June 17, 2021, by Peter Kirwan

Henry VI, Part One: Open Rehearsal Project (RSC) @ The RSC rehearsal rooms (online)

The RSC has been cautious about its reopening in summer 2021. Where other theatres are beginning to tentatively let socially distanced crowds back into their buildings, the RSC has committed instead to a different kind of programme and a different kind of co-presence. The upcoming The Comedy of Errors will make use of the theatre’s unique location, taking place on the bank of the Avon; and The Winter’s Tale had a full production performed to an empty auditorium and captured on camera. Perhaps the most interesting innovation, though, is the Henry VI, Part One: Open Rehearsal Project, which offers snapshots of a three-week rehearsal process leading up to a full run-through of the play.

The project offers an interesting hybrid. Open rehearsals are nothing new – companies such as Shakespeare’s Globe have invited members of the public into rehearsal environments ahead of fully staged productions – but what’s key here is the emphasis on access, with people able to attend online from around the world. On this particular day (Thursday 17 June) the numbers didn’t seem enormous – around 23 or so during the first session, 41 at lunchtime – but the idea of being able to tune in and watch actors working in a shared room is appealing, and instantly dynamic, even when they’re just doing a warm-up. The high angle of the main camera takes a literal fly-on-the-wall perspective, and the project sells itself on the privilege of being a voyeur on a privileged process.

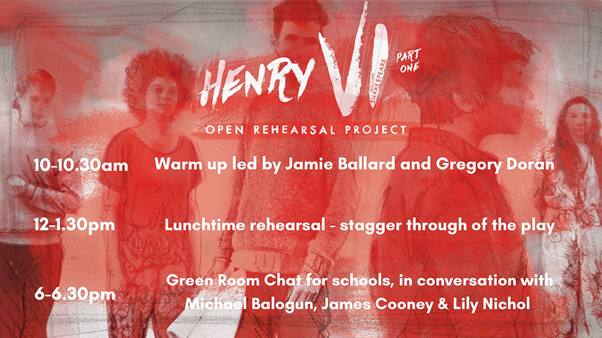

But this is, of course, distinctively different to a ‘normal’ rehearsal process, because the entire project has been conceived around the idea of rehearsal. In many ways, it’s a trailer for what hopefully will be the fully staged version of the Henry VI plays in due course (already compressed to two parts, thus meaning that the Part One being rehearsed here is brief), but the emphasis is on the process itself as the end product, culminating in the full run-through still in the rehearsal room. As such, while the actors are no less brave for being part of a process that is potentially exposing, it’s a carefully curated and organised version of a rehearsal process, with everyone on their best behaviour and a neatly designed programme that includes a a morning warm-up led by one of the actors or creative team; a lunchtime rehearsal for 90 minutes that offers a meatier engagement with sections of the play; and a half-hour 6pm ‘green room chat’ that is a miscellany of reflections, featuring everything from a lecture by Stephen Greenblatt to a Schools Q&A to introductions to various practitioners. It’s a cannily designed introduction to the whole company, inviting investment that will hopefully translate into good audiences for the eventual full production, but also offers a way to begin re-engaging with the idea of returning to the theatre.

The 17 June events began with actor Jamie Ballard leading a physical warm-up that contrasted fascinatingly with movement director Polly Bennett’s work on the previous day. For thirty minutes on Wednesday, Bennett had taken the cast through a series of breathing exercises that made for a wonderfully peaceful viewing experience as the cast spread out in their carefully demarcated two-square-metre boxes to be present in their own bodies. Ballard, on the other hand, took a high energy approach. First it was physical activation through jumping jacks and side-swings for five minutes to music (Depeche Mode?), with an emphasis on getting everyone in sync with one another. Then, after a bit of brief breathing work (lying down and imagining the left arm as a hollow tube that can be breathed through) it was onto vocal warm-ups, with an avowedly non-musical Ballard working to get the company singing a four-part harmony around Jackie Wilson’s ‘(Your Love Keeps Lifting Me) Higher and Higher’. While this was a lot of fun, watching each of the four parts get laid down, the emphasis was again here on unity, with members of the cast mirroring his spatial marking of the note progression. What felt at times like it could be a disaster – I wasn’t convinced by the timing of each layer – ended up in a pretty nice rendition of the song that the company seemed to be enjoying.

The warm-up concluded with director Gregory Doran taking the stand – literally for a moment, as the cast tried to get him to stand on the throne at one edge of the rehearsal room – for a lecture/exercise on rare words in Henry VI, Part One. The exercise was based on some on-brand Bardolatrous assertions about the number of words Shakespeare invented, but the effect of the exercise was more interesting than its etymological underpinnings. Doran read out his self-created ‘alphabet’ of words from 1 Henry VI that are unique, first used, or rare within the canon, getting the company to move around and repeat the words after him, occasionally offering a quick gloss. The idea here was to create a sense of the play’s unique semantic field, to hear and relish the complex words (‘contumeliously’, ‘moody-mad’, ‘warrantise’, ‘perseverant’ being some of the more delicious) as a group. This shifted into discussion of a particularly unusual word – ‘haughty’ – which carries meanings in 1 Henry VI (where the word is used far more than in any other play) of both ‘lofty’ and ‘arrogant’. Frustratingly, this section drew on the actors playing characters such as Mortimer and Burgundy who speak the word, but with only Doran miked up, the livestream rather emphasised the authority of the director rather than the collaborative contributions of the actors. The session ended with Doran inviting the company to give the words spoken in this list the extra weight of being ‘chosen’ – less persuasively, them being chosen by Shakespeare, but more persuasively the idea of the character coining them in the moment to create the effect they seek.

The lunchtime rehearsal took the form of a stagger through of most of Act One of the cut-down version of 1 Henry VI, setting up the play’s core dynamics and inciting events. The sound levels continued to be a bit of a problem here; as Bennett and Associate Director Owen Horsley worked to choreograph the opening entrances, Bennett was nearly inaudible while Horsley’s voice boomed through the speakers. The actors were generally well-miked while performing, while in-between scenes the effect was of a football match, as clusters of directors and actors gathered to talk quietly about specific issues within the scene, the microphone catching murmurs that it wasn’t always clear whether we were meant to hear or not. More so than during the warm-up, there was a nice sense during this rehearsal of the company really working and not necessarily thinking about the online audience, enhancing the sense of a privileged insight into a normally exclusive space.

The bulk of the time was spent on 1.1, underscored throughout by the company musicians, who switched from an evocation of medieval music during the initial invocations of the lords to a more bass-heavy electric rhythm as the messengers reporting losses in France began arriving. This opening sequence also tantalisingly suggested how far the camera set-up for the full run-through has already been established, with some excellent use of high and low POV angles when messengers appeared on the rehearsal room’s balcony, and an intuitive combination of wide and close shots to navigate between the broader scope of the play’s politics and the more personal squabbles.

Rehearsal interventions at this stage – with the cast largely off-book apart from the occasional shout for a prompt, and the action fairly fully choreographed – were about precision. It’s here that Doran’s careful interest in the text came to the fore, as he helped Christopher Middleton see that Gloucester’s first speech picks up on Bedford’s earlier use of the word ‘brandish’, suggesting a continual upping of the ante throughout these early assertions of values and fealty. This set in train the continual escalation throughout the scene, the stakes getting higher and higher, with Mariah Gale’s Bedford, Amanda Harris’s Exeter and Middleton’s Gloucester surrounding Henry V’s coffin and at the centre of verbal assaults from outside. The increased freneticism of the music was key to shifting the tone throughout, all of which led to a point. Perhaps the most important innovation we witnessed here was the reworking of the exits at the end of the scene. At the outset, Bedford, Gloucester and Exeter all took their exits separately which, as Doran noted, left Exeter with no-one to address his final line to. Instead, Doran asked Harris to place stress on ‘Remember, lords, your oaths’, arresting the militant Bedford in his steps and bringing the nobles back together to share their plans for action, before all leaving simultaneously. With a ‘whoosh’, Mark Hadfield’s Winchester was left alone onstage to muse on his own plans.

1.2 to 1.4 – the last interrupted by the lunch bell – were more fully worked out at this stage, though there were still important insights from the rehearsal. The centre-piece of 1.2 was the encounter between Lily Nichol’s Joan and Jamie Wilkes’s Charles, a charismatic young version of the Dauphin, caught in extreme close-up by the camera while hiding to trick Joan. The fight choreography was, by this stage, fairly fully worked out. What the directors worked at here was the specificity of delivery, such as directing Marty Cruikshank’s Reignier to target one of her lines more specifically at Charles, or Horsley asking Nichol to fully commit physically to reaching up to Heaven to draw down her support. These tweaks and clarifications offered the most productive interventions for the viewer; the more complex blocking issues around the fight conflicts in 1.3 and 1.4 – with Horsley trying to help define no-go areas for the actors – were less immediately interpretable.

The 6pm Green Room Chat that closed the day took a very different tone, taking the form of a discussion between five actors designed as a tie-in with the RSC’s partner schools, who were invited to submit questions to the five actors. Here, there was very little specific to 1 Henry VI, with the actors (Nichol, Michael Balogun, Liyah Summers, James Cooney and Anna Leong Brophy) talking about their earliest encounters with Shakespeare and their own challenges. These kinds of events in isolation can sometimes seem superficial, but having these stories emerge towards the end of a three-week rehearsal process that had involved watching the actors both perform and work in their own persons gave this much more weight. Sat in a semi-circle, the five shared honest stories, ranging from Balogun talking about his own homelessness and encountering Shakespeare for the first time in a Crisis workshop on Macbeth, to Cooney complaining about being turned off by Shakespeare when being taught it in static, assessment-focused educational settings.

The value of this event for the RSC brand was clear, with the actors on-message in talking about their struggles with text and the difficulty of studying, instead really discovering the plays once they did them; the legacy of the RSC’s (inadvertently ableist in its framing) ‘Stand Up for Shakespeare’ project clear in the emphasis on learning through performance and through personal experience. What was perhaps most fascinating, though, was the actors’ emphasis on accessibility, on saying that you don’t need to start from a place of understanding caesuras and verse speaking and sixteenth-century language in order to be able to inhabit characters; while at the same time, the rehearsal footage from lunchtime had focused so much on precise and specific application of language. The RSC perhaps finds itself in a complex bind here, of on the one hand celebrating the text-based, relatively scholarly approach to Shakespeare favoured at the RSC (and especially in Doran’s work), and on the other hand working to break down the perceived and real barriers that this focus might create. Having five of the younger cast members in this session even partly framed this as a generational divide, the actors joking that fellow cast member Amanda Harris had been able to play Juliet in her first season at the RSC while they’ve had to work their way through minor roles. One of the actors (I think Balogun) at one point noted that it would be nice to have the easy, seemingly natural, facility with early modern dramatic language that more experienced cast members had; but the emphasis here was that this can be learned in doing Shakespeare, rather than being a prerequisite for being allowed to do Shakespeare.

As the discussion went on, more rehearsal room insights emerged. Nichol described her own difficulty in learning to be still, relating a discussion with Horsley where he had asked her to imagine Joan coming in and rooting herself firmly in a space. Leong Brophy reflected on an unseen bit of the day’s rehearsals where she’d been invited to ‘lad up’ as a soldier during the scene where Talbot is summoned, discovering in that process something of the fast-thinking, ‘front-footed’ military mindset that might help explain Burgundy’s impulsive decision to defect. And in Summers’s discussion of the Bastard of Orleans, a character who spends a lot of time onstage not speaking, the company explored the idea of what it means to be a minor character who is still responding to what is happening, working through Summers’s thought processes around what might drive that absence of scripted action.

Cooney’s closing note – that Shakespeare ‘isn’t written for academics’ – disappointingly kept live the scholarly/theatrical binary that resurfaces so dispiritingly at moments of cultural and creative tension (the end of Emma Rice’s tenure at the Globe perhaps most prominently), but what emerged most powerfully from this discussion for the target schools audience was the emphasis on personal, emotional responses from people who don’t consider themselves experts, offering an entry point for audiences engaging with the company’s approach to 1 Henry VI. As a summing up of the day’s footage, it emphasised what the whole project appears to be about, which is the cultivation of mass engagement with Shakespeare, stressing the work that goes into interpreting and staging the plays over any assumptions of an innate way of ‘doing’ Shakespeare or of prior knowledge. And in carefully curating its audience’s relationship with the company, the RSC is setting up a potentially fascinating final run-through with an audience who, if they’ve stuck with the rehearsals, may be the most prepped audience that 1 Henry VI has ever had.

No comments yet, fill out a comment to be the first

Leave a Reply