April 30, 2011, by Peter Kirwan

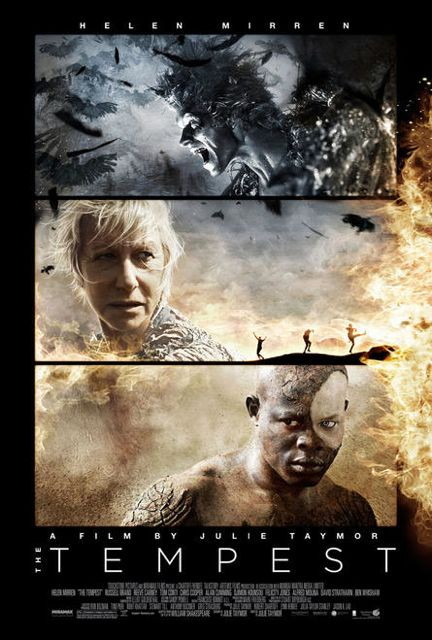

The Tempest @ Warwick Arts Centre Cinema

Julie Taymor has had a rough year. She’s a favourite director of mine – I love her Titus and Across the Universe, and she’s borne herself pretty well through the fiasco that has been (and continues to be) Spider-Man: The Musical. It’s true, too, that we need a good film of The Tempest. Derek Jarman’s classic has such a specific agenda that it limits its use and relevance; the BBC version is horrifically bad and Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books is an arthouse deconstruction. So I had high hopes for this (heightened by an amazing cast) and really wanted to love it. Goodwill can only run so far though, and unfortunately I can’t honestly say I found anything at all to like about this film.

The film started promisingly. It began with an elaborate sandcastle sat on the palm of a hand stretched out towards the ocean. The skies darkened, and rain began to pour, disintegrating the castle. The owner of the hand – Felicity Jones’s Miranda looked, panicked, as a passing boat was caught in the storm, and the furious, chaotic scene on the boat was interspersed with shots of her running, full-tilt, along the coast to where her mother, Helen Mirren’s Prospera, was holding out a staff. The destruction of the ship was cinematic and powerful, especially as Reeve Carney’s Ferdinand locked himself in his cabin to pray and was then swept out by waves smashing through his windows and pulling him into the ocean.

Nothing else in the remainder of the film, sadly, lived up to this opening. The film gave an entirely conservative reading of the play, with only cosmetic differences and few interpretative decisions beyond the obvious. The changing of Prosper’s gender (she was the wife of the Duke of Milan) made no difference to the character, who remained a kindly but occasionally brusque mother, a strong-willed master and a stern opponent to the conspirators. Mirren was one of the film’s stronger assets, particularly in the scene of abjuration where she pulled a ring of fire around herself and grew powerful as she described her earlier feats, before allowing the flames to die as, exhausted, she offered to drown her book. She worked in a laboratory filled with mechanical equipment, mirrors and beams, and wielded visual and powerful magic throughout, behind which the character was somewhat buried. Flashbacks to a fuzzy council room in Milan confused rather than clarified her long opening story.

Her assistant was Ben Whishaw as Ariel, who first appeared staring out of a pool lovingly at his mistress. I say ‘his’, but this Ariel was androgynous and softly-spoken, a flitting spirit. Whishaw was excellent, touching in his voice and, especially on "were I human", cutting through the visual style with moments of emotion. However, his performance was served badly by abysmal visual effects. Whishaw was never quite localised within the shot, instead looking like a two-dimensional imposition across the picture. While the producers aimed for spectacle – a fiery giant tossing the ship between his hands in a flashback; a face peering out of trees and ponds; a screaming harpy accompanied by thousands of birds (this was genuinely terrifyhing); or the flame-faced courser of hounds – the picture of Ariel never quite fitted the action or interacted with it genuinely, and the over-use of blended figures for movement and multiple copies of the same actor looked cheap and tacky.

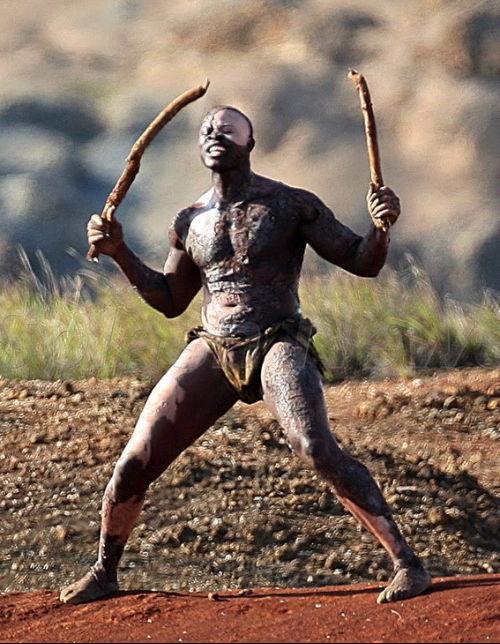

Djimon Hounsou was an entirely traditional Caliban, the decorated black man wearing loincloth and a thick African accent (which was, for much of the film, unfortunately unintelligible). Hounsou brought a dignity to the character in the early scenes which was abandoned entirely by the time of his union with the clowns; although a strong climax saw Prospera and Caliban face off at each other silently across a pond before he quietly turned his back and left her cell. The interpretation hedged its bets and left Caliban rather superfluous, neither a heroic victim nor a savage villain but merely someone who lived on the island and occasionally interacted with the plot.

Better were Alfred Molina and Russell Brand as Stephano and Trinculo. Brand started poorly, with clowning and audience banter that would have worked well in an intimate stage setting but, in the massive empty space of the desolate volcanic island, sounded hollow and forced. Molina’s early appearances, stumbling through a canyon and murmuring to himself as he sipped at his bottle, were far more suited to the format. The two men worked well together, and Brand’s ad-libbing was particularly welcome in a very boring film, but the insertion of urination jokes and extended cross-dressing scenes were obviously extra-textual.

The courtiers were all fine, but their scenes of walking through trees and rocky cliffs were exceptionally dull. Their madness following the spectacular harpy scene was well played, however, with David Strathairn’s Alonso stumbling lost and Sebastian and Antonio swinging their swords desperately at invisible birds. Tom Conti was a very strong Gonzalo, too, pacing mournfully after the distracted nobles and weeping. The two young lovers were excruciatingly wet, exchanging soppy looks and doing little more than looking pretty, even in Ferdinand’s interpolated song of "O Mistress Mine" to his new wife. In place of the masque, Prospera showed them a bizarre planetarium-style spectacle of sexual positions being enacted among the stars, which she interrupted quietly herself.

The visual effects, as already mentioned, were variable, and too heavily relied upon. The best were the flaming dogs who pursued Trinculo, Stephano and Caliban, but even these didn’t quite occupy the physical space in which they were running. The rest of the chaos was shown through crazy camera angles, dissolves and fast edits which felt gimmicky rather than organic to the action. The music throughout, too, was disconcertingly eclectic – wonderful rock beats came in now and again to augment the orchestral score, but at times which seemed unsuited to the events and often competing with the text. The textual editing was fine and relatively clear, but with occasional "Why?!" moments such as the Americanism of Prospera’s line "We will go visit with Caliban", which not only sounded odd in an English accent but made the line unmetrical.

This film will endure as the most straightforward and accessible version of The Tempest yet committed to film, and I won’t deny that it’s a watchable version. However, it offered little new to the play other than style, and I struggled to see a good reason for its existence. There were some lovely images towards the end – Prospera’s glass staff smashing against the rocks, and the closing credits which saw books (unseen for the rest of the film) sinking through the waves while a voice sang the Epilogue in a tuneless style – but these couldn’t make up for such a tired film. Here’s hoping for better things with Coriolanus.

I agree with all you say, particularly the strange visual effects used for Ben Whishaw. In his post-screening discussion, Jonathan Bate (Script Consultant) revealed that the film was shot in three weeks on a Hawiian island. Ben Whishaw (who Julie Taymor had wanted for the part since seeing him play Hamlet) was in another stage play so was unavailable. As such, nearly all his scenes were filmed against a green-screen in a studio after the main shoot and he was editied in later, which accounts for his dislocation. The only scene where he was actually in the room with his screen partner was in the ‘were I human’ scene, which you mentioned for being particularly connected, because Taymor decided that she wanted that scene to be “real”, even if she couldn’t have the others so.

Jx

Top info James, thanks for this! I’d heard that he hadn’t been on location, so was surprised to see him so “present” during the ‘were I human’ scene, which was by far the most effective. Even with the logistical difficulties, I’m still shocked in this day and age that they couldn’t come up with something more convincing for the remainder of the film though.