February 9, 2022, by Peter Kirwan

Hamlet (Guildford Shakespeare Company) @ Holy Trinity Church, Guildford

This review is of a preview, after press night was delayed.

A week or so ago, The Stage awarded its ‘Unsung Heroes’ honour to all understudies, in recognition of a year that has not only seen planned understudies and swings working overtime to keep productions going as casts have fallen prey to COVID, but even old theatre employees being dragged back, sometimes years after having last played a role, to ensure the show goes on. The Guildford Shakespeare Company’s Hamlet had a particularly rough time of it; with only eight actors in the company (nine counting the pre-recorded voiceover of the Ghost), losing four to self-isolation meant postponing the opening and bringing on three script-in-hand former company members to finally allow the production to go before audiences. It’s testament to the professionalism and deep roots of this small company that the scripts rarely proved a hindrance; Gavin Fowler (Laertes and Guildenstern), Chris Porter (Claudius and the Player) and Natasha Rickman (Ophelia, Osric and Barnardo) slotted in so well that, even when there were whole scenes almost entirely populated with understudies, the production never lost a jot of its energy.

The theological underpinnings of Hamlet constitute a major part of the play’s critical history, and staging it in Guildford’s Holy Trinity Church granted Tom Littler’s production a religious grandeur that enhanced its sense of awe. High stained-glass windows along the nave allowed shafts of coloured light down onto the stage that accentuated the gobo used to indicate the swooping shape of the Ghost which flittered around the rood screen and walls. The dimly lit apse of the church, more lavishly decorated than the nave, allowed for deep entrances and exits into what seemed like a more sacred space. The church’s organ allowed for some earth-shaking incidental music (played by Stefan Bednarczyk, doing double duty as an ordained Polonius and the Gravedigger), and the pulpit provided a natural home for Claudius’s and Fortinbras’s (Sarah Gobran) orations to their new subjects. The stability and scale of this permanent set suggested an Elsinore that was indeed a kind of prison, its fixed structures outlasting those who lived and died within it, and resisting even Hamlet’s most outraged complaints.

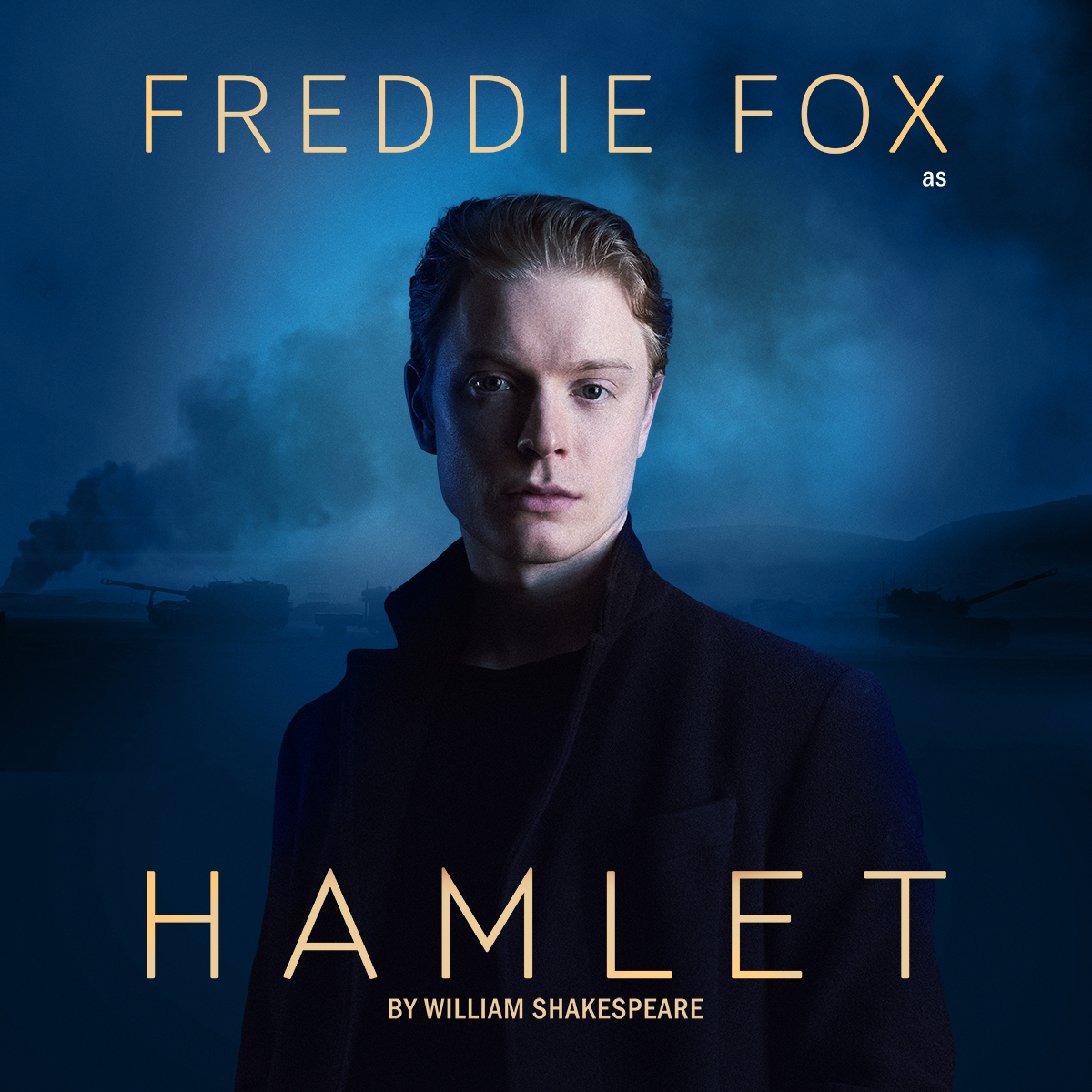

The sacredness of the church setting was stressed in the opening sequence, as Hamlet (Freddie Fox), Gertrude (Karen Ascoe) and Claudius followed the coffin of Hamlet’s father, the aisle imbuing the walk with the solemnity of the real processions that regularly work their way through this space. But Littler didn’t overdo the severity of this Denmark. The priest Polonius was more often fiddling with his phone than pronouncing sermons (the constant texting did get a little annoying after a while – it didn’t feel like there was a strong enough reason for Polonius to be quite so distracted so often), and the security guards who patrolled the night watch with torches were everyday employees rather than militarised guards. Instead, the severity was saved for when it mattered: the arrival of the Ghost. Played in voiceover by Freddie Fox’s actual father, Edward Fox, the distorted voice of the Ghost boomed out from two speakers attached to the rood screen. Bathed in blue light, Hamlet approached the screen quaking, belittled by the volume and uncanniness of something that could easily be equated with the voice of God. It was one of the most effective Ghost scenes I’ve seen in a very long time, utilising all of the space’s acoustic, architectural and visual properties to overwhelm Hamlet, forcing him into a ritual relationship to the divine that shook him to his core.

Fox’s Hamlet was drinking heavily while listening to Claudius greet his new people through a microphone from the pulpit (amusingly, Gertrude took his bottle away from him and replaced it with a champagne glass, presumably suggesting that if he was going to get drunk, he might at least do so in a civilised way); he was still nipping from a flask when he joined Horatio (Pepter Lunkuse) on the battlements. Fox’s petulant voice, sleeked back hair and simple black outfits evoked Draco Malfoy more than anyone else, and what came across most strongly and most surprisingly about this Hamlet was his brokenness. This was a prince who, it seems, had had it all, probably even been spoiled, and now found himself quite absolutely not getting what he wanted. For all that there have been Hamlets who have somehow become inadvertent class warriors or were always rebel outsiders, Fox’s performance implied a Hamlet who had never before had to deal with loss, and whose mechanisms for dealing with it were purely self-destructive. This gave this Hamlet the thrill of being genuinely unpredictable, rather than sensationally so; no forced set-pieces, no spectacular choreography, but a young man so disgusted with the world that he had nothing left to lose.

The most on-the-nose decision was to have Hamlet actually holding a knife to his arm during the first part of ‘To be or not to be’, a decision that certainly gave point to the lines, and which emerged naturally from his earlier self-destructive behaviours, though which seemed a little disconnected from the surrounding scenes in the moment. More powerful, though, was Fox’s treatment of the big speeches as moments of discovery. ‘Frailty, thy name is woman’ was spoken with particular bile; he kept coming back to the audience, as if daring us to contradict him. ‘To be’ followed through a clear trajectory from resolution to commit suicide to a grim determination to live on. At times, when talking about the nature of the Ghost or, most notably, in his final speech, he even seemed to achieve a kind of transcendent revelation, shaking as he prophesied Fortinbras’s ascension to the throne. While his cynical detachment occasionally became a little too arch, the flute scene in particular thrown away with more smugness at the verbal trickery than actual anger at Guildenstern, Fox consistently presented Hamlet as someone who was sincerely let down by the world, and ready to burn bridges.

This led to a certain downplaying of the play’s comedy. The funniest sequences came from Fox dressing up as a priest in order to bless and preach at a bemused Polonius, veering between accents as he worked through different preacher personas in order to keep Polonius on his toes. But elsewhere, the tone of abrupt scepticism muted some of the more obviously funny sections. A notable cut came as the Theresa May-a-like Gertrude asked Polonius to deliver his news with ‘more matter, less art’, to which Polonius simply said ‘I use no art at all’, before silently beckoning Ophelia forward to read her letter. Even the Gravedigger and Osric aimed for a more general casualness/over-formality rather than going for big laughs.

Similarly, the play’s potential for spectacle or melodrama was downplayed, in favour of a human scale of drama. Where so many productions stage horrific violence against Ophelia in the nunnery scene, here Fox’s Hamlet tore up her letter and threw it into the air as confetti to illustrate his instruction for her to be ‘as pure as snow’. The Players were cut down to one actor, who only appeared to give the Pyrrhus speech before Hamlet. Ophelia’s mad scenes involved some sing-song delivery, but culminated in a sober moment as she arranged the other characters as if around a grave, so that they could scatter the invisible plants she had given them in a final quiet blessing. The Mousetrap – in a choice that didn’t make any sense within the diegetic world of the play, and seemed occasioned rather by casting constraints – was a film; the onstage audience sat in chairs facing the offstage audience, with light flickering on their faces and the tinny sounds of a film playing, as Hamlet moved between the onlookers, drawing attention to their reactions to what they were watching. For all that the production’s setting gestured towards the cosmic, the actors’ work kept things grounded in the quiet, immediate, personal experiences that were consuming them.

Despite the fact that so many of the major roles were being played by stand-ins, the performances were uniformly excellent. Fowler had a huge amount to do as Laertes in the play’s second half, including running back and forth from his script while attacking Hamlet over Ophelia’s grave and while fencing him, but his righteous fury and quiet dignity in death made him a grounded mirror in which Hamlet seemed to see himself, occasioning the acts of empathy which saw Hamlet cradle his one-time rival as he died in an act of reconciliation. Porter, meanwhile – while sometimes getting stuck behind the large bit of set that seemed to be primarily present as a shelf for drinks, but did block quite a bit of action – was a beautifully conflicted Claudius, investing huge amounts of energy in trying to gloss over uncomfortable moments and sweep everyone along in his waves of enthusiasm, but conflicted in his own person; his two big soliloquies – in the praying scene, and as he called on England to kill Hamlet, a speech which ended the first act – emphasised his driving agency.

The production’s balance between the profound and the mundane, the awe-inspiring and the everyday, perfectly characterised an approach which took Hamlet seriously and which saw the potential in the play for a fast-moving tragedy of discovery, resulting in one of the clearest and fastest-paced arcs for the lead character that I’ve seen. And with the church itself bearing witness to the often futile attempts of humans to control their own destiny, and resonating with Matt Eaton’s sound design, this Hamlet repeatedly gestured beyond petty acts of revenge to something transcendent, which Hamlet himself seemed to see in his dying moments. I hope the production only goes from strength to strength as it approaches its delayed official opening.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply