene that instead went for a crude show of schizophrenic frenzy, veering between different personas and voices while standing aloft, and striking dramatic poses of grief, supplication, rage and hand-washing. In the quieter moments, particularly when acting with Branagh, the performance was reined in and there were moments of connection as she described having given suck, but along in soliloquy the staccato mode of delivery, punctuated by specific gestures for each line, was unpleasant to watch. The style was echoed in the witches, hysterical and ecstatic without obvious purpose, and using speech patterns that drew attention to their arbitrary slippage between booming and giggling. The overall impression was of a production that had very little interest in its women, though Rosalie Craig was a brief, potent presence as Lady Macduff, resisting the murderers with unusual strength before having her neck snapped.

Setpieces were suitably spectacular. A huge bank of flames rose on the altar as the witches called up their familiars, and a writing mass of bodies covered by a sheet appeared in the centre of the stage, communally uttering the prophecies before eventually yielding a line of marching, kilted future kings. Terry King’s rain-soaked fights launched the play on a high-octane note, and the sober, staring presence of the Ghost of Jimmy Yuill’s Banquo was a high point, Branagh shaking the tables of the banquet as he fell onto them, shuddering.

The production was a particular triumph for NT Live, showcasing the team’s facility with live recording and editing, turning a visually arresting production into a stunning cinematic event. Yet the distance created, particularly with a production that clearly relies on physical intimacy, exposes the unbridgeable aspects of atmosphere, volume and audience participation that can’t be replicated in the cinema environment. While the production has clearly been a success, for me the cinema showed up weaknesses that would no doubt be diminished in the live setting where the mud, rain, smells and sounds of the found space would contextualise the overly loud performances, the excess in acting style and the rather straightforward visual images.

Apologies for the ‘irritating self-fanning’, but it was over 30 degrees in there!

[…] but more generally, there was none of the dynamism that characterised the filming of Coriolanus, Macbeth or Frankenstein. Not since Phedre have I felt so frustrated by the limitations of the […]