April 21, 2013, by Peter Kirwan

Caesar Must Die (dir. Paolo Taviani & Vittorio Taviani)

Italy’s official nomination for the 2013 Best Foreign Language Oscar is an extremely odd beast. Ostensibly a fly-on-the-wall documentary following a group of Italian prisoners putting on a production of Julius Caesar, the film is framed by the climax of the real production, as Salvatore Striano’s Brutus seeks a willing hand on whose sword to fall, before a standing ovation greets the jubilant actors. In between, and in black and white, the film depicts the rehearsal process as actors experiment with their lines, discuss the plot, are watched by guards and have various internal disputes along the way.

This is no Shakespeare Behind Bars, however. While the actors are real prisoners and the climactic theatre performance appears to be real, the remainder of the documentary is clearly staged: intimate close-ups, multiple cameras and a cleanness to development bespeak a rehearsal process that has been posthumously reconstructed, the prisoners playing out a neatly narrativised version of their experience exploring the play. There is nothing in this prison beyond the rehearsal process; guards lazily allow the cast to rehearse past shutting-out hours; the recreation spaces are eerily empty; and the prisoners (with one carefully contained exception) are uniformly engaged with both play and the authorities permitting the process.

For a film set in a prison, there is remarkably little conflict. The back stories of the prisoners are briefly alluded to but forgotten very quickly, the only key reference being Striano’s emotional reaction to a line that takes him back to drug-dealing days. While several of the prisoners had connections to the Mafiosi, the particularities of Italian politics are avoided in favour of a more general narrative of self-improvement, with no specific lessons learned. In some ways this is an important counter to the Hollywood backstage drama genre – there are no easy arcs here. The downside is that there is precious little connection to any of the prisoners or an exploration of what it is they feel they are getting out of the production.

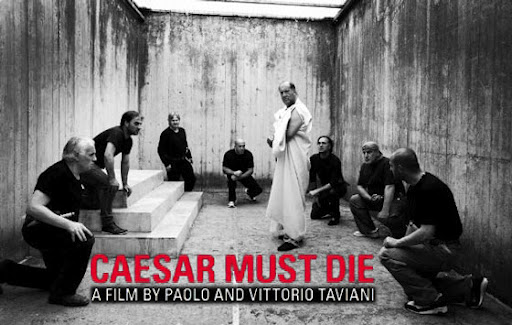

The cinematography, however, is beautiful. In stark colours, the prisoners are escorted in and out of their individual cells, brought into neatly ordered lines and left staring through blindingly bright windows. The sense of constriction afforded by the prison becomes key in a deliberately site-specific rehearsal process that plays out scenes in key locations around the prison. The assassination itself (picture above) takes place in an external area, the ‘public place’ of the prison with other prisoners milling outside and scattering in staged confusion after the murder. Meetings of the conspirators are held in cells; the initial conversation between Brutus and Cassius sees Striano choosing to sit slumped against a wall while Cassius (Cosimo Rega) looks ambitiously out from his bars.

Prison life is occasionally evoked. In a moment that feels interjected in order to make the point that these are prisoners with their separate interactions, Giovanni Arcuri and Juan Dario Bonetti break off from their scene as Caesar and Decius and begin threatening each other over their politics. They leave the room, much to director Fabio Cavalli’s distress, returning to the room a few moments later having resolved their dispute. Moments such as this cry out for more attention from the documentary team; the neatness of the interventions of the documentary element leaves it fundamentally irrelevant. More interesting are the moments in the first readthrough during which the actors debate the correct accent for the play. Cavalli encourages them to perform in their natural voices, with much debate of the relative connotations of Neapolitan accents in particular informing the actors’ work as they begin inhabiting their characters. There is plenty of amusement from Francesco Carusone as the Soothsayer, with a habit of putting his finger to his face, and from Vincenzo Gallo (rooming with other actors) as Lucio, complaining about his role requiring little more of him than lying down.

The finest scenes are reserved for the orations, as Striano and Antonio Frasca (playing Antony) take turns in the courtyard of the prison while they are watched from above. The crowds are remanded in their cells, banging on their bars and screaming for justice. There is no space within this set-up for depiction of a riot, regrettably, and the female roles are ignored entirely – neither production nor documentary takes any risks. Other than the late introduction of a near-silent actor to play Octavius (another of the rather-too-neat coincidences that belies the documentary form), the film winds uneventfully to its close, cutting to the theatre production with its surprisingly innovative physical sequences (actors hold up ramps for the key characters in the battles), climaxing in Brutus’s death at the hands of the enormous Strato (Fabio Rizzuto) who sobs over his body.

What emerges from the production is the closeness of Cassius and Brutus, with Rega’s performance in particular bringing out the conflicts within the system. Arcuri, as the arrogant Caesar, allows the character to become a prison don, although this isn’t over-emphasised; his relative isolation from the other prisoners is what matters. As the prisoners bond over a form of community, the documentary’s downbeat close acts to re-isolate them. Moving from the fashionable Italian audience who give them an ovation and the scenes of the actors hugging delightedly, we are then treated to a coda which sees the main cast members, one by one, being locked up in their individual cells. As Rega re-enters his room, he sighs and announces that ever since doing the play, the cell has become a prison. As staged as this final moment is, it speaks to the humanist message that underpins this documentary, the humanity that languishes behind the locked cells. The report at the film’s end that the main actors have gone on to become actors and novelists is, perhaps, a rather anticlimactic piece of information, but one that underlines the import of a process which, even if artificially recreated, has been of enormous benefit to the participants.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply